How architecture changes indoor temperatures

Climate control doesn’t necessarily mean having air-conditioning. In fact, indoor temperatures are also affected by a building’s architecture.

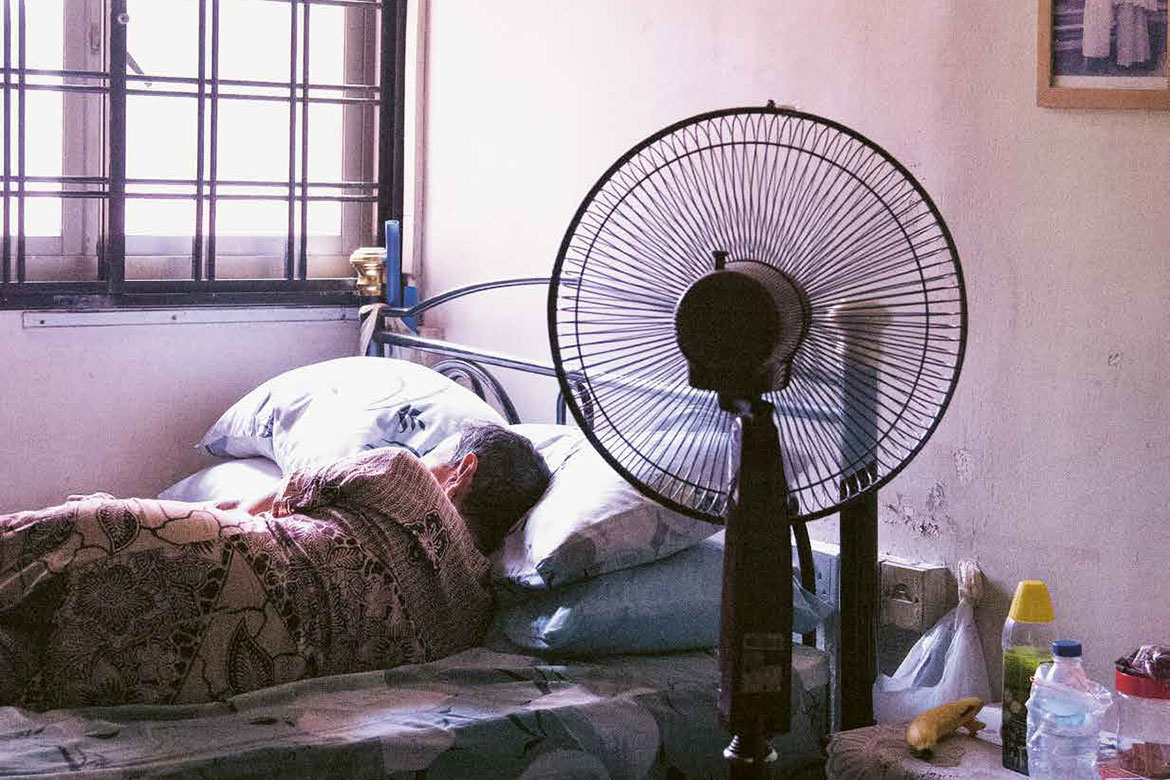

Hot and humid: In this large, modern apartment building in Singapore, the electric fan has replaced traditional ventilation | Photo: Katja Jug

Twenty-two degrees Celsius is a pleasant indoor temperature, and in our era of urbanisation it’s become a global standard. But it means using up an absurd amount of energy. When the climate is hot and humid, we cool our buildings massively; and in the colder seasons, we turn up the heating. The Zurich-based architect Sascha Roesler shakes his head when he thinks about it. “We have to ask radical, critical questions about this specific architectural legacy of the 20th century – namely the idea that the indoor climate of a building has to be thermally separate from the outdoor climate”. Roesler is currently an SNSF Professor of architecture and urbanism at the School of Architecture of the Università della Svizzera italiana (USI) in Mendrisio. His aim is to find construction methods that exist in a state of exchange with the environment. Because “in previous centuries, these transitions were fluid”.

Up to now, researchers have mostly analysed individual buildings. “But with the march of urbanisation being global, we urgently need to pay greater attention to large, urban constellations and their microclimates. Because cities are man-made, their microclimates are also always a result of the architecture”, says Roesler. He sees climate control as a cultural practice and is investigating what passive forms of ventilation have been preserved in three complex megacities: Cairo, Santiago de Chile and Chongqing. He wants his findings to help determine thermal concepts for our architecture of the future. Roesler here invokes the Indian historian Dipesh Chakrabarty, who believes that the history of climate cannot be written without considering man as a ‘geological actor’. Chakrabarty is a leading theoretician of post-colonialism and is convinced that the cultural sciences and the humanities ought to be engaging with the topic of climate change.

The impact of the climate on architecture and on the wellbeing of people in big cities is something that already occupied Roesler when he worked at the Future Cities Laboratory of ETH Zurich in Singapore. He spent three years there, investigating forms of ventilation in mass housing schemes in South-East Asia. He focussed on the financial metropolis of Singapore and the Indonesian plantation city of Medan. It’s hot and humid in both places, and the climate is determined by the monsoons and the cycle of the rainy season. Both places also have a long tradition of ventilating buildings naturally. This tradition resulted in a typical type of filigree architecture with high ceilings so that the air can rise up. Building with wood ensures permeability to air, while outreaching roofs protect the buildings from rain and provide shade for the façades. The residents know the art of cross-ventilation. However, Roesler has found that this natural form of ventilation is losing its relevance. It was still in use in mass housing schemes in Singapore until the 1990s, but here, too, the air-conditioner has entered into widespread use. Young people in particular like the comfort provided by AC, and Roesler believes that they’ve forgotten how natural ventilation methods function. Those methods meant keeping doors open, and that in turn reduces your private space.

Living without a fan is not impossible

In the poorer plantation city of Medan in Indonesia, Roesler has observed how a belief in modernity and a desire for Western standards has displaced climate-adjusted construction. This has fatal consequences for poor members of the population who can’t afford an air-conditioner. Instead of constructing apartment buildings in a traditional manner that is permeable to air, they’re now building with bricks. The result is closed-off rooms with low ceilings. “It’s so hot and humid in these houses that people sometimes don’t even sleep at home any more at night, but outside in the open”, says Roesler. Those who can afford it solve their problem by buying a fan or an AC unit.

Roesler is convinced that modern architecture must begin to combine active and passive forms of climate control – in other words, mechanical air-conditioners and natural forms of ventilation. “We should avoid fitting out buildings with air-conditioning after the fact if they were originally intended for natural ventilation”, insists Roesler. “We have to rethink the topic of climate-control in architecture, and do so in terms of observing microclimates”. He is convinced that the interviews, films and building analyses by his doctoral students (see box) can make an important contribution to promoting the debate about climate-control. He points out that his findings cannot be transferred directly to the Swiss building scene. But he has two other primary goals in his research: first, he wants “architects to start engaging with climate issues intensively once again when they design buildings”. And secondly, he would like a larger field of activity to emerge in the architectural sector in which “there’s a broad spectrum of possibilities for architecture to react to climate relationships”.

- The Chinese city of Chongqing is growing at breakneck speed and currently has 32 million inhabitants. Its winters are getting ever colder, but its apartment buildings are not insulated and have no central heating. Here, Madlen Kobi is investigating what thermal strategies the inhabitants are developing.

- In Santiago de Chile, where people mostly own their own apartments, Lionel Epiney wants to find out how global thermal norms are influencing housing construction – such as with the British label BREEAM, an assessment system for ecological and socio-cultural sustainability in buildings.

- In Cairo, the oldest big city of all, Dalila Ghodbane is looking at how poorer sectors of the population are changing their structural heritage on account of their need for a comfortable climate in their homes.

Karin Salm is a freelance culture journalist in Winterthur.