Modesty versus ignorance

Attention, empathy and patience: proven communication strategies can help scientists convince even the most sceptical.

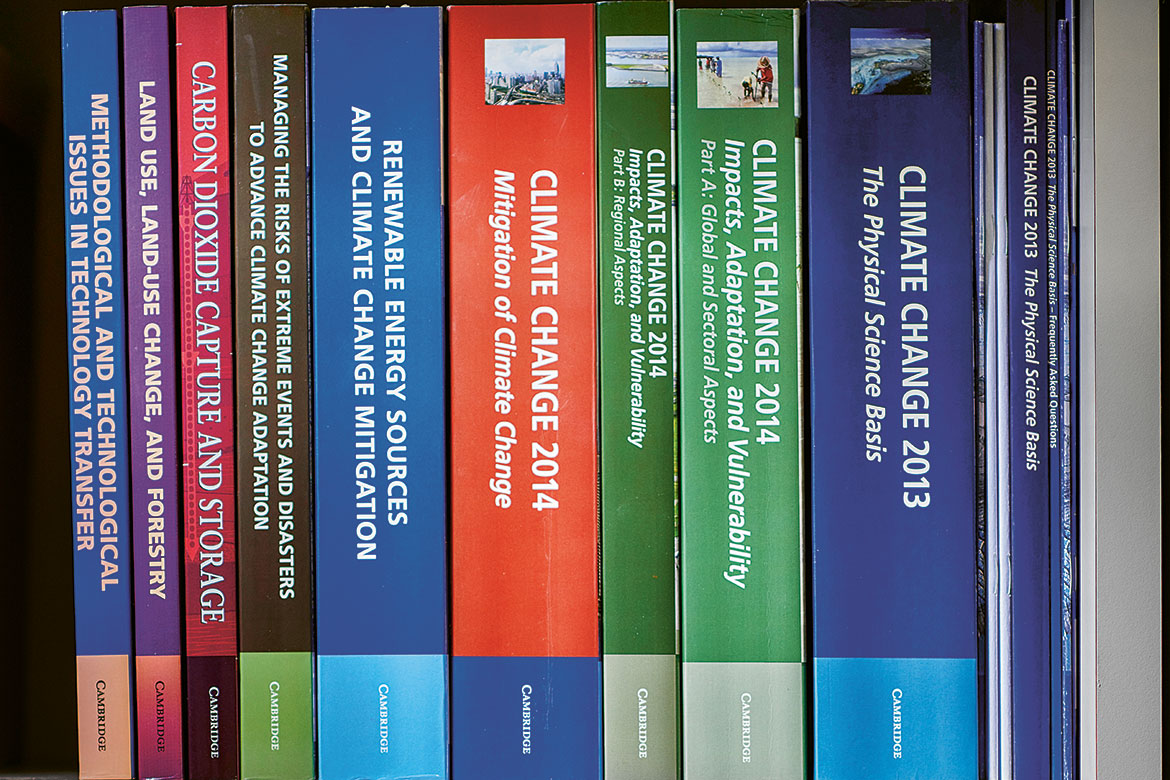

Scientific knowledge on climate change fills libraries. But it has done nothing to change the opinion of the climate sceptics - on the contrary. | Image: Manu Friederich

Today’s world is increasingly dominated by emotions, slogans and imagery. Those who use factual argumentation are struggling to punch at their weight. For Tom Nichols, prosperity is at fault: as steeped in abundance as we are, we tend to forget that the basis for our health and comfort is not opinion, but fact.

This ‘crisis of expertise’ is only part of a larger problem. The modern world is losing its interest in the future, preferring to roll in the gains of the present, as is reflected in a growing distrust of ‘elites’ and disdain for institutions. Given these circumstances, it’s difficult for scientists to correct the impressions of the general public. Their rational arguments will fall flat with audiences that adopt positions couched in terms of self-defence and identity.

But giving up is hardly an option. When addressing society’s woes, experts must double-down on common-sense and even-handedness. To be heard above the raucous citizens, they must avoid the many pitfalls that end in antagonism, such as impatience, paternalism and hyper-factuality. Courage must also be sought to undertake the effective strategies of marketing and communication sciences: aim to understand before being understood, show empathy, know when to step aside.

For some time now, sociologists have been telling us that ideas are only accepted when communicated by the trustworthy. In the light of the current erosion of scientific authority, individual experts stand virtually no chance. The smart way forward, therefore, is to listen to the advice of communications professionals: analyse the target audience, identify the key stakeholders and focus on them.

Scientists tend to keep their noses to the grindstone, but such dedication can be counter-productive when it comes to crossing swords with wary citizens. There’s little place for modesty in academia. It is, however, an essential tool for convincing the most sceptical.

Daniel Saraga, Editor in chief