Accepting uncertainty

Experts should no longer be seen as oracles, writes Nic Ulmi. The political process must not be based solely on facts, but also on values, interests and opinions.

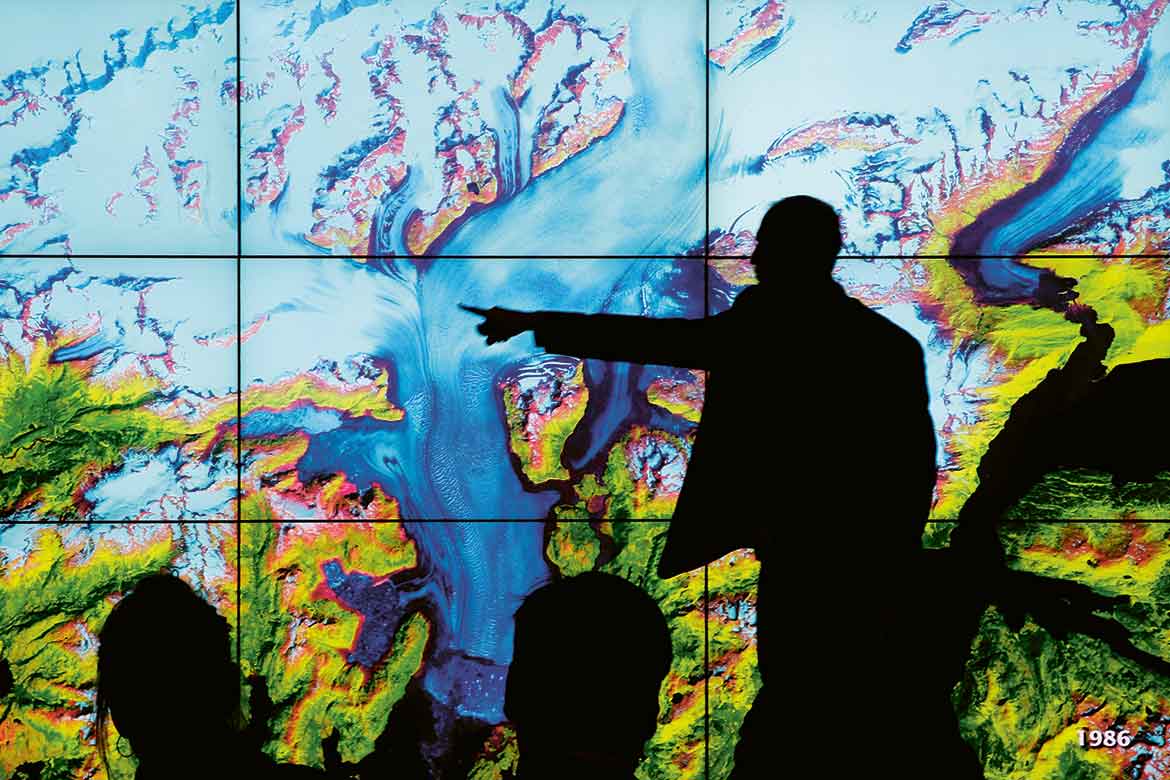

An attentive audience or critical doubters? An expert in action at the US pavilion of the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris. | Image: Keystone/AP Photo/Christophe Ena

Imagine it’s 1979. A woman prepares lunch in her kitchen: fried eggs, steak, buttered toast. A burst of light fills the room and a man appears: “I come from the future. Don’t eat those eggs, they’ll clog your arteries!”. The intruder disappears and the woman follows his advice, taking the plate to the rubbish bin. But she is stopped in her tracks by another flash as the man reappears. “Stop, we made a mistake! There are actually two types of cholesterol ...”. The scene repeats itself many times over, each time with new instructions on how best to protect your cardiovascular health: “No steak!”, “No bread!”, “Doesn’t matter what you eat, get fit!”, “Give up! It’s genetically determined!” and so on. This is the general gist of Funny or Die’s video ‘Time Travel Dietician’ that heralded the arrival of the ‘crisis of expertise’ in our homes in 2017.

We may laugh, but behind the joke there is a more serious issue. A tidal wave of doubt has swept away the certainties that science seemed to carry. Conflicting results and political attacks have shaken confidence. Having been dragged from a situation where expertise would guide our individual and collective choices, the citizen is now left deafened by the cacophony of opinions. Yet this state of affairs can also be seen in a better light: as a reconciliation with the doubt that is actually at the heart of science, a clarification of the disagreements through which all knowledge is constructed, an uncovering of conflicts of interest often present in expert reports. All of this can lead us – perhaps – towards a more mature and less naïve relationship between science and society. It would be a relationship where scientists bear a little less responsibility for transmitting the Truth and instead become more involved in the democratic game. And here’s how it might happen.

The dream of a rational policy

“To understand the situation, we have to go back to the source of what is known as evidence-based policy”, says the Swiss political scientist Caroline Schlaufer, who currently holds a position at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. The term appeared in Great Britain in the 1990s, under Tony Blair’s government. It describes the intention of the authorities to base their actions on empirically proven facts, rather than on ideology or belief. The expression became fashionable and the social sciences finally decided to look into it and see whether scientific data really are being used in policy, and if so, how.

The result was clear. “In the real world, there is almost never a simple scenario where scientific evidence directly guides policy decisions”, says Schlaufer. Policy development involves negotiations, bargaining, the affirmation of values etc. Factual elements are not absent from this process, but they play a limited and generally instrumental role. They are used a posteriori to justify political positions whose origin was far from scientific”. Schlaufer ties this in with the narrative use of empirical facts: “A politician never states raw facts: on the contrary, the facts are only put at the service of a narrative that designates a problem and proposes solutions, or that denounces the poor solutions proposed by a competing party”. Others are still less shy about the practice. With an ironic play on words, they denounce ‘policy-based evidence’, in other words, the creation of evidence in order to support political will.

The question of public confidence in experts is also subject to empirical checks. This is indeed the idea behind the Swiss Science Barometer – conducted by the Universities of Zurich and Fribourg – which measures people’s attitudes towards scientific knowledge. The results are rather comforting: “Confidence in science is high”, says Julia Metag, a co-director of the project. “In Switzerland, it is even a little higher than in the other countries where it is measured. The majority of the population agrees that political decisions should be based on scientific results”. She adds a few provisos, however: “Trust in scientists employed by industry is lower than trust in those working in universities. And it is in areas that polarise public opinion that there is more mistrust, such as anything even remotely related to animal experimentation”.

Crisis? What crisis?

The Barometer’s data stretch back to 2016, the beginning of the era of Donald Trump, post-truth and fake news. Has the situation worsened since then? “In the United States, the 2018 Science and Engineering Indicators survey, which measures the same variables as our Barometer, shows that scientists remain one of the most trusted groups in society as a whole”, says Metag. In countries such as the United States and Germany, where longitudinal data are available, this confidence remains stable over decades. “We don’t see any sign of the collapse that’s so readily evoked by the media”.

So where does this crisis of perception come from? “In my opinion, there are two new phenomena”, says Schlaufer. “One is ‘expert bashing’, an activity common in certain political movements. The other is the response to these attacks over the past two years whereby scientists have felt a need to raise their voices in the political arena. They have become more and more present in the media to defend their work”. According to Schlaufer, this recent phenomenon does not necessarily reflect a growing politicisation of expertise, but rather, the current exacerbation gives greater visibility to an older fact: expertise had been long politicised before the ‘crisis’ now being deplored.

This is also the diagnosis of Jason Chilvers, the head of the 3S (Science, Society and Sustainability) research group at the University of East Anglia (UK). “Controversy in areas such as climate, bioengineering, nanotechnologies, GMOs or fracking have undermined the traditional popular view of science as an independent, objective field, set apart from the rest of society”. This old vision was first challenged in the post-war period. “The breakdown of unconditional trust in science and technology can be seen very clearly in that period. That was when, for example, environmentalist and anti-nuclear currents began to question not only the harmful effects of innovations, but also the motivations, values and interests at work in science”.

In this sense, scholarly controversy is a reflection of opposing world views and societal projects. “Research can be neutral in itself, but what takes place upstream generally isn’t – by this I mean the definition of the problem we want to study”, says Schlaufer. According to Sheila Jasanoff, a founding figure in the sociology of science and a professor at Harvard University, it represents the calling into question of what she recently termed the “founding myth of expert authority: the separation of facts and values”.

The ‘problem’ of the public

At the same time, a reconfiguration of the relationship between science and society is taking place. “Great efforts have been made over the last three decades in many countries to develop forms of debate between scientists and the public”, notes Chilvers. In preparation for the climate conferences in Copenhagen in 2009 and Paris in 2015, for example, there was a series of citizen deliberation sessions. “By the way, this has shown that citizens are quite capable of making very sensible judgments on highly technical issues”.

This participatory approach has its grey areas, says Chilvers. “The public is often defined as the problem. Consequently, the process sometimes aims to cause behavioural change among the population in a way that has been defined as desirable in advance by the public authorities”. It is the policy of soft persuasion, known for a decade as ‘nudging’, through which individuals are led to adopt practices that appear to them to be the result of a personal choice rather than a constraint.

It would therefore be a question of broadening the process, Chilvers continues, considering that the public can also provide some of the solutions. “Outside the official spaces of participation, there are a great many people who are confronted in their daily lives with problems such as climate change, and they undertake extremely varied forms of action ranging from full-blown activism to changes in the way they shop for household goods, and to finding local solutions for their energy supply. “People do interesting, innovative things that often stay under the radar”. Chilvers is involved in a long-term project, presented in the book entitled ‘Remaking Participation’, which aims to raise awareness of these forms of participation. The reconfiguration of the relationship between science and society requires the cards to be re-dealt: experts are invited to put aside their role as educators and listen to social practices that remain largely unexplored.

Facts alone are not enough

Underlying the ‘crisis of expertise’ is, therefore, another phenomenon: a broad movement of accepting uncertainty. It is modifying the mutual expectations of experts and the public and proposes renewed roles for both. “Scientists should not just communicate their findings”, says Metag. They should talk about the processes used to construct their results, express their opinions, and engage in discussion with the public”. And if possible, they should resist the temptation to withdraw from the debate out of spite, when they see that their studies are being misused. The media, for their part, should “give a better view of how science works, with its limits and margins of error”. They should also continue to play their role as safeguards, adds Schlaufer. “Sometimes political authorities commission studies and then hide the results when they fail to meet expectations. In general, the study then ends up in the hands of the press and becomes public anyway”.

In conclusion, “it is naïve to think that scientific evidence or research results can be the decisive factor in a democratic process: it never happens”, according to Schlaufer. Individual and collective decisions need facts, and to produce facts means turning increasingly to experts. But our choices should also always take on board values, interests, opinions and day-to-day experience. This web of elements is rooted outside of the purity of empirical evidence and reasoning.

Nic Ulmi is a freelance journalist. He lives in Geneva.