Too much food in hospital can lead to complications

Nutrition therapy is one of the most frequent interventions we find in everyday hospital life. Often it’s not possible to know in advance if it will help. Sometimes it might even be detrimental.

The hospital kitchen is an important factor in the health of patients. The effect of nutrition therapy is being tested in a study. Image: Keystone/Gaetan Bally

In order to aid their recovery, many patients in hospital are fed a diet that is particularly rich in energy and proteins. But recent studies of patients in intensive care have shown that the effect of this is sometimes the exact opposite of what is desired: too much food in the acute phase of an illness can slow down the healing process and lead to complications.

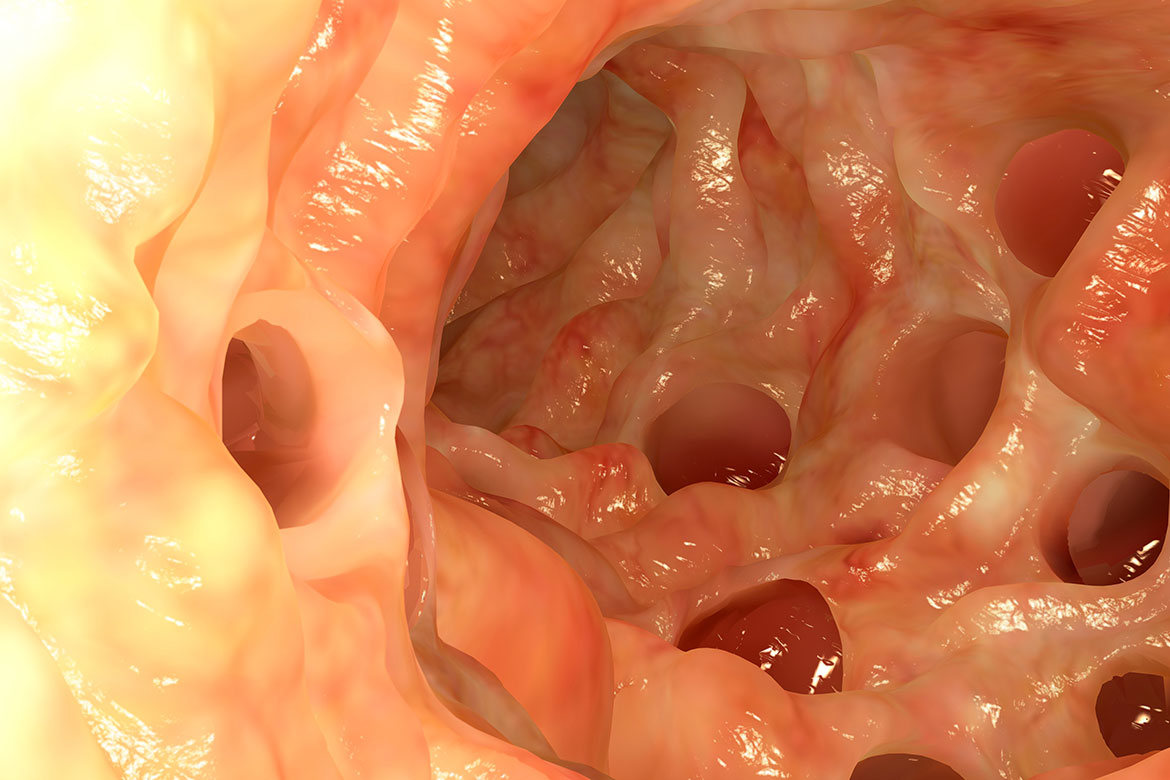

We still know little about the reasons for these negative effects. One possible cause, doctors think, is that a high energy intake can disturb natural healing processes. These include breaking down injurious substances and micro-organisms within cells – so-called autophagy. A nutrient deficiency can provide extra stimulation for this process. That would explain why people and animals react to many illnesses by losing their appetite.

“It seems plausible that increased food intake does not always help even acutely ill patients in the general wards. In the worst cases, it could even harm them”, says Philipp Schütz, the senior physician for endocrinology, diabetology, clinical nutrition and internal medicine at the Aarau Cantonal Hospital. But nutrition therapies are among the most frequent interventions in everyday hospital life, because roughly a third of all patients are at risk of malnutrition. This in turn can cause higher mortality and complication rates, especially in the case of the chronically ill, where long-term malnutrition can impair the immune system and thus also its ability to respond to acute diseases.

This is why Laurence Genton, President of the Swiss Society for Clinical Nutrition, emphasises that the positive aspects of using targeted nutrition therapies in hospital by far outweigh the negative. “However, there is as yet no solid data about their efficacy in multimorbidity – in other words, where patients have several illnesses at once”.

It is precisely this patient group that is growing today on account of increasing life expectancy. It is among them, too, that Schütz is investigating the usefulness of nutrition therapies. For his first prospective study he recruited 2,000 malnourished, multimorbid patients in the general wards of eight Swiss hospitals. He divided them up into two random groups. One group was given a nutrition therapy, while the other ate according to their individual appetites, according to what the hospital kitchen had on offer. Schütz’s team is examining whether the screening procedure used can reliably identify those patients in whom a nutrition therapy has achieved its primary goal – in other words, those who now have an adequate supply of calories, proteins and micronutrients and are thus also experiencing an increase in muscle tissue.

Personalised nutrition therapy is the goal

Initial results have shown that the screening process functions, and the nutrition therapy has a positive impact on weight level. But the really interesting question is one that Schütz will only be able to answer after having evaluated all the data next year, namely: “How does this affect the acute illness for which the patients came to hospital in the first place?”. Furthermore, Schütz is hoping to establish principles to enable him to make prognoses about who will profit from a therapy, and who won’t. To this end, the researchers are investigating specific markers in the blood and the genes of all the participants. They then link these markers with the data on the progression of the disease. Their goal is to find clues that could serve as the basis of personalised nutrition therapies.

Genton is also hoping to get data that will both prove the usefulness of nutrition therapies in the healing process, and show when these therapies have an impact. “Then we’d have strong arguments to take to the political decision-makers and the insurance companies, as we could prove that nutrition too is a part of a patient’s medical treatment”. Even Hippocrates was already of this opinion when he advised: “Let food be your medicine and medicine your food”.

Stéphane Praz is a freelance science Journalist.