Long wings for cold flight

In high latitudes, bodies become bigger and extremities smaller. But the rules for insects are slightly different.

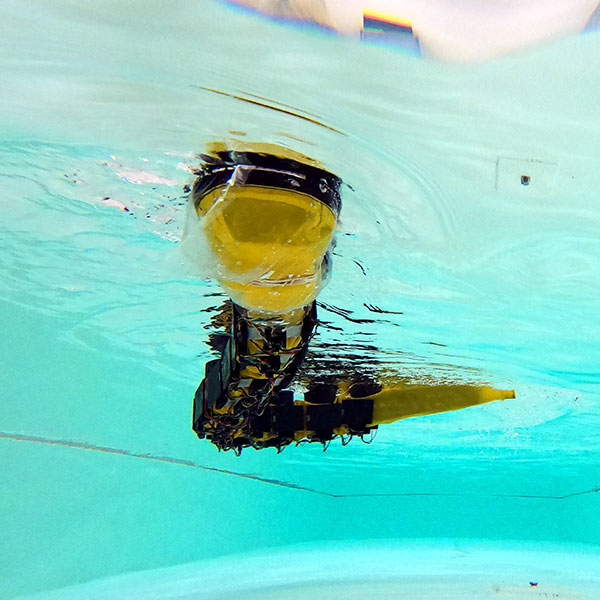

A different body mass for different environments. Here’s a different fruit fly: Drosophila repleta | Wikimedia Commons

An Arctic fox wouldn’t last long in a desert, nor would a desert fox do well in the Arctic. Indeed, most animals in the colder regions of the Earth grow bigger in its warmer climes than related species – although their ears are smaller. The cause of these evolutionary adjustments lies in temperature balance: a large volume with a small surface area means less warmth is lost. Smaller bodily extremities also prevent heat loss.

These facts are proven for warm-blooded animals like mammals or birds. But researchers at the University of Zurich, together with colleagues from the USA and Sweden, have now been investigating whether or not the same rules apply to insects. To bear this out, they looked at museum specimens and at data on over 150 species of fruit fly. And they found out that flies do become bigger in higher latitudes.

“The reason for this could be a physiological reaction to local temperatures” says Patrick Rohner, the primary author of the study. Insects grow slower when it gets colder, but at the same time, their development time is extended so much that this is more than balanced out. Whether or not this larger size provides flies with an evolutionary advantage in the cold is still unclear, says Rohner.

But in colder regions, the flies’ wings were also longer – which is the converse of the rule with warm-blooded creatures. Rohner explains that shorter wings have no effect on the temperature balance of the creature. “Flies are so small that they immediately take on the outside temperature”. However, longer wings have a clear advantage: calculations have shown that they help flies to generate thrust with less energy. This means they can take to the air, even at lower temperatures – perhaps to try and find a warmer spot, for example.