Networks in times of war

The path to peace is easier if individual groups can be convinced to withdraw, instead of just banning arms shipments to them.

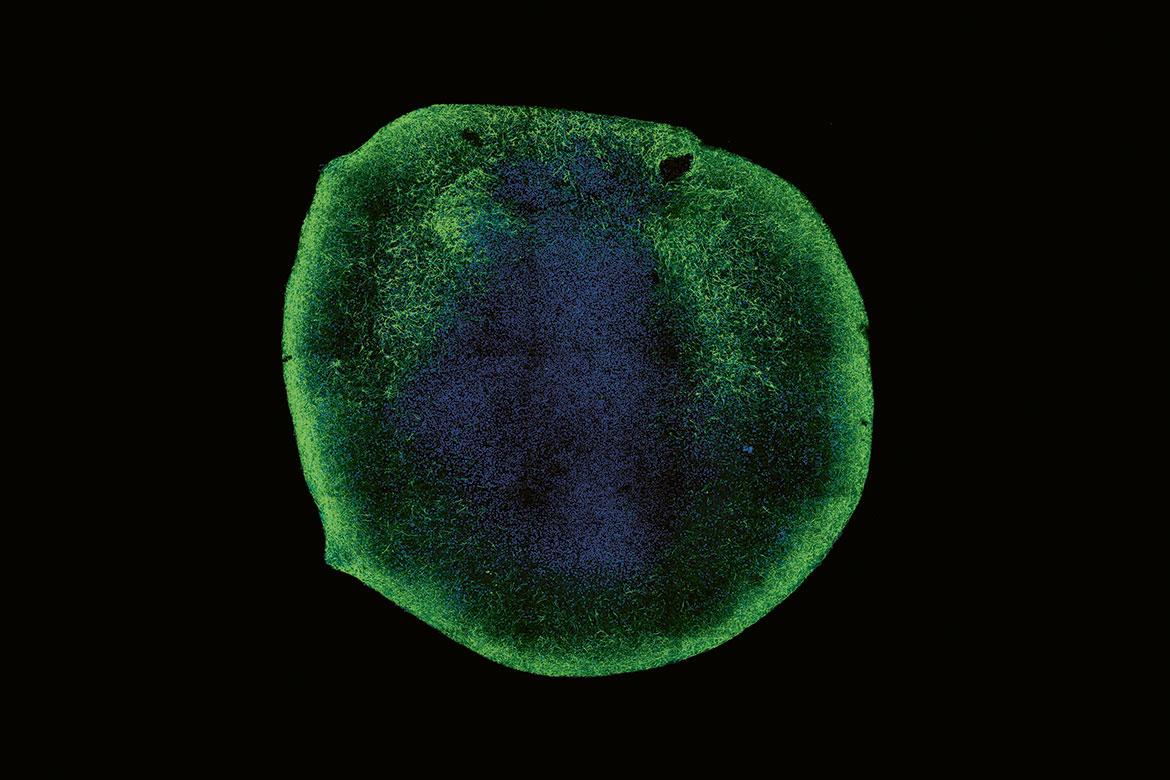

The militant Union of Congolese Patriots was only founded towards the end of the war. | Image: Keystone/EPA Photo/DPA/Maurizio Gambarini

The most recent civil wars in Africa and the Middle East are fundamentally different from the conflicts that took place during the Cold War. Instead of having two camps, each supported by a different major power, current conflicts often involve dozens of different groups that come together in shifting tactical alliances. The political options for achieving peace are correspondingly multifarious. But what measures can achieve the desired success?

The economist Michael D. König of the University of Zurich has developed models to further our understanding of networks in the emergence of such conflicts, and also our knowledge of research collaborations and supply chains. This can help us to explore the efficiency of political measures. Using the Second Congo War of 1998-2003 as an example, König shows how networks and the behaviour of the participants (80 militant groupings) influenced each other. For example, one group would intensify its actions in the conflict when its allies reduced theirs during a rainy period, or when its opponents increased their own battle efforts. Banning arms shipments to one group can reduce its activity by up to 60 percent, but will not necessarily reduce the overall number of battles because its allies will fight all the more intensely.

“Greater success is achieved through negotiations that lead to specific warring parties exiting the conflict”, explains König. “When all foreign groups withdraw, according to our model, the number of combat operations reduces by 41 percent”. His results thus also demonstrate the war-mongering impact of neighbouring states.

Nicolas Gattlen