Sustainability is a distant dream

The phrase ‘sustainable economy’ ought to be tautological. But it’s not, in part because of problems of comprehension among different scientific disciplines.

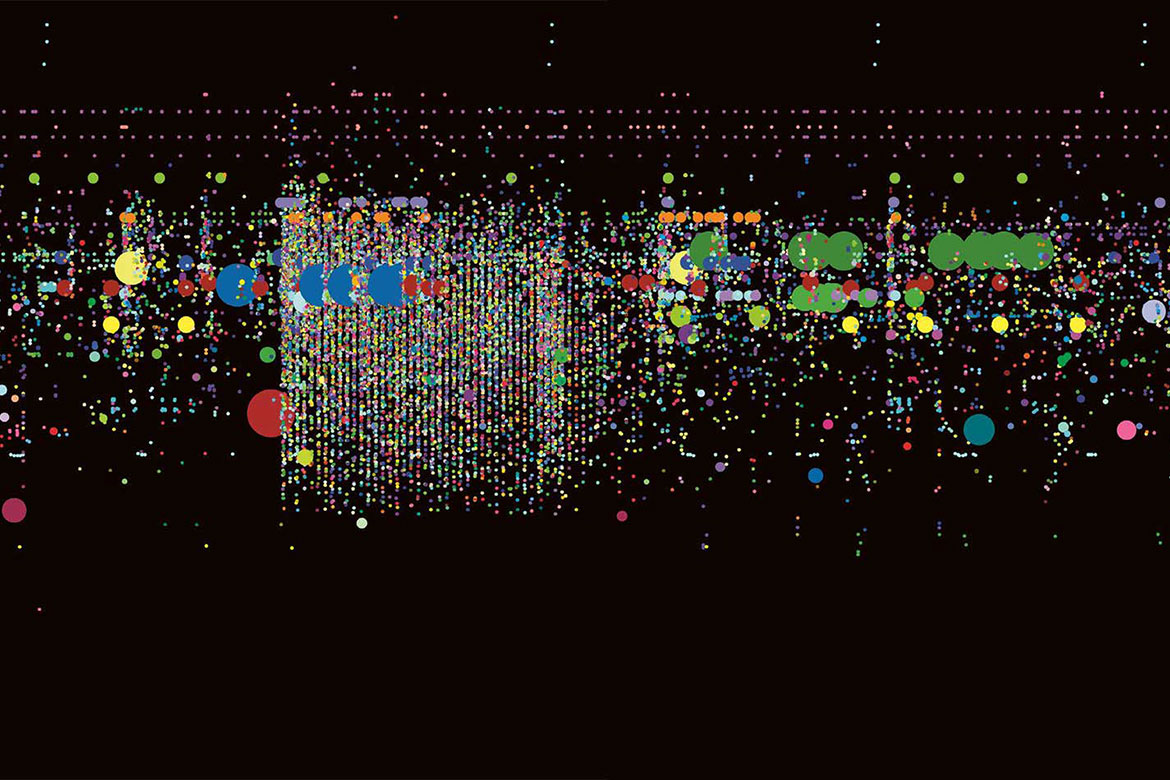

One minute of trading on Nasdaq, 3:35 p.m. on 8 March 2011. The size of the circles shows the number of stocks traded, the vertical axis Shows the rate. The algorithms for high-frequency trading work in microseconds, and were the reason for the ‘flash crash’ of May 2010. | Image: Graphic by Stamen

Our economy is supposed to help us lead a good life. That’s something most scientists and politicians would agree upon. And if, by ‘us’, we mean future generations too, then ‘sustainable economy’ ought to be tautological. If the economy isn’t sustainable, then it defeats its very purpose. After all, ‘economy’ originally meant the art of good housekeeping.

But the phrase ‘sustainable economy’ isn’t tautological at all. In some quarters, the concept of ‘sustainable’ is even an object of scorn. And yet our increasing consumption of resources, the impact of climate change and species extinction are just a few indications of the unsustainability of our present economy. Why is this? And how can we change it? These simple questions open up a host of others. Why do economic operators – from the single-person household to multinational enterprises – act the way they do? Shouldn’t or couldn’t other incentives be set? What statutory regulations would be politically acceptable? How can we promote and finance green technologies? Can the economy both increase prosperity and use less resources? Is a stable, zero-growth economy conceivable? What do we really mean by ‘prosperity’ or ‘good life’? These are all questions being asked today by different sectors of the economy and by different disciplines in the social and technical sciences and the

humanities.

Development is too slow

Gunter Stephan is a professor in economics at the University of Bern, and President of the Steering Committee of the National Research Programme ‘Sustainable Economy’ (NRP 73). He believes that academia finds it difficult to answer these and other interdisciplinary questions because of how it is organised into individual disciplines. In his opinion, research should concentrate on setting different incentives for every aspect of the economy – whether in production, consumption or distribution. And it should investigate how to train the kind of experts that will be needed once we have achieved the goal of a sustainable economy.

We turn next to Stephan’s colleague, Lucas Bretschger of ETH Zurich, who sees further topics that need more research. He is currently the President of the European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists. His vision is of research into the long-term connections between the economy and ecology, taking into account the momentum of each of them and the North-South problem.

Naturally, each field has its own research needs. Joëlle Noailly is the head of research at the Centre for International Environmental Studies in Geneva, and she is looking into the role of innovation. New, ‘clean’ technologies will do more than just reduce the pressure on the environment, she says. They could also create new jobs, while research and development in this sector will bring an especially large surplus of knowledge from which other sectors could also profit. This is because clean technologies could find applications in many areas, including the semiconductor industry and thus in IT. “But development is too slow”, says Noailly. The ‘big players’, namely the big energy corporations, are not very innovative. After all, pollution doesn’t bring costs with it. This is a factor that the market alone cannot correct; we need political regulations instead. But the lack of innovation in certain sectors isn’t merely a result of the regulatory framework: it also comes down to entality. “The impact of regulations has to be studied more intensely. A lot of research is already being carried out, but we now need fine-tuning between the different instruments. According to the textbooks, incentive taxes are the most effective. But in practice, other measures often function better, such as subsidies for ‘clean’ technologies, or bans on ‘dirty’ technologies”.

Helga Weisz is a professor at the Humboldt University in Berlin and at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. She is researching in the field of industrial ecology. There is pretty good research into industrial resource flows on several levels, she says. “However, researchers often only look at energy and greenhouse gases, while other resources and waste products receive little attention. And we know little about the social and cultural framework conditions that determine resource flows”.

Traditionally, industrial ecology considers two approaches: resource efficiency and the recycling economy. The former, says Weisz, can be integrated well in economic models. It’s a darling of politicians because it promises to let us have more and use less at the same time. But there is a danger that increases in efficiency in fact only serve to keep us on the wrong paths for a longer time. The idea of the recycling economy, on the other hand – in which all waste is a raw material for something new – is a plausible vision, but the big, open question among researchers is how it might be incorporated into economic models. “There are numerous good examples for circular production”, says Weisz, “but to what extent can we expand and resize them? We are still lacking a systems analysis for this”.

People as automata

Weisz and Noailly talk about cultural frameworks and mentalities – and these are issues typical of the humanities. But up to now, the humanities have been little involved in economics research. It’s time for that to change, says Christian Arnsperger, an economist and professor of sustainability and economic anthropology at the University of Lausanne. But there is resistance to be overcome. “Many economists don’t want the humanities involved at all. Economists orient themselves traditionally on the natural sciences and want to see the laws of the economy as laws of nature. In order to model economic procedures, they treat their actors largely as automata. They’re interested in what people do, but not in what they think and feel”. Concepts from the humanities – such as fear and estrangement – are foreign to mainstream economists, but they are important, says Arnsperger, if we want to understand what really motivates people, or what in the short-term keeps them from

adopting alternative patterns of behaviour. Is this attitude perhaps even one of the reasons why we lack sustainability in our economy? Arnsperger hesitates to answer this, but then tentatively agrees: “Yes. By blocking these things out, economists are also passively helping to make the economy what it is today”.

The schools are divided

Arnsperger here addresses a factor that is making research into a sustainable economy even more difficult. It’s not just that we need to involve many disciplines that all have their own, different knowledge cultures. Within these disciplines themselves, too – and especially in the field of economics – there are different schools of thought that sometimes offer very different answers to the same questions, according to their respective basic assumptions about the world. These assumptions in turn depend on their own research areas and methodologies. For example, whether people favour tax incentives or subsidies has a lot to do with their ideological preferences.

In broad terms, we could say that the mainstream – the neoclassical economic approach – seeks ways in which economic performance can be uncoupled from environmental consumption. Heterodox schools such as ecological economics, on the other hand, tend to search for alternatives to an economy founded on growth compulsion. These two perspectives are

difficult to reconcile.

Stephan acknowledges these difficulties. “In many ways, the representatives of these two schools of thought simply talk past each other”. But there isn’t even any unanimity about whether these two schools are actually different in the first place. Bretschger says: “The environmental economy has taken up many issues of ecological economics. We’ve never been of the opinion that prosperity can only be judged by the growth rate of a country’s gross domestic product. You only find that kind of thing in old textbooks”. Nevertheless, he does add that many of those politicians responsible for the economy have indeed read those old textbooks. They also have other reasons for wanting growth, and we have to take their opinions seriously. Because in a democracy, you always have to find solutions with majority support.

Bretschger adds something else, too: We’re always open to critical perspectives, but if someone rejects the basic tools of economics, then it’s naturally difficult for them to collaborate with economists”. And yet these ‘basic tools’ are precisely what are being criticised by the other schools in the economic sciences. Weisz is a former member of the executive board of the European Society of Ecological Economics, and she resolutely disagrees with Bretschger’s assessment. She does agree that neoclassical economics has integrated several findings of the ecological economists into its models, as these can no longer simply be ignored. But this has still always been done within the neoclassical paradigm. “This paradigm itself – with its focus on maximising wealth – has remained untouched up to now”.

Growth is therefore the 64-thousand-dollar question when it comes to sustainable economics. And there is an immense need for more research, regardless of how you approach the question. “Some want economic performance uncoupled from resource consumption”, says Weisz, “but they can’t tell you how it should happen. Others criticise economic growth but can’t tell you how we might avoid massive social upheaval if economic output slows down. The key issues remain open on both sides”.

Marcel Hänggi is a freelance science journalist in Zurich.