The genomic traveller

A genetics researcher brings ancestral DNA to life

Image: Valérie Chételat

Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas is definitely a very busy woman. She has recently been appointed to the department of computational biology at the University of Lausanne, where she is still setting up her laboratory. “We are still right in the middle of the move… I hope you don’t mind if I eat whilst we talk?”. In the end, we sit in the campus park under a birch tree on a plastic bench. She speaks quickly and enthusiastically, peppering her French with the English words “cool” and “fun”.

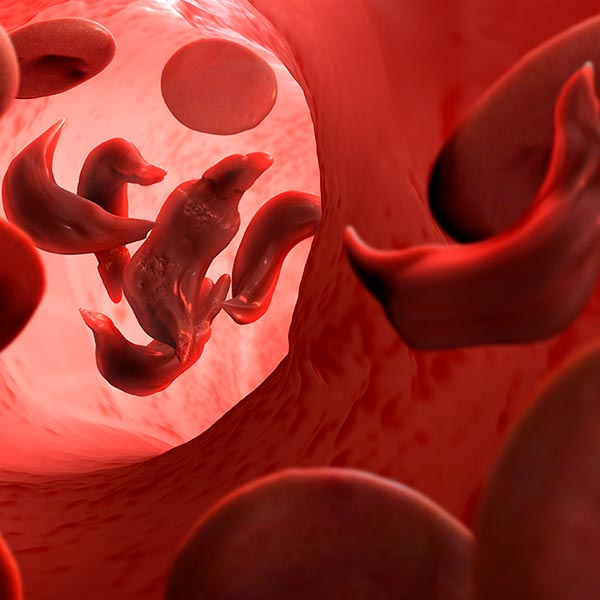

Malaspinas is 35 years old and is studying how our ancestors populated the planet. In particular, she’s looking at how they left Africa, how they adapted to new environments and at which points in history those events occurred. To bear this out, she is turning to both contemporary and ancient DNA samples held in museums, and analysing them using mathematical and digital models. For example, her team is analysing the hypothesis of transpacific contact between Polynesia and the Americas. This is the project that has led her to take ancient DNA samples from Easter Island. For another project, she travelled to South America in response to a phone call from a researcher at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Her correspondent had been studying human remains there and had noted that the genome of certain individuals from a local population, which had lived some several centuries before, was entirely Polynesian.

Her work made waves in the media last year following the publication of an article in Nature on the population of Australia. This research shows that both aboriginal and Eurasian populations arrived in the same wave of migration that had begun in Africa some 72,000 years ago. It put her in the spotlight, which is something she’d rather have avoided. “Journalists intimidate me, but I think that communicating my results in an intelligible way is part of my duty. Society finances my research, so I should give something back”.

No fear, no delay

Malaspinas was born in Geneva and grew up with three siblings and her parents: a physicist father and a Greek artist mother. When she was 17, she spent three months in Crete with her godfather, a chemist at the University of Heraklion. “I would go to his laboratory, asking questions. I was fascinated by the freedom of his work: spending months thinking about one question, discussing ideas, experimenting, beginning again. I realised it was what I wanted to do”. She thought about studying law or literature, but decided to go for medicine. She did not, however, meet the enrolment deadline and had to settle for biology and physics, which she studied simultaneously.

During a class on evolution, she had a “life-changing moment”, at which point she realised she wanted to study population genetics. In the name of love, she set her bearings for California, where she began a Ph.D. at the prestigious University of Berkeley. “I wasn’t afraid and I didn’t delay. I just threw my swimming costumes in a suitcase and left – thinking that Berkeley was closer to Los Angeles than to San Francisco!”. She returned to Switzerland in 2015 after having also spent time in Denmark.

Malaspinas describes her professional career as if she’d just had a long streak of good luck and owed her current position to her fairy godmother. Her postdoctoral supervisor in Copenhagen, Eske Willerslev, sees things differently: “She’s built her career on the basis of a brilliant intelligence and an enormous work ethic”. At the University of Bern, the specialist in population genetics Laurent Excoffier applauds her capacity to link theoretical studies and empirical data. “She’s one of those rare people who can not only develop and implement models but also collect and analyse the samples she’s taken on the ground so as to verify her theories”.

Throughout the interview, her mobile telephone rings incessantly; she also keeps an eye on her watch. Before leaving she discusses a project currently absorbing her attention: a theatre play inspired by her work on populations in Australia, which has already been staged at the Ethnographic Museum of Geneva (MEG) and at the Musée de L’homme in Paris. When asked how the idea came about, she says, “I was teaching statistics, and my students were falling asleep during class… which made me wonder if there was a better way to communicate science, and to reach a larger audience”. This led to the idea of a play for children. Following a meeting with the actor Ludovic Payer, the project began to garner interest among French-speaking Switzerland’s theatre community, including the author of the script Dominique Ziegler and the director Joan Mompart.

The play is set in a museum, where a group of visitors is guided by a young scientist who introduces her work on DNA. The audience is taken on a journey starting with humans leaving Africa and ending on arrival in Australia, where they encounter aboriginal populations. “We wanted to show that science careers are fun. But at the same time, we want to publicise our work, to explain how the genome contains the history of our ancestors and to underscore that we are all relatives and all migrants. In this way, we hope to draw people’s attention to the fate of indigenous populations”. This is another way to give back to society.

Sophie Gaitzsch is a Swiss journalist based in Paris.