Into the heat

Anthropologist Graham St John studies event cultures and transformational movements. He is currently investigating how the Burning Man movement translates in Europe, having attended the original event in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert five times since 2003.

Images: Graham St John

“Also known as Black Rock City, Burning Man is often misrepresented in the media as a ‘neo-pagan hippy drugfest’. In fact, this annual arts and fire event has developed into a socially and organisationally sophisticated transnational community.

“There are now 65 regional events in 30 countries around the world, officially recognised to be adhering to the principles of the Burning Man Project. Europe, the focus of my research, is the largest region of growth outside North America. ‘Nowhere’ in Zaragoza, Spain, is the longest-running event in Europe, and Israel’s ‘Midburn’ is the fastest growing with more than 10,000 participants in 2017. Smaller events like those operated by the French, the Swiss and the Swedes are also fascinating interpretations of the prototype. My research involves tracking these events, conducting ethnography and interviewing community leaders. As an ethnographer, I try to experience as much as possible and volunteer where I can, for instance at the media liaison department Media Mecca.

“My first encounter with Burning Man was shaped by my ethnographic experience with alternative festivals and outdoor raves in Australia. I felt I knew the territory, but this could not compare with Burning Man, a 360-degree assault on my senses. I was invited to participate in a camp called Low Expectations in 2003, to which I’ve returned each time, and, more recently, to another camp called Blue Elephants. These people are now my family, my tribe. These camps are in the Blue Light District, part of a temporary municipality whose population swelled to 70,000 people in 2016. There are hundreds of similar self-organising camps in Burning Man.

“While there is substantial planning to the event, the experience is immediate and interactive. You can walk a few metres in any direction and encounter something different. Random acts of kindness, gifting and beauty. One moment, someone might approach you with a tray of crispy bacon; next thing you are roller-skating in the desert, or marvelling at a 65-foot-tall cluster of lighthouses.

Experience the event

“Even as a researcher, it is impossible to become completely separated from this phenomenon. I value membership in the community. I also love science. My project has quantitative elements – largely associated with two completed surveys – but is above all qualitative. I approach writing as an art form – maybe a lost art in the social sciences. There is no such thing as pure objectivity. Experience is paramount; I don’t wear a white coat. A degree of distance is necessary in anthropology, and this is assisted by having a critical angle, being self-reflective, and accepting the criticism of colleagues. It’s also obtained by gaining the perspectives of as many varied stakeholders as possible, reading widely, and by developing an adequate coding mechanism for survey and interview data.

“Ours is the first study of this global movement. The project investigates the dynamics of Burning Man’s diasporic expansion and how its Ten Principles are translated and modified in Europe. I gather information in advance about each event I’m researching, plan logistics and line up interview subjects.

Portrait: Michael Urashka

He is a senior researcher in anthropology at the University of Fribourg, working with religion researcher Francois Gauthier. He holds a PhD from Latrobe University in Melbourne and has published eight books on alternative cultures.

“At an event, there is a varied schedule, including large installation burns, volunteer shifts, helping with art projects and meeting lead artists for interviews, for which I carry a recording device. I also take long bike rides or treks onsite, and fall into deep conversations with random strangers. I take most of my notes post-event.

“But there will be many random and unplanned experiences and encounters. Take No-One’s Ark, for instance, a replica of Noah’s Ark, 10 metres tall and 50 metres long. I had no idea about this installation beforehand, it was truly a revelation, encountered randomly as I trekked across Midburn City on my first night there in 2016. I went inside and lay down to an experimental soundbath, complete with crashing waves as if I were aboard a sea-going vessel. I was there again to witness its destruction by fire at the event’s conclusion in which the entire festival population participates.

Images: Graham St John

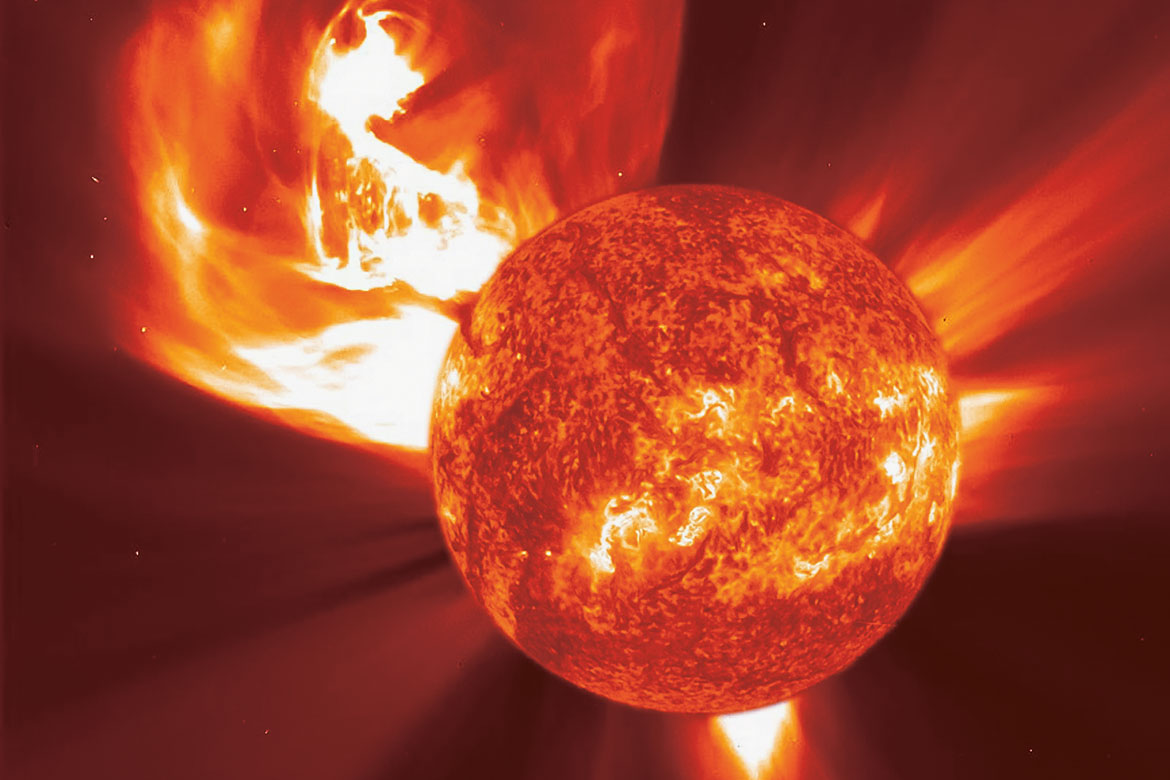

The original Burning Man festival takes place every summer in the Black Rock Desert in Nevada, which becomes a temporary City of art and events for some 70,000 participants. The nature of the festival’s culture and its sculptures like ‘The Temple’ (see above) and ‘El Pulpo Mecanico’ (right) – both from 2016 – make it impossible for anthropologists to keep their distance.

“This phenomenon literally spreads like wildfire, taking hold in far-flung places. In a real sense, the destruction of co-created art by fire is distributing the cultural seeds of this movement”.

As recorded by Clare O’Dea.