Subterranean surprises

Research is just as varied underground as above it. We take a glance at what lies beneath.

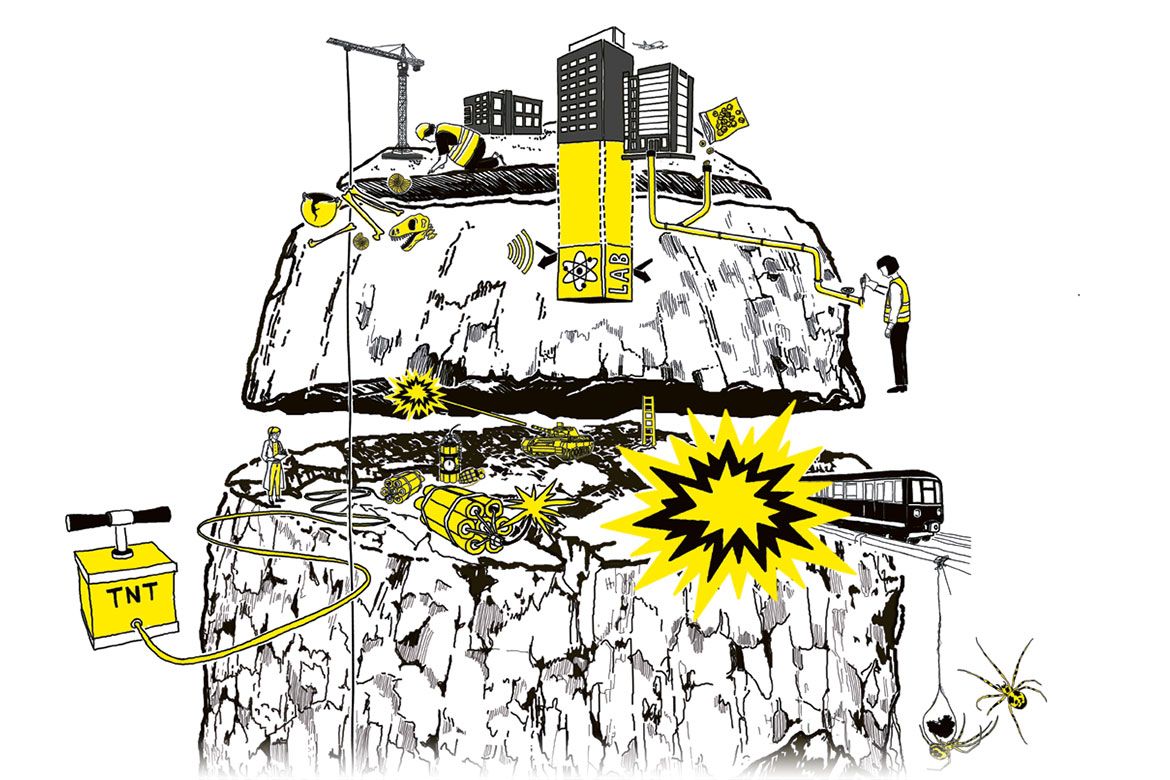

Test tunnels near Flums in the canton of St. Gallen: a playground for pyromaniacs

Hammer drills are doing their best against the surprisingly tough limestone rock, while flak cannons fire off into the dark. Here in the Hagerbach Test Tunnel near Flums in the canton of St. Gallen, researchers are able to carry out their more extreme tests. Deep in the mountain, it’s not so bad if smoke alarms and fire extinguishing systems have their quirks – so fire detectors can also be tried out here too. If they fail, you can resort to hand-held extinguishers instead. This tunnel was actually created almost fifty years ago as an experimental site for tunnel engineers so that they could work under the most realistic conditions possible. They tested their machines and their explosives so successfully that they ended up with an extensive tunnel system many miles long. Now there’s enough space down here for all kinds of research projects – the kind that appreciate the discretion the place offers, and for which the geological ‘cushion’ provided is much appreciated.

Excavations: messages from the past

When construction machinery unexpectedly uncovers old artefacts of scientific value, the machines give way to archaeologists who rummage through the earth in their stead – with the appropriate degree of caution, of course. These messengers from the past can be hundreds of years or millennia old, and sometimes they are also revealed by soil erosion. That’s when emergency excavations become necessary, which always keep archaeologists working at full capacity. But the archaeologists of today prefer to leave their findings where they turned up in the first place, because that’s where they are best protected, and where the most contextual information can be found. The earth is the best archive; only where the archaeological substance is directly threatened do archaeologists begin excavations. Archaeology is really a kind of controlled act of destruction, says Armand Baeriswyl of the Institute of Archaeological Sciences in Bern. Incidentally, archaeology in Switzerland is the responsibility of the individual cantons. The Swiss Civil Code states: “Ownerless natural bodies or antiquities of scientific value are the property of the canton in whose territory they were found”.

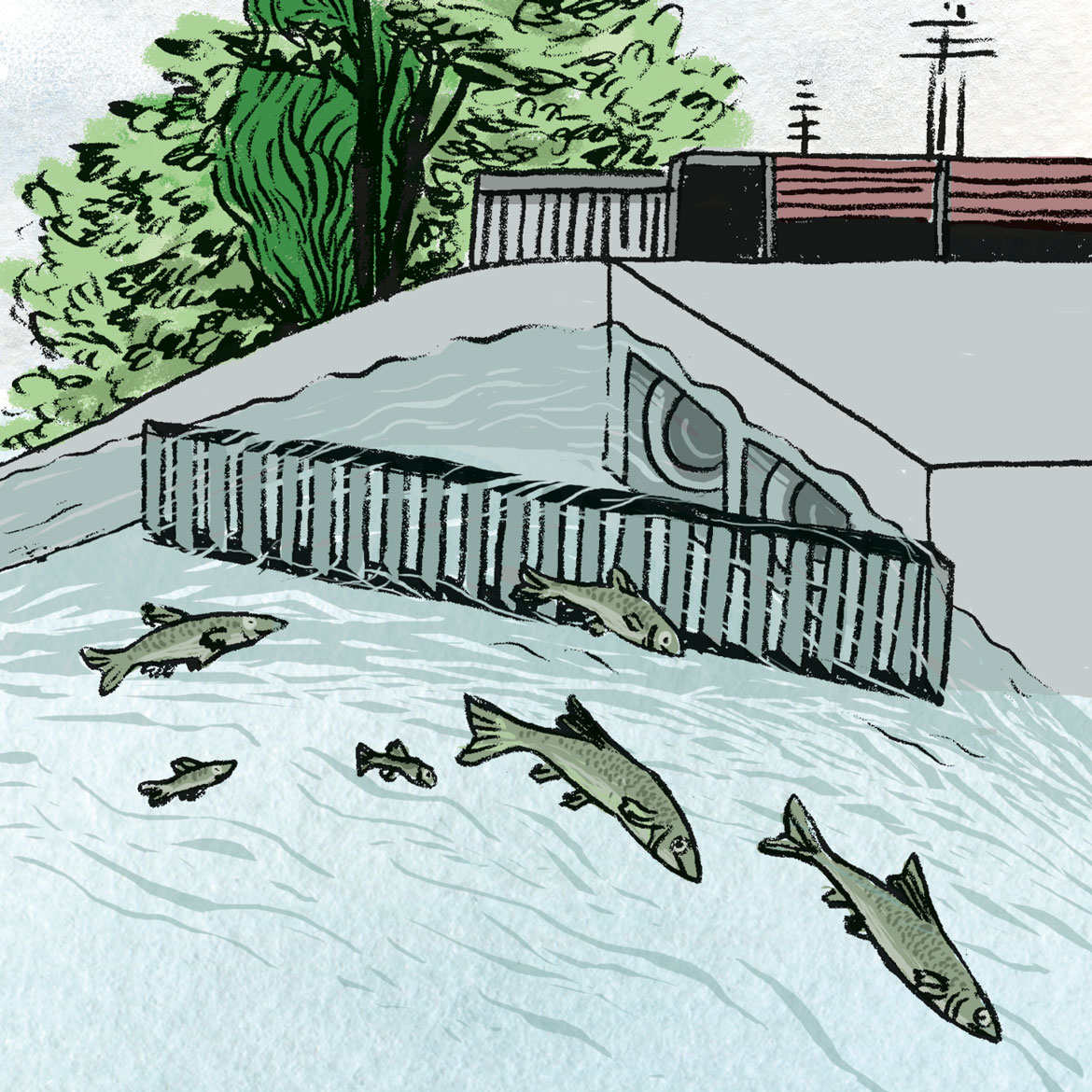

Municipal sewage systems: Corpus delicti in the water

You could almost say that the sewage system is the subconscious of our urban existence. When researchers descend into the sewers, they engage with tangible aspects of our history – such as chemical residues. The research conducted by Christoph Ort of the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (EAWAG) in Dübendorf has achieved a certain fame because he has succeeded in calculating drug consumption in different cities just by sampling the tiniest concentrations in waste water. A team run by Frank Blumensaat at the same institute is currently constructing an urban hydrological field laboratory in Fehraltdorf in the canton of Zurich. They want to investigate a town’s complete water circulation system, so they’re installing modern sensors for rainfall, flow rates and water levels in order to create detailed models of outflow processes in an urban environment.

Laboratory in Rüschlikon, canton of Zurich: floating experiments

Vibrations, sounds, temperature differences – for nanotech experiments, everything has to be reduced to the minimum. IBM has been lucky in Rüschlikon, because the layer of soil and clay below its research centre there is only eight metres thick, under which there lies conglomerate rock. They have built a nanotechnology centre here on a concrete base that’s fixed directly to the rock, independent of the rest of the building. Their six noise-free labs are unique in the world today. But it would be more accurate to say that these labs (or at least their working surfaces) ‘hover’ above the rock. The foundations themselves pick up the nanometre-small vibrations of the cars on the motorway about a hundred metres away, but the labs – all 50 tonnes of them – float on a cushion of air to avoid all extraneous vibrations. This means that all kinds of nanotech experiments can be carried out here under conditions that are quieter and more constant than anywhere else in the world. The labs are also completely shielded off from all electromagnetic rays and from acoustic noise. The temperature does not even fluctuate during an experiment by more than 0.01 degrees Celsius.

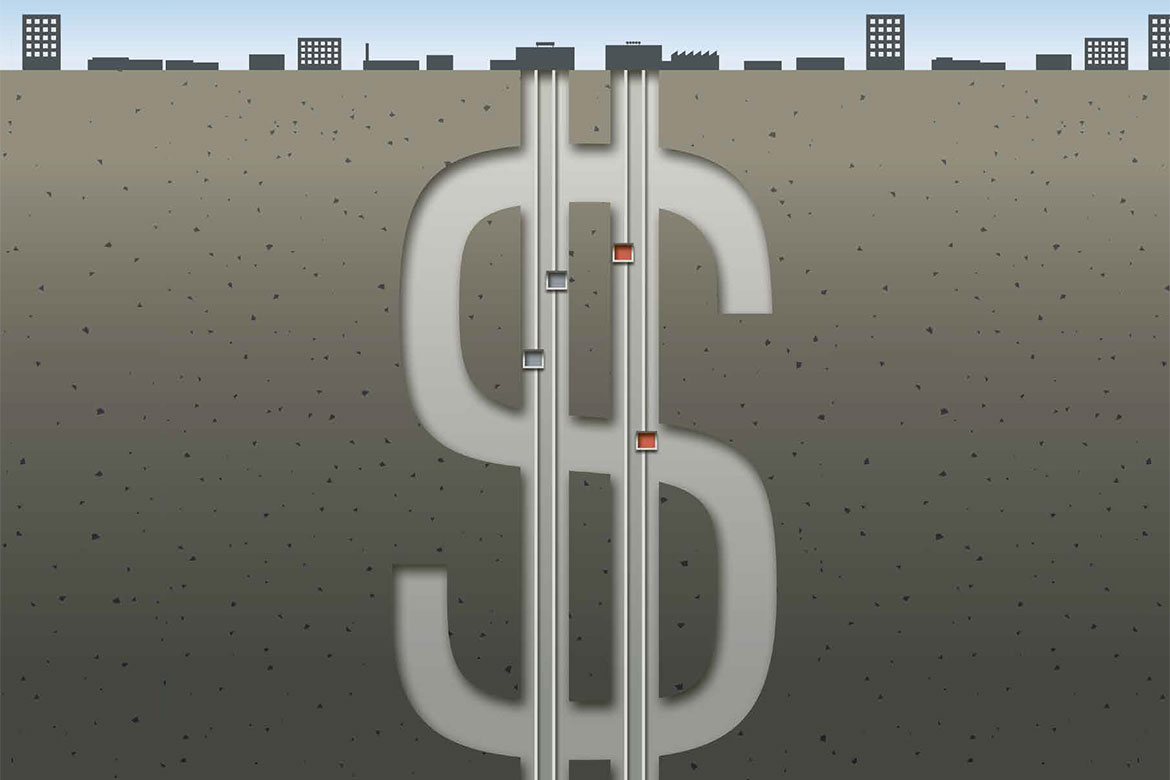

The tunnel in the Mont Terri, canton of Jura: Micro-organisms help to store atomic waste

This mountain never lets you alone. Mont Terri divides the Ajoie district from the rest of the Jura, so it was only a question of time before people started tunnelling through it. First the railways came, then the motorway. But because people have meanwhile found out that its Opalinus Clay is one of the most stable, impermeable geological stratifications, an experimental tunnel has been created alongside the motorway tunnel, where research can be conducted into the storage and management of atomic waste. This project brings together fifteen international partners and is being coordinated by Swisstopo. No actual atomic waste is being brought to Mont Terri, nor will any storage facility ever be built here. The tests they carry out are of a different kind. Recently, for example, one young researcher from EPFL was able to show that the dangerous hydrogen gas released by the corrosion of the steel containers can be removed by micro-organisms that are being cultivated nearby.

Cave systems: amateurs discover pseudo-scorpions

They’re dark, cold and wet – caves are inhospitable places to live. At least for human beings. Some animals feel positively at home in this ecological niche, but because it’s small and badly lit, the study of these animals – called biospeleology (or ‘cave biology’) itself exists somewhat on the margins of science. There’s only a few specialist scientists who devote themselves to environments underground – and cave researchers usually have other things in mind than trying to find out what’s actually alive down there. Biospeleology is thus an ideal field for citizen science. Sometimes, amateur scientists come up with specimens that can then be classified by specialists. Recently, three new species of pseudo-scorpions were discovered in Hölloch in the canton of Schwyz, in the Jura, and in the Schrattenfluh caves in the canton of Lucerne.

Infographic: Vollkorn