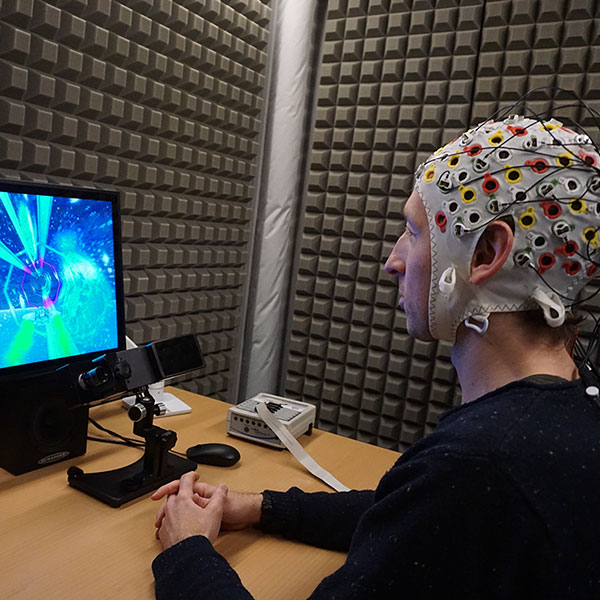

Can neuroscience help psychiatric practice?

Brain imaging, genetics and animal experiments continually advance our understanding of the brain. But is this knowledge useful for treating patients with psychiatric disorders?

Image: Valérie Chételat

It is undeniable that the contemporary practice of psychiatry is far removed from the confinement approach of the 1950s. The development of neuroleptics has led to a radical change in the treatment of psychosis. Psychotherapeutic approaches have diversified considerably and their effectiveness is now scientifically established. Finally, the deinstitutionalisation movement has led to the development of community-based care and a change in attitude towards patients, who now play a central role in defining their treatment.

However, developments over the past forty years have been limited to improving existing concepts. Progress continues to run into the same obstacles: unclear definitions of diagnoses lump together patients who likely present different diseases under the same banner, huge variations in response to treatments that have no effect on many aspects of symptomatology, high rates of side effects, and no impact on social functioning.

Our lack of knowledge of the neurobiological mechanisms that cause psychiatric disorders plays a central role in this situation, and this is where neuroscience must contribute to improving clinical practice. Such knowledge would increase the validity of diagnoses and enable the development of drugs that act on the cause rather than the consequences of diseases. Identifying biomarkers would strengthen early intervention strategies, one of the major hopes for progress in psychiatry.

Is this just a utopian vision of an inaccessible future? Not really. The National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) Synapsy brings together clinicians and neuroscientists to work on these issues. For example, the study of the role of a deficiency of brain antioxidants in psychosis has been particularly encouraging. A randomised trial in young patients with psychosis demonstrated that giving them a supplement with a precursor of glutathione – the main cerebral antioxidant – leads to clinical improvement in a subgroup identifiable by a measure of redox imbalance in the blood. The biological action of the treatment is confirmed by the observed increase in intracerebral glutathione levels and the restoration of white matter.

Although there are scant areas of psychiatry in which this type of approach is useful, there is an urgent need to invest energy in them. To do otherwise would be to turn our backs on much-needed progress for patients. Of course, this should not be a choice made at the expense of current approaches, but the opening up of a new perspective that will improve them.

Philippe Conus is a professor at the University of Lausanne, co-director of the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) Synapsy, and the head of the general psychiatry department at the CHUV (University Hospital of Lausanne).

Image: Valérie Chételat

It’s fair to say that, without a brain, there is no mind and thus no mental illness. But it is too early to conclude that “psychiatric illness is a disease of the brain”, in other words, that neurobiological knowledge of the brain allows us to understand the psyche and better treat psychiatric disorders.

The ‘psyche’ is an emerging concept and, although it is clearly the result of neurobiological processes, it is more than the sum of the parts. The properties of the psyche – and especially of what is known as ‘consciousness’ in the broader sense – are not precursors of the brain’s constituent parts: they are the result of their interaction. And the complexity of this interaction still clearly exceeds the available research resources today.

To search for the causes of psychiatric illnesses in biology is to take what is called an essentialist posture. From this vantage point, a diagnosis is used to label a disease by considering it as a natural thing that existed a priori, even before the question of its existence was asked, thereby making it a process of discovery. On the other hand, nominalists such as myself see a disease as being defined only in terms of its possible utility; it is therefore not to be ‘discovered’ but to be ‘built’. The diagnosis is therefore a political process: the result of a social consensus that can change at any time depending on the contexts and interests at stake.

To confuse brain disease with psychiatric illness is to make a so-called category error: a thing belonging to a particular category (here the brain, which belongs to biology) is attributed to a different category (i.e., psychology). However, these are two completely different areas, irreducible to each other. It would be the same kind of mistake to claim that it is possible to reveal the artistic genius of a Picasso based on the chemical structure of the canvas and the colours of one of his paintings. It is misleading not only to say that synapses think, but also to say that the brain thinks. Neuroimaging does not let us see thoughts, motivations, or emotions, even though it can show neurobiological events that – ideally – are correlated to psychological phenomena.

This is not a plea against the scientific method, that is, the formulation of hypotheses and their falsification. It is, however, crucial that they be correctly formulated. In the same way that we should avoid mistaking sociological for geological hypotheses, we should not mistake biological for psychological hypotheses.

Daniele Zullino is a professor at the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Geneva and head of the Addiction Department at the University Hospitals of Geneva (HUG).