How justice and science are looking for the truth

Science and justice share the common goal of seeking out facts, but their results often diverge. Whilst there is mutual inspiration between these two parts of society, there are also some basic misunderstandings.

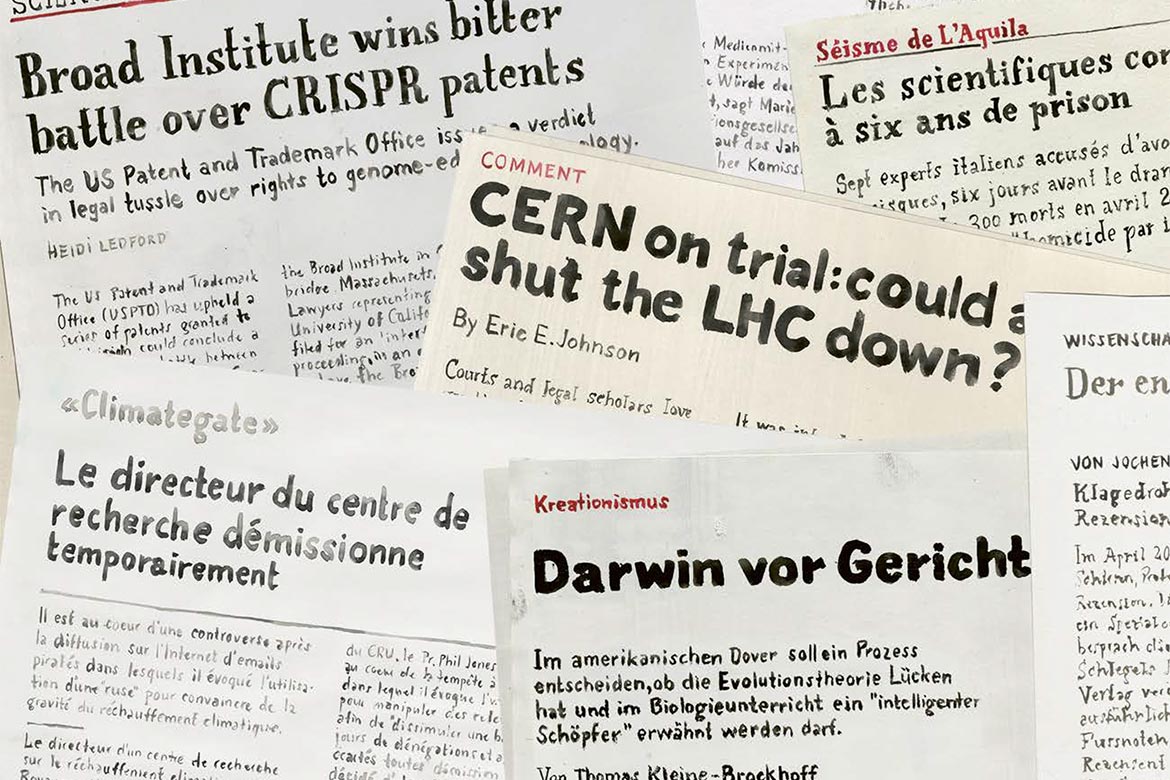

Illustration: Johanna Schaible

One reference in a scientific article can be enough to decide the outcome of a court case. This occurred at a child abuse trial in the Netherlands in the summer of 2017. “The court called upon us as expert witnesses”, says Silke Grabherr, the head of the University Center of Legal Medicine at the University of Lausanne. She took her usual approach to the role and included a review of the scientific literature in her report. “But the defence lawyers”, she continues, “spotted among the references an article whose statistical sample was deemed insufficient. We had mentioned this study purely because it was the very first study on the issue, much in the same way that we would have approached writing a scientific publication. In fact, all the subsequent articles drew the same conclusion. However, the mention of this first study was sufficient for our report to be rejected and therefore affect the trial”.

This episode is symptomatic of the trend whereby experts are questioned with no holds barred. It’s something that has only recently become more frequent on our continent. “Scientists have got used to it over many years in the United States, but in Switzerland and Germany, the in-court testimony of an expert witness, an academic, had always been held to be true”, says Grabherr. Above all, it is an illustration of the complexity of the relationship between science and justice. Both are defined by facts, albeit in different ways.

An overly simplistic vision

At times, it seems the judiciary is set on being seen as even more scientifically exacting than science itself. For Alain Papaux, a philosopher and epistemologist of law at the University of Lausanne, this objective is paradoxical: “It’s a funny situation. Lawyers would like to be able to declare things as if they were scientists and even employ models borrowed from the hard sciences. Unfortunately for them, they are adopting a somewhat Cartesian model of science, which generally speaking is completely out of date. In today’s world, scientists no longer believe in the absolute truth. They simply believe in the consensus of the scientific community. By doing this, what they’re actually doing is returning to the way in which law was practised more than 2,000 years ago”.

All this to-ing and fro-ing is quite strange, particularly when you consider that the courts are increasingly reliant on the tools of science to prove the facts they must judge, such as cerebral imaging and DNA profiling. And it’s even stranger if we consider the much more fundamental but less noticeable change that’s sending scientists on a different journey. “Scientists are happy to say they will look closely at what lawyers are doing”, says Papaux. “Many have affirmed that science is a moral law – these include great epistemologists like Henri Poincaré and Karl Popper, and even hard positivists such as Jean Bricmont and Alan Sokal. Popper affirms that facts in science are established in a similar way to trial by jury in case law. In other words, we find the same intersubjectivity at the heart of science”.

Knowing the limit

At first glance, there is a fundamental difference between the kind of evidence that is offered in judicial proceedings and that issuing from scientific experiments. “Evidence in a trial is subject to a range of rules that do not apply to researchers”, says Olivier Leclerc of the Centre for Critical Legal Studies in Saint-Étienne, France. “There are time limits: factual evidence can be ruled out. In other words, it can be deemed to be too old to be taken into account. In some cases, there are limits on the forms that evidence can take. For example, sometimes only a written document can be used”. According to Papaux, this means a judge can reject expert testimony as being irrelevant in the eyes of the law, even if he is actually convinced of its scientific validity. Some evidence can be considered as factual proof, but still turn out to be unusable. “Take a video of a crime being committed that was obtained illegally: we can say that it reveals the facts beyond any doubt. But that’s too bad: illegally obtained evidence is not proof, and a judge doesn’t have the right to take it into account”.

According to Leclerc, any lawyer who thinks such limitations don’t apply to science is idealising the scientific process. “In science we also subject proof to rules. We have practical and ethical standards and the peer-review process”. In both law and science, the truth is approached not through certainty, but through the convergence of interpretations, through collective choices on the admissibility of processes, and as a result of an enlightened consensus.

Grabherr embodies this way of doing things, and as such stands at the interface of the two domains. He uses the peer-review principle on a daily basis in legal medicine. “Each one of our expert reports is subjected to the scrutiny of a review committee: it’s drafted by at least two people and then reviewed by a team composed of a dozen doctors”, says Grabherr. “Often the reviewers point out that we have gone too far with one interpretation, or that somehow affirmation has not really been shown. This has helped us avoid a good number of mistakes”. This is an advantage of the Swiss system: legal doctors cannot work alone, but must be attached to an institute.

Evaluating experts

From one country to another, there is great variation in the way legal specialists are chosen. In the United States, the Supreme Court entrusts this task to judges, a practice that began with its 1993 trial decision on Daubert v. Merrell Dow. The trial pitted the parents of a child born with a disability against the manufacturer of a medicine for morning sickness. “Since then, it has been down to the judge at hand to evaluate the reliability of expert witnesses – in the main part proposed by the parties – on the basis of whether the knowledge presented as evidence is generally accepted by the relevant scientific community, whether the error rate is known, etc.”, says Leclerc. In France, on the other hand, experts are elected by the judges, but there is no reliability issue, as they are chosen from lists of specialists. These lists are drafted by a meeting of the general assembly of the courts of appeal, using a nomenclature decided by the Ministry of Justice itself. Once they appear on that list, no experts may be brought into question at trial.

This is a big difference. “In the US, one can talk of jurisprudential epistemology”, says Leclerc. “The jurisprudence of the Supreme Court determines what scientific knowledge is admissible in the light of a trial. Switzerland lies somewhere in the middle: in principle, prosecutors are free to designate expert witnesses. But they, in turn, are increasingly turning to legal doctors who can then hire specialists from a particular domain to work with them, says Grabherr.

Truth and justice

There is no established relationship between science and law. In practice, both consider truth to exist only when it is “beyond all reasonable doubt”, not in any absolute form. In fact, it was in law that this means of approaching uncertainty was first accepted, long before the sciences. Science today, however, has no issue in accommodating uncertainty, whereas the law finds itself increasingly drawn toward the positive certainty that it wrongly deems to be offered by science.

There are two recent examples that illustrate this ambivalence clearly. The first is a class-action suit brought by patients who had contracted atherosclerosis following vaccinations against hepatitis B. “France’s Court of Cassation ruled that the epidemiological studies presented failed to show a solid causal link between the vaccination and the illness”, says Leclerc. “In 2008, the Court changed its mind, considering that there was serious, accurate and concordant evidence of a link”. In this case, the judiciary reaffirmed its autonomy with regard to establishing the truth, by using a different standard of proof: here a lower level of certainty was admitted as sufficient at trial.

The second example shows how the opposite can be held as true. A study presented in October 2016 in the journal PeerJ Computer Science described an algorithm that correctly predicted 80% of decisions handed down by the judges of the European Court of Human Rights. Nonetheless, this kind of predictive legal tool threatens the uncertainty to which the law is so attached. For Boris Barraud of the University of Aix-Marseille, who has looked into the study, “this uncertainty is a good thing when it means decisions are adapted to the peculiarities of each case. For example, it’s what allows for clemency in judging the perpetrators of altruistic crimes – particularly whistleblowers – who have acted in the general interest”.

Machine justice – which assumes a single solution based on the jurisprudence and the facts taken as a whole – does not draw the law closer to the scientific method. It actually paints an idealistic picture of the sciences, one which they have long left behind. In Papaux’s view, “for decades epistemologists have been sounding the alarm. Most algorithms are based on statistics, but they only produce coherent results in the field of mathematics. Everywhere else, there are always choices and interpretations to be made. Ignoring this is scientism and not science”. In this sense, the law is chasing the ghost of science, and by so doing it runs the risk of losing its raison d’être. “The truth is only a small part of the law”, says Papaux. “After all, its main aim is to serve justice and not the truth”.

Nic Ulmi is a freelance journalist based in Geneva.