Acquiring tomorrow’s skills from today’s computer games

A generation of digital natives is emerging on the labour market. They are able to profit from their video game experience – and not just as pilots or surgeons.

Image: Shana de Neve

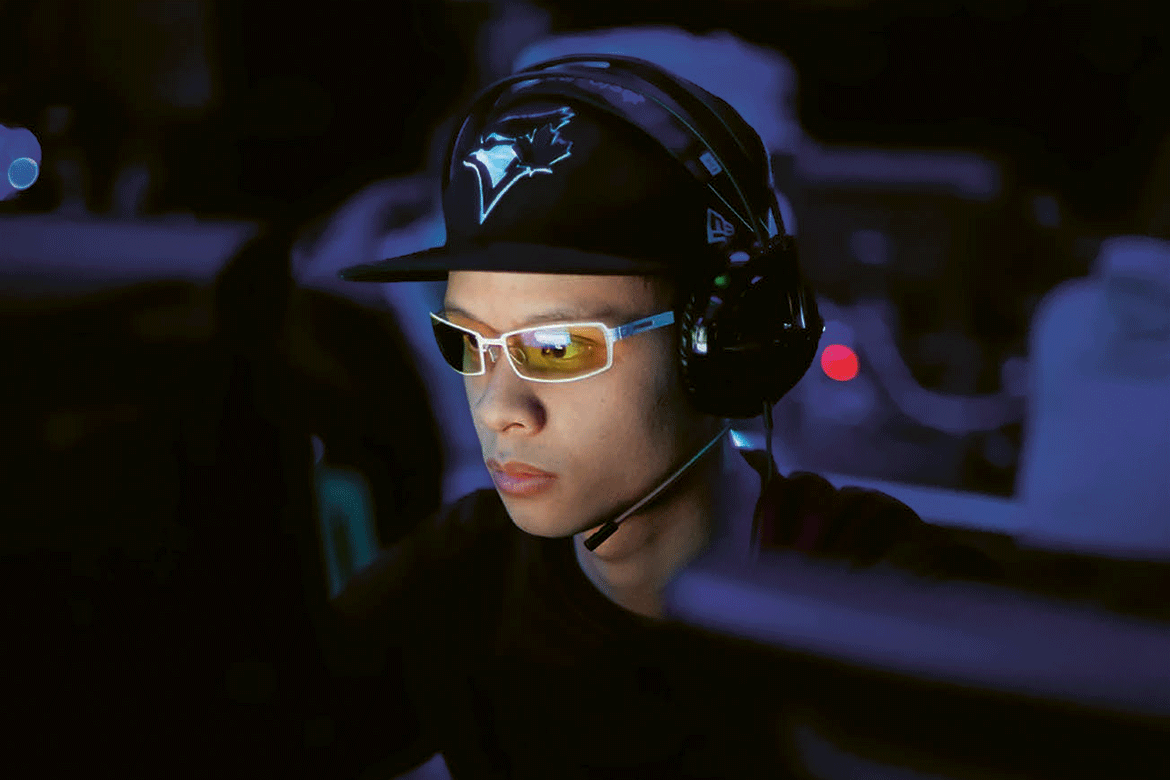

The latest heroes of the sports world aren’t wearing football boots or swinging tennis rackets. They’re sat in front of a PC screen, steering game characters through a virtual world with intense concentration and at high speed. Competitions between different e-sports teams today fill huge halls and promise prize money running into the millions. The many hours spent in front of a PC screen can be rewarded with huge cash sums for elite professional gamers.

But what about all the other young people who also spend a large amount of their free time playing video games? Two-thirds of all young people in Switzerland play them, according to a German-language study carried out by the Zurich University of Applied Sciences ZHAW – in the USA, it’s almost 100%. Meanwhile the world of work is in a state of transition, and so perhaps these gaming hours are not actually a waste of time, but an investment in the future. Experts estimate that progress in artificial intelligence and robotics will mean the loss of half of all jobs. At the same time, many new jobs are being created at the interface between people and technology – and savvy players of video games might well have an advantage in this brave new working world.

Quicker, more precise, and more attentive

Gaming can certainly pay off for budding doctors. These days many surgeons operate in front of a computer screen, steering cameras and surgical instruments inside a patient’s body. In order to carry out this keyhole surgery, doctors need a good spatial sense and excellent hand-eye coordination. Studies have proven that medical students who spent a lot of time playing action-filled video games in their youth have an advantage: they operate quicker, and make fewer mistakes.

For pilots, too, it’s well known that having played video games has a positive impact on skills. Much of pilot training takes place in simulators that are not fundamentally different from the ones on PCs at home. And there’s even a completely new profession where the skills learnt from gaming can be transferred one-to-one. Drone pilots control their unmanned planes all over the world via computer screens – with the important difference that their drones don’t fly over imagined landscapes, but in the real world.

Meanwhile, there are indications that gamers might have an edge in other jobs too. The American educational expert Marc Prensky coined the phrase digital natives in 2001, postulating that their brain structures were changed permanently by the time spent at computers. They thought differently, processed information differently, and also approached problem-solving differently.

And indeed, a systematic analysis of the scientific literature proves that playing video games can influence your cognitive abilities. One of the first people to investigate this was the neuropsychologist Daphne Bavelier from Geneva. Her research is concentrated on a specific category of action video games – so-called ‘first-person shooters’ and ‘third-person shooters’. “These games are extremely complex and variable”, says Bavelier. “The players have to keep many objects in their field of vision at one and the same time, and are constantly being bombarded with new information”.

One typical research approach is to compare people who play regularly with those who have no experience of action video games. However, this kind of experiment risks being skewed by unknown factors. For example, it might happen that people with better visual perception actually have a preference for playing video games, and do so more often. This is why researchers also carry out experiments under controlled conditions. To this end, they seek out test subjects without any experience of video games and divide them up into two groups. One group plays an action game such as Call of Duty, perhaps for 50 hours in total, divided up over 12 weeks. The other group spends the same amount of time playing a simulation game such as Sims, which has no action elements. The test subjects then sit standardised cognitive tests both before and after the 12 weeks, and the results of the two groups are compared.

With the help of such experiments, Bavelier and her colleagues have discovered that a whole series of abilities are developed by the players of the action games. The effects were noticeable across all levels of cognition – from simple perception to complex mental processes. The players of the action games were better able to differentiate between different shades of grey, and were able to keep more moving objects in view on the edge of their visual field. They were able to process information quicker and had shorter reaction times, and they scored better results even when it was a matter of making decisions and solving problems. They were also able to switch quicker between two tasks or carry out several tasks at the same time.

Bavelier believes that the common reason for these positive effects is selective attention – in other words, the ability to concentrate on one task despite a multitude of information and impressions; this entails shutting out anything that is not essential. Another important finding is that the abilities learnt in action games can be transferred to real situations. For this reason, Bavelier is convinced that this provides people with an advantage in the new world of work: “Ultimately, just about everything we do in the 21st century is based on our interaction with computers”.

Playing is work

The business world has long known about the positive effects of video games, and is advancing the introduction of game-like elements at the workplace – a process now called ‘gamification’. “More lifelong game players have entered the workforce, so the idea of using games for teaching no longer seems quite so odd”, write the American game developers David Edery and Ethan Mollick in their book about the introduction of video games to the business world. For them, combining work and play is no longer something contradictory. Specially developed games – so-called ‘serious games’ – could in future help to train employees, optimise processes and improve teamwork. In a best-case scenario, such games could even make onerous tasks seem like fun. Edery and Mollick describe one company, for example, that created its own game in order to entice its employees into testing a new software version.

The US Army scored a jackpot with its first-person-shooter video game ‘America’s Army’, in which the player proceeds through the training programme of a US soldier and has to fulfil missions that are close to reality. The idea was to convey a realistic picture of the army, and thereby find suitable new recruits, both male and female. The great success of the game means that it today also serves for schooling and practice purposes. Not every company can pay out a two-digit million-dollar sum for a tailor-made video game, but even simple puzzle games or simulations can increase our productivity, say Edery and Mollick, and at the same time provide fun at the workplace.

Dominik Petko, a media lecturer at the Schwyz University of Teacher Education, is also looking into serious games. He sees great potential in them, for both schools and further education: “Some games have been very well designed, and you can use them, for example, to teach second-grade kids linear equations”. But there are also very bad games, he says, that offer absolutely nothing. “So our question is this: What are the design principles and design elements that distinguish effective games from those that are less effective?”

In order to find this out, Petko compares the learning impact of the same game in different variations with different school classes. In one variation, for example, the cute character will be missing, while in another, you can’t collect reward points. His goal is to find an attractive game that engages its participants, but at the same time doesn’t occupy too much cognitive capacity, instead leaving enough space for the learning process. Petko also believes it’s important that the tasks set by the game are neither too simple nor too difficult, and that the game automatically adapts to the ability of the player.

More social competence

The University of Zurich is currently testing another application of serious games. They don’t just want them to impart educational content, but to shape our ethical consciousness. “Ethics education in its current form is usually rather distant and boring, if I may be allowed to exaggerate a little”, says the ethics researcher Markus Christen. “People sit together and discuss things”. Together with Carmen Tanner and colleagues, he’s now developed a ‘serious moral game’ that is intended to impart ethical values in the financial sector.

In this game, the participants can be advisors to a big company, for example, and they keep getting into ethically tricky situations – such as dealing with the confidentiality of documents. “By being immersed in the game, the players should find out more about themselves as moral beings than if they were merely to engage in abstract reflection”, says Christen. But he doesn’t believe that playing a game alone is sufficient – “it’s probably also important for players to reflect afterwards on their behaviour during the game”. They are currently carrying out experiments to see if his hypothesis is correct. They are also working on a serious moral game for training medical students in ethics, focussing on the conflicts of interest that occur in everyday medical work.

This project by the University of Zurich is founded on the realisation that video games can have a positive influence not just on cognitive abilities, but also on social behaviour. However, this depends very much on the content of the game. For example, the social psychologist Tobias Greitemeyer of the University of Innsbruck had test subjects play prosocial video games like ‘Lemmings’, in which the players have to protect small, helpless creatures from danger. A control group played the classical, neutral game Tetris. Afterwards, they were all confronted with a test situation, and the players of the prosocial games were more willing to help than those who had played the neutral game. Other, similar studies have confirmed the link. Prosocial games promote prosocial behaviour. According to Greitemeyer, longer-term studies have shown that the effects measured are long-lasting, even if video games are only one of many factors that influence social behaviour.

Nor did these metastudies find proof of any connection between video games and violent crime. “When it comes to the risk of someone running amok, video games play either a minimal role or none at all”, says Bodmer. Whether or not someone is likely to become violent is mostly determined by other factors such as domestic violence or the consumption of alcohol or drugs. In Germany, politicians have already reacted to this all-clear signal. “Although the country has some of the strictest youth protection legislation, video games there are hardly ever placed on the index any more, but are offered uncensored to anyone aged 18 or older”.

However, other metastudies have also found a direct correlation between video games and aggression. These contradictory findings come about primarily because the individual studies chosen for analysis are selected and assessed by researchers according to different criteria. So among researchers, this topic is still far from closed.

New forms of teamwork

Many companies are already making use of these findings, and get their employees to play collaborative video games together – in hopes that a good team in the virtual world will also work well together in the office.

In this regard, so-called Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs) are of particular interest. These include games such as World of Warcraft. In these games, which are often played by more than a thousand people at once, the characters can make friends with each other and come together in teams in order to fight common enemies. Psychologists believe that new forms of friendship, leadership and collaboration are being developed in these virtual worlds.

In fact, a study commissioned by IBM entitled ‘Virtual Worlds, Real Leaders’ has identified several elements that are characteristic of virtual teams in MMORPGs. The leadership structures in these games are often merely temporary – according to the task at hand, someone else can take on the leadership of a group. It’s also possible to make mistakes, because if something goes wrong, you simply start again from scratch. This makes the team leaders more courageous in the decisions they make, and means they are more likely to take risks. According to the business magazine Forbes, people applying for jobs are now starting to list leadership experience acquired in MMPORGs on their CVs in order to prove that they are well adapted to the working world of the future.

Just how much these principles can truly be applied to the real world remains an open question. Already today, lots of people are sitting on their own in a ‘home office’ and only communicate virtually with the rest of their team. But there’s also help underway to counter this increasing isolation in the workplace. The use of virtual reality software is intended to give employees the impression that they’re sitting in the same room as their colleagues, even if they’re actually spread all over the world. Soon, virtual reality will be helping us to design new products, test prototypes and visualise data. “One day, we believe this kind of immersive, augmented reality will become a part of daily life for billions of people”, wrote Mark Zuckerberg, boss of Facebook, on his blog. So it seems unavoidable that the workers of the future will have to cope with virtual reality too. The young people of today, sitting at home and playing the latest video games with their virtual-reality glasses, are unwittingly preparing themselves for the working world of the future.

Nevertheless, a study conducted by ZHAW has found that almost nine percent of young people in Switzerland are engaged in problematic use of the Internet, which suggests addictive behaviour. These at-risk groups also play video games significantly more often. According to addiction experts, this becomes dangerous when the young people in question are online so much that they hardly have any time left for sleeping, eating or schoolwork, and when the virtual world becomes the centre of their lives. For this reason, ZHAW is arguing in favour of more preventive measures, such as offering alternative leisure activities in which young people can experience themselves as sufficiently competent that they don’t have to seek the feelings of success they get from playing video games.

Yvonne Vahlensieck is a freelance science journalist who lives near Basel.