The most personal decision of all

The sophistication of today’s medicine means that when and how we die is no longer left to fate alone. It is also a consequence of our own decisions – but we rarely take them consciously.

97-year old patient, suffering from polymorbidity and frailty in old age

It took thirteen days for Terri Schiavo to die after the doctors took out her feeding tube. For fifteen years, this 41-year-old woman from Florida had lain in a vegetative state after cardiac arrest and brain damage. Her death in late March 2005 was preceded by a bitter dispute. Her husband wanted to let her die, but her parents fought for her to be kept alive. Both sides claimed they were acting in her best interests. The Schiavo case went through the US courts, was debated by politicians, and attained considerable worldwide attention. It is regarded today as a tragic example of the complexity that such situations can take on – especially when the person actually affected cannot express an opinion.

However much we profit from the successes of modern medicine, many people refuse the option of being kept alive, because they don’t want “to be hooked up to tubes or machines”. No one can know in advance how it feels to be in a coma or to have dementia. But people wouldn’t like to be kept alive at any price.

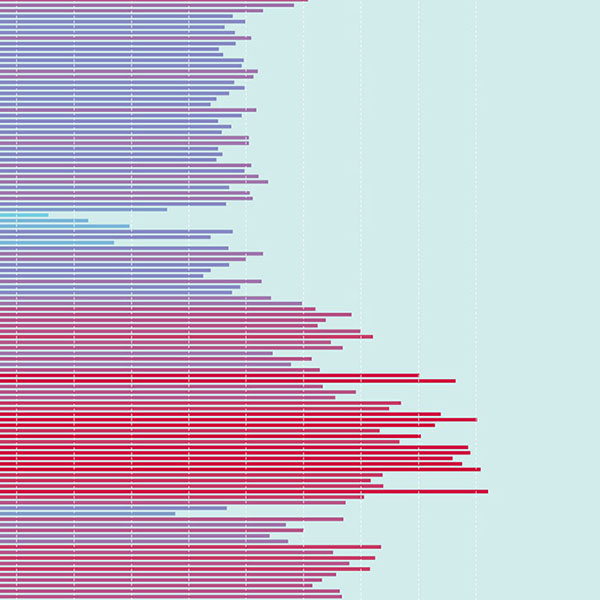

It is common in Switzerland for end-of-life medical decisions to be made that might possibly (or even probably) accelerate the inevitable. And such decisions are becoming increasingly common, as has been shown in a study conducted by the universities of Zurich and Geneva. In cases registered in German-speaking Switzerland in 2013 where death was not unexpected, 80 percent of the deceased had taken advance decisions about the end of their lives. In the great majority of cases, treatment was either discontinued, was not begun at all, or more drugs were administered to alleviate pain and other symptoms. In a small number of cases, the people concerned died by means of assisted suicide. This representative data comes from a survey of doctors.

Let’s put an end to paternalism

But it’s we ourselves who decide about the last things. Patient autonomy has become a core legal and medical/ethical principle in recent decades. It has equivalence with a doctor’s duty of care. Our previously paternalistic relationship with medical professionals – along the lines of ‘doctor knows best’ – has purportedly given way to an interaction between equals. After the doctor has given his or her findings, the patient agrees to a particular treatment – or not. Informed consent is what the experts call it.

The Swiss Act on the Protection of Adults, which entered into force in 2013, strengthens the law on the right to self-determination. For the first-ever time, the patient decree, or ‘living will’, was established on a national basis. This allows a person to determine what medical measures they wish to accept or reject when they are no longer able to express themselves. It is binding for the doctor. Even if no such patient decree exists, the doctor may not simply take a decision on his own. He has to consult the next of kin too. But not even their views are binding – it’s the presumed wishes of the patient that are paramount.

Studies carried out by the universities of Lucerne and Zurich show, however, that problems are now arising in daily healthcare practice. Regina Aebi-Müller, a professor of private and comparative law at the University of Lucerne, speaks plainly about this: “The patient decree, which attained legal certainty in the Act on the Protection of Adults, is practically useless in its present form”. The researchers of Lucerne and Zurich carried out interviews with doctors and qualified nursing staff to ascertain how decisions about ceasing treatment or refusing it are actually made. It transpires that only a few people have made a patient decree. And when an acute situation actually arises, the decree is often neither available nor up to date. In such situations, it remains unclear whether the patient who is dying in an intensive care unit actually wants to be reanimated, or whether the nursing home resident suffering from advanced dementia should be transferred back to hospital and given antibiotics to treat pneumonia.

When you said ‘no tubes’ ...

Doctors are also confronted with patient decisions that are contradictory or impossible to respect. This does not surprise Aebi-Müller, who is studying the legal aspects of patient autonomy within the framework of National Research Programme 67 ‘End of life’: “There are several templates for patient decrees. You can download them from the Internet, and tick the boxes in private”. Patient decrees have to be interpreted, but lawyers are better equipped than medical experts to interpret texts. Aebi-Müller gives an example of where this can end up: a patient suffering from terminal cancer had decreed that she wanted ‘no tubes’. The woman in question later lost consciousness, was unable to empty her bladder, and was visibly suffering. But the nursing supervisor refused to give her a catheter on account of her patient decree. The senior consultant, however, doubted whether the patient would have meant to include this kind of ‘tube’. After the nursing staff’s next change of shift, he inserted the catheter himself. The woman died peacefully that same night.

If the next of kin have to make such decisions, they are often overwhelmed, or unable to agree. They don’t know the will of the patient because no one took the initiative to discuss it in the family. This can be a difficult burden for partners, daughters and sons. “One in three people is traumatised by having to make a proxy decision, and doesn’t know if it was what their loved one would have wanted”, says Tanja Krones, Head Physician of the Clinical Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Zurich.

Absent agreements

Despite patient autonomy, doctors still have the power to make decisions. A trend has become discernible over the past ten years in which “patients tend to be drawn more into making decisions at the end of their lives”, says Milo Puhan, a professor of epidemiology and public health at the University of Zurich.

Few doctors act on their own without discussing anything with their patient and their next of kin, or without any recourse to an earlier expression of the patient’s wishes. The study carried out in Zurich and Geneva showed that in just eight percent of cases where a patient was incapable of making a decision, their doctors took decisions for them. In a further twelve percent of cases, the doctor discussed the matter with professional colleagues or with nursing staff. In a further eight percent, the patients were actually able to make decisions themselves, but their doctors still failed to discuss end-of-life issues with them or their next of kin. Puhan sees one possible explanation in it being difficult to predict the course of a disease. “Diagnosing the phase of dying is medically challenging, and requires a lot of experience”. An Australian study has shown that most conversations about medical decisions at the end of life only take place in the last three days before death. According to how a disease develops, the right moment can be missed altogether.

So, research is revealing possible areas of conflict. Aebi-Müller’s conclusion is this: “Medical situations at the end of life cannot be regulated in the manner that the legislators imagine”. She is convinced that any form of “absolute” patient autonomy will not function. More realistic, in her opinion, would be “relational” autonomy. At the end of our lives, when we are particularly vulnerable and suffering from pain, respiratory distress and fear, we are dependent on relationships. Aebi-Müller argues that medical staff should be given greater responsibility to make decisions, though without lapsing into old patterns of doctor-dominance. “There is no decision more personal than that relating to medical measures at the end of a life”. A relationship between doctor and patient that is based on partnership, in which decisions are made together, can help support people in these situations.

Planning with counselling

The Zurich University Hospital is investigating how such support might be given. ‘Advance care planning’ is the name of he concept, meaning structured conversations with patients and their next of kin. Treatment teams trained in communication – doctors, nursing staff, pastoral care workers and social workers – find out in good time about a patient’s wishes for treatment at the end of their life, and also about their personal views. If they become unable to make decisions themselves, what will actually be important to them? What are they afraid of? The Zurich University Hospital offers expert counselling, not just the patient decrees that can be downloaded from the Internet. “People are given evidence-based, decision-making aids”, explains Krones. This means they know the concrete figures: out of 100 people who suffer cardiac arrest in hospital, even with immediate assistance, on average only 17 of them survive. And of these survivors, five to seven of them are later highly dependent on care.

Advance planning offers a better guarantee that a patient’s wishes will be known and feasible, says Krones. This is also a relief to their next of kin. Such planning may also result in drawing up a patient decree, but it doesn’t have to. Krones recommends a modular system that ranges from an emergency plan signed by the doctor to instructions for what to do in a case of a chronic incapacity to make decisions. The latter could come about because of dementia, or after a stroke. “What’s important is to keep checking with the patient. Because people change”. Perhaps someone has been diagnosed with dementia and wants to refuse life-extending measures as soon as she can no longer recognise her relatives. But what happens if her loved ones realise that this patient seems happy despite her limitations, laughing and taking pleasure in small things? “We have to address These questions”, says Krones.

‘Advance care planning’ is not yet widespread in Switzerland. Krones’s research confirms findings made abroad, namely that advance planning both helps to meet people’s wishes better, and alleviates the trauma suffered by their next of kin. It also means that fewer people are taken to hospital or are subjected to invasive treatments such as operations. This concept does not aim to lower costs, but it appears to be a side-effect. All the same, the patients don’t die any sooner.

This is how we are endeavouring to come to terms with death in a professional manner. Nevertheless, it will always remain something of a mystery. In the words of Ralf Jox, a palliative healthcare professional: “Advance care planning will change nothing about the fundamental insecurity that is characteristic of our existence”. But it could help to increase trust.

Susanne Wenger is a freelance journalist in Bern.

All the studies cited here are part of the National Research Programme 67 ‘End of life’ (NRP 67). www.nfp67.ch.