Controversy: do new technologies put pressure on people with disabilities?

Intelligent prostheses, exoskeletons, smartphones: ever smarter technological advances are supporting the disabled. But are researchers focussing too one-sidedly on their disabilities?

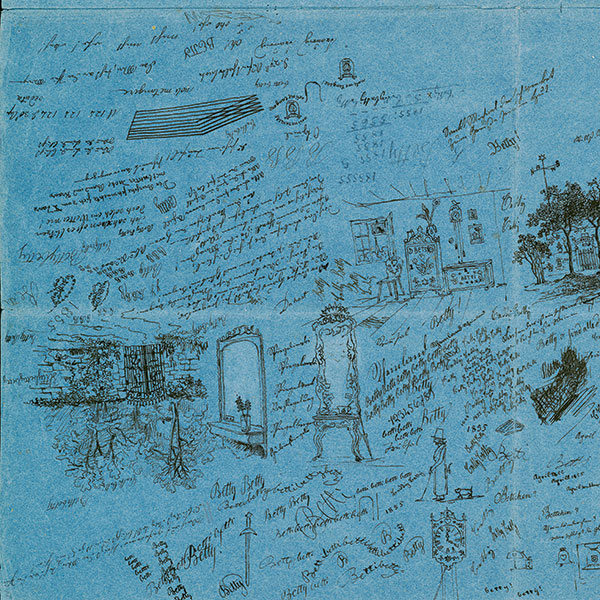

Image: Valérie Chételat

Disabilities were for a long time regarded primarily as individual limitations. Society developed correspondingly individual solutions. Inasmuch as possible, the person in question was made ‘whole’ again – by means of physiotherapy, prostheses or rehabilitation. And they were given a disability pension.

It was only in the 1980s that our perspective on disability began to change. Today, we see ‘disability’ as signifying the interrelation between individual impairments and the barriers in the environment that impede people’s participation in society. Such a perspective promotes equal status for people with disabilities, because it places the focus on the barriers around them. If these barriers disappear, then their disability also ‘disappears’.

It’s just the same with the notion of the ‘flaws’ that often go hand in hand with a disability. The Swiss philosopher Peter Bieri defines these as characteristics that are unwelcome in society and thus have to be hidden. If society doesn’t censure such things, then there is no flaw at all.

But what do these issues have to do with new technologies? Technological research today is primarily focused on making individuals ‘whole’ again. The ETH Cybathlon in Zurich, for example, which is a competition between disabled people with technological support, was originally focussed one-sidedly on this aspect.

I think it is also very important to look for technological solutions that reduce the obstacles in our environment. We need technological progress on an individual and a societal plane. Incidentally, parents with prams, the elderly and others could also profit from this.

What’s important with new technologies is participation. People with disabilities know best what obstacles they come across in their everyday lives, and what tools can really help them. But it’s rare that those affected are actually drawn into the development process. As a result, there’s a host of specially developed products, aids and buildings that they simply can’t use.

New, ever smaller tools and prostheses make it easier to hide our ‘flaws’ and help to promote this kind of behaviour. But if people with disabilities move about self-reliantly in public, with all their supposed flaws on show, this can help us all to overcome them, or at least to re-evaluate them. People will start to have a new image of us, we can dismantle prejudices, and people with disabilities will learn to discover themselves and the world in a self-determined manner.

I’m convinced that technological developments have a decisive impact on how people see disabilities. As a person with a disability, I have a choice: I can either bend to the demands of society and hide my supposed flaws, or I can refuse to allow myself to be defined by what other people find worthy of rejection or acceptance.

Brian McGowan is a historian and a wheelchair user, and as the President of Sensability he campaigns for the equal treatment of people with disabilities. He also works as the diversity officer for the Zurich University of Applied Sciences.

Image: Valérie Chételat

People with disabilities are ‘disabled’ by barriers in their environment and by barriers in the minds of others in everyday life. This hinders their integration and their participation in work and leisure. Some of these barriers – such as steps in public places, or the prejudices of society – can only be dismantled with a great deal of effort. Others can’t be dismantled at all. Modern technology can help to eliminate barriers. For example, new, motorised artificial legs and orthotics – so-called exoskeletons – can support people with disabilities to negotiate otherwise impassable terrain. Smartphones can read information out loud: they both inform people and bring them together. Already today, they help people with visual impairments and limited mobility – and we couldn’t imagine living without them any more.

We mustn’t erect any boundaries to the development and marketing of new technologies where those technologies are employed in a manner that is ethically correct. This means that the technology has to be safe, acquired voluntarily by the user and equally accessible to everyone.

Safe and voluntary – these criteria are largely a given today. There is a challenge, however, with accessibility. Not all members of society can afford these technologies, which are often expensive. That’s especially the case in non-industrialised nations. And in the case of particularly successful applications, the costs are high – not least because high demand drives prices upwards.

The accessibility of new technologies can be improved with market-based means. Innovation cycles should be kept as short as possible; technology transfer should take place in parallel so that new technologies can be offered competitively. And we have to communicate their advantages in a transparent manner. On the other hand, new laws and public money are also making it easier to access new technologies. In Switzerland in particular, there is immense scope for improvement. Disability insurance puts severe limits on financial support for aids for the disabled, which means that state-of-the-art technology does not receive explicit backing.

New technologies don’t put pressure on people with disabilities, but promote the removal of barriers and improve quality of life. To this end, however, these technologies have to be introduced onto the market quickly and widely, if possible with support from the state. If that happens, the greed for profit and the inequitable fight for resources will be rendered irrelevant of their own accord.

Robert Riener runs the Department of Health Sciences and Technology at ETH Zurich and is researching at its Sensory-Motor Systems Lab and at the University of Zurich. In 2016 he launched the Cybathlon, a contest between people with disabilities who are supported by new technologies.