Project death

Death used to be a taboo of modern times. Today it’s a very public, permanent guest and a pending topic in our personal life plans.

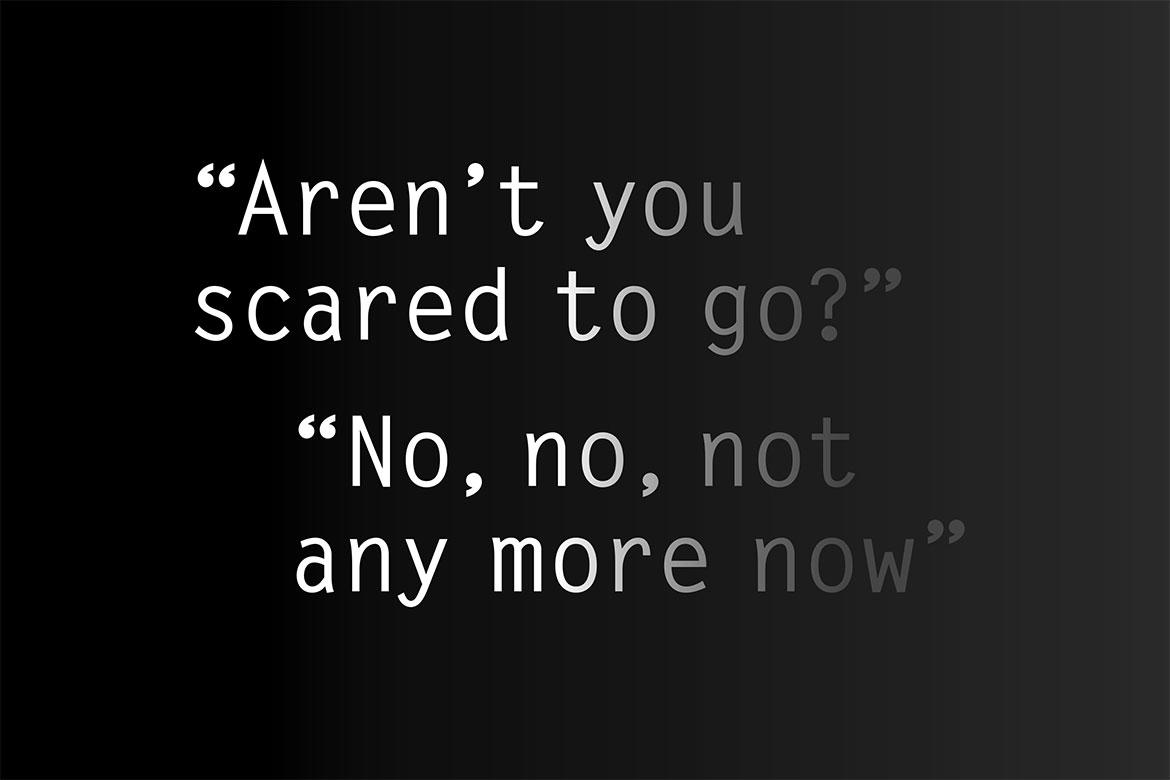

Reminiscences of a 65-year-old ALS patient about the death of her mother, who had dementia. Taken from interviews in the research project "The wish to die in persons with serious illness" by palliative care doctor Heike Gudat.

Everyone has to die. But whether we’re able to do it properly seems to be another matter altogether. ‘Dying and learning to die’, ‘The ability to die’ – so common today are book titles like these, they could easily fill half a bookshop. Then there is: ‘Dying for beginners’, ‘Training manual for accepting the inevitable’, and ‘Travel guide for your last journey’.

Such how-to books tell you about making a living will and about liquidating your home and possessions – things we’re told we should organise in advance, as it’s ‘better late than never’. They even offer ‘checklists for saying goodbye’. But they also explain dying itself – ‘what we can do to achieve a good death’, and ‘how we can overcome our fear of dying’. Apparently, ‘fear’ is a blockage that ‘prevents us from letting go’. We might all want to live a life that’s ‘organised, well thought-through and doubly insured’, but are we ‘equally well-prepared for our transience?’

It’s obvious: death is very much on the agenda. It has now become an object of lifestyle planning. The Augsburg sociologist Werner Schneider has diagnosed a “fundamental transformation” in how society deals with death. The transition to the 21st century, he says, brought about “an increasingly discursive process” about death. It’s now a growing topic of public discussion.

An unforeseen comeback

This is unexpected. Until recently, one of the characteristics of Western modernity has been its avoidance of the topic of death. In the course of the 20th century, death was ‘expatriated’, writes the French historian Philippe Ariès in his ‘History of death’. Death was more and more often relocated from the home to the hospital, and left to the doctors. It did not just lose its ecclesiastical context, but also its public value. It became an invisible, even ‘secret’ event.

The ethnologist and sociologist Bernard Crettaz from the canton of Valais has spent half his career researching into death. When he looks back today, he believes that a “marginalisation” of dying took place, primarily in the years after the end of the Second World War in the era of the consumer society and the post-War economic miracle. It was especially the dead body that disappeared from view, writes Crettaz: “It was disposed of as quickly as possible”.

However, already in the late 20th century, Ariès noticed that something might be changing in our relationship with dying – such as among the psychologists who were criticising the suppression of public mourning. Today, what he presaged has become a certainty: “The changes are dramatic”, writes the sociologist Hubert Knoblauch from Berlin, who has detected an “increasing popularity of death”. Knoblauch believes that this development began in the social movements that made dying into an increasingly public topic from the late 1960s onwards: from the ‘death awareness’ and ‘natural death’ movements via the Aids phenomenon to palliative care and the hospice movement.

Today, the ‘presence of death’ is evident not just in the frequent debates about assisted dying, palliative medicine or brain death, but in the midst of our daily culture. There is an expansion of the ways we commemorate the dead, a new diversity of burial forms, a growing body of ‘self-help’ literature, and even a foray into the TV series we watch of an evening – from ‘Six Feet Under’ and ‘Bones’ in America to the Swiss-German series ‘Der Bestatter’ (‘The Undertaker’).

Entertaining death

The era of repressing death and dying seems to be over. And Knoblauch isn’t the only researcher to have reached this conclusion. The cultural philosopher Thomas Macho speaks of a ‘new visibility of death’, while the sociologist Klaus Feldmann writes of its ‘return’: dying might have been exiled from the everyday lives of most people, he says, but it’s coming back to visit them via the media.

One example is the death of the English dental assistant Jade Goody. First she converted her life into reality TV as an inhabitant of the ‘Big Brother’ house, and then she did something similar with her death. She was 27 years old when she was diagnosed with cervical cancer – and millions watched live as she got her diagnosis. Afterwards, she let everyone watch how her hair fell out and how she became weaker and weaker. Whether on TV or on the title pages of the newspapers, everyone saw ‘the oxygen mask over her agonised face’ (in the words of the German newspaper ‘Die Zeit’), the kisses from her husband, her fear of the end, her tears, her worries about her two sons and her pleading for the ‘death pill’. She even sold her dying breaths to the pay-TV station ‘Living TV’ – but ultimately, Jane Goody died in private after all, in the early hours of 22 September 2009.

Conversely, dying can today make complete unknowns into public figures – such as Norma Bauerschmidt from the USA. She was diagnosed with cancer at the age of 90. But she refused to start any treatment, instead going on the ‘journey of her life’ (in the words of ‘Spiegel’ magazine) across the whole of the USA, accompanied in her mobile home by her son and daughter-in-law. Facebook let the world follow her by reading her everyday diary as she was dying – under posts ntitled ‘Driving Miss Norma’ – and the longer she was on her travels, the better known she became through the press and TV. Her life came to an end one year, 15,000 miles and 450,000 Facebook ‘fans’ later. When her condition made it impossible for her to continue travelling, she moved into a hospice for the dying on the Pacific Coast, where she passed away in autumn 2016.

Individualised farewells

Jade Goody and Norma Bauerschmidt were media phenomena for a media audience. This is also true of the online, live-stream funerals that undertaking companies are now offering mourners in the USA.

This new visibility of death is even more far-reaching, however. Bernard Crettaz has observed how the family and next of kin of the dying have begun taking on tasks previously assigned to experts in the medical, therapeutic and social fields: “To a certain extent, death is being retrieved from the technocratic sphere and is moving more into people’s everyday lives”. One example is the funeral supper, which has been regaining importance in recent years as an event where relatives, friends and acquaintances become a community, offering comfort amidst the mourning. As Crettaz points out, death is also “an exceptional moment of social bonding”.

Undertakers are also acknowledging this fact. They have noticed that there is an increasing desire among the bereaved to take on tasks themselves – such as the design of the coffin and the urn, the speeches at the funeral or even the administrative formalities. Nor is this merely for reasons of economy, as it also signifies a return of personal engagement. “The next of kin want to become active again. Today, they’re making more and more requests concerning the actual funeral”, says Crettaz. “Many undertakers today allow them to participate in rituals, even with regard to the body of the deceased. The next of kin are being allowed to wash them, comb their hair and dress them”. This is surprising, as in modern times we have traditionally focussed our fear of contact on the corpse itself. “But there has been a reawakening of awareness that the body is an important part of the whole theatre of death”.

Live and let die

So, after having been sent into exile, death is returning once again to our everyday lives. We used to be happy to delegate things to functionaries. But today, the notion of self-determination has even reached the dying process. Our epochal urge to individualisation is now getting to grips with dying. But the consequences are just as ambivalent as they are with any other such trend in our times. As always, self-determination also means self-commitment. And this applies just as much to those who are dying.

Werner Schneider has been investigating the current debates about living wills and organ donations. He sees a “new normal” in how death is dealt with, according to which “we are now supposed to plan, organise and manage our own dying”. Death has become a project in life. The current ‘guidebooks’ also advocate for this, measuring up the various options for dying from ‘success’ to ‘failure’. “When will I die, and how? How can I make things easier for my next of kin? What do I do with the ‘treasures’ I’ve acquired in life? Will people be allowed to laugh?” These are all questions that must be answered, according to a recent book by a psychotherapist and chairman of a hospice association. Whoever wants to achieve “a relaxed, anxiety-free Approach to dying” today needs “a clear concept and a conscious attitude” towards death.

Schneider sees here a new kind of “comulsion to attain a socially acceptable degree of concern for the last things”. He believes that society is “monopolising” and “remoralising” the process of dying. And he also feels that we must question these new norms. “Does everyone really have to want to decide whether brain death is ‘dead enough’ for us to be assigned for organ donation? Does everyone have to want to prevent their relatives from making decisions? Does everyone have to want to spare doctors and society from any unpleasantness? Who could here claim to be a truly autonomous subject if he isn’t allowed to change his mind about things – including the ‘last things’?”

Fate is out of fashion

When it comes to the crunch, these questions become ever more pressing. “Death used to be a byword for a fate beyond one’s control”, writes Heinz Rüegger, an ethicist and theologian from Zurich. Today, thanks to our longer life-expectancy and the possibilities of modern medicine, death has instead become a matter of decision-making processes.

According to Rüegger, it’s part and parcel of the “dignity of every human being” to be able to organise both our life and our life’s end according to our own wishes. But at the same time, Rüegger shares Schneider’s concerns. We might want to experience the swiftest possible, pain-free death, in a state of mental clarity and in full control of our physical and social responsibilities, independent of the care of others. But, Rüegger believes, this runs the risk of our becoming beholden to ‘societal pressure’ that turns the question of a ‘dignified’ death into an act of individual, personal responsibility, something that we owe to our relatives and to society in general. The current idealisation of self-determination on our deathbed thus has a downside. “It means that what was intended as an act of liberation instead becomes a new compulsion – one that can demand too much of individuals and in fact denies them their dignity when they don’t succeed in achieving a ‘good’ death”. In other words: our progressive society is on the verge of expanding how we evaluate our sense of fulfilment in life. And this opens up to us the possibility of ‘failure’, right to the very end.

Daniel Di Falco is a historian and a journalist for the ‘Bund’ in Bern.