Scientists must get used to it: they will increasingly have to deal with justice

The idea that a historian could be hauled to court by a Holocaust-denier is something we naturally find outrageous. Luckily, the judge in question ruled in the historian’s favour. But what if he had decided differently? Is it right for a British judge to determine what counts as historical truth in the Third Reich? Can it end well, if an arch-conservative federal judge in the USA is allowed to decide on whether evolution may be taught in schools? Or that the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg should have to rule on whether CERN in Geneva might be on the verge of triggering the end of the world? It’s doubtful whether any of our judges have the scientific knowledge needed to decide such complex matters. The US legal scholar Eric E. Johnson doesn’t see any fundamental problem here: “No court should abdicate its role as a bursar of equity, even where […] the factual terrain will be intensely intellectually challenging, and the jurisprudential conundrums are legion”. In other words: researchers themselves are naturally also beholden to the law. Just like science, the judicial system too is a cornerstone of any society. Over the millennia it has found ways of establishing as much justice as possible. It has developed its own, meticulously structured approach, its peculiar protocols and, not least, its approach to hearing expert witnesses – often the opinions of scientific experts. But court proceedings sometimes make the work of researchers difficult. Given the increasing significance of science – and its increasing politicisation – researchers will inevitably find themselves in court more often in future. That’s just something they’ve got to get used to. And if they’re going to avoid being browbeaten into abandoning the same open, discursive culture that is actually essential for establishing the truth, then scientists and scholars are going to have to learn how best to deal with the baffling idiosyncrasies of the judicial system. And they’d better do so as quickly as possible. CC BY-NC-ND

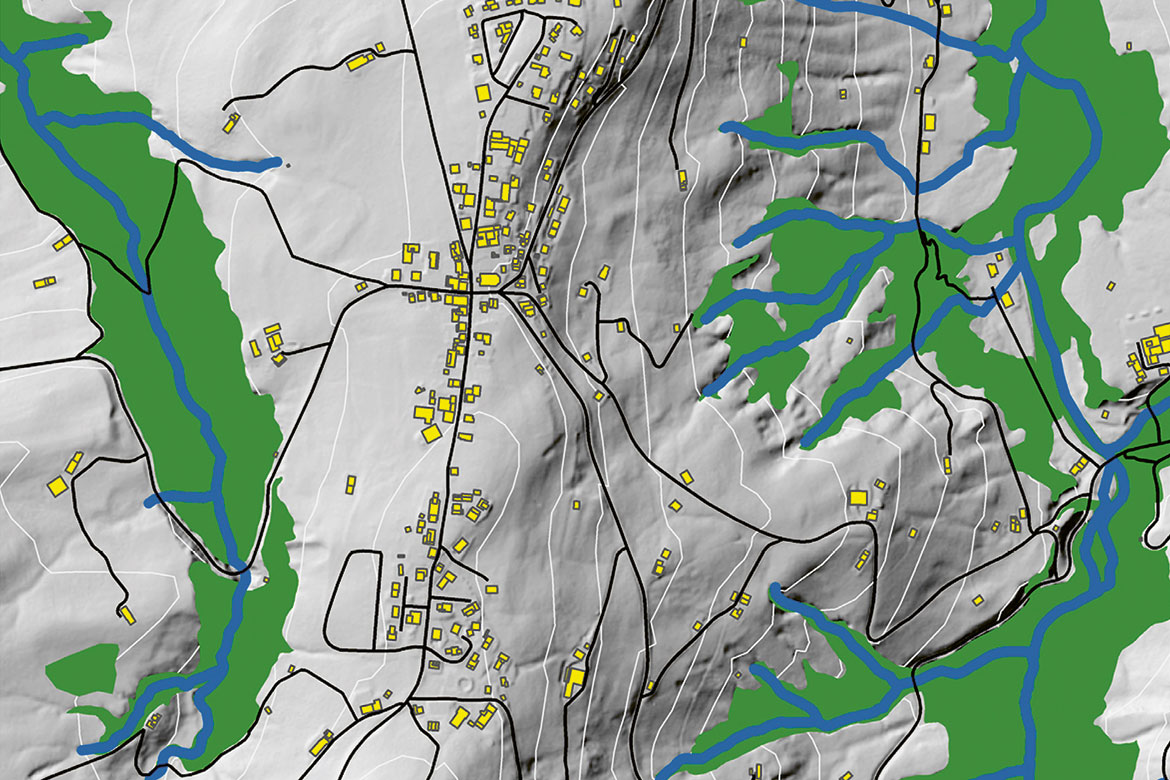

Illustration: Johanna Schaible

The idea that a historian could be hauled to court by a Holocaust-denier is something we naturally find outrageous. Luckily, the judge in question ruled in the historian’s favour. But what if he had decided differently?

Is it right for a British judge to determine what counts as historical truth in the Third Reich? Can it end well, if an arch-conservative federal judge in the USA is allowed to decide on whether evolution may be taught in schools? Or that the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg should have to rule on whether CERN in Geneva might be on the verge of triggering the end of the world? It’s doubtful whether any of our judges have the scientific knowledge needed to decide such complex matters.

The US legal scholar Eric E. Johnson doesn’t see any fundamental problem here: “No court should abdicate its role as a bursar of equity, even where […] the factual terrain will be intensely intellectually challenging, and the jurisprudential conundrums are legion”. In other words: researchers themselves are naturally also beholden to the law.

Just like science, the judicial system too is a cornerstone of any society. Over the millennia it has found ways of establishing as much justice as possible. It has developed its own, meticulously structured approach, its peculiar protocols and, not least, its approach to hearing expert witnesses – often the opinions of scientific experts.

But court proceedings sometimes make the work of researchers difficult. Given the increasing significance of science – and its increasing politicisation – researchers will inevitably find themselves in court more often in future. That’s just something they’ve got to get used to. And if they’re going to avoid being browbeaten into abandoning the same open, discursive culture that is actually essential for establishing the truth, then scientists and scholars are going to have to learn how best to deal with the baffling idiosyncrasies of the judicial system. And they’d better do so as quickly as possible.