Feature: The changing face of Big Science

Knowledge and power: humanity’s ambition in six projects

From genetics to space, 25 years of colossal scientific projects have redefined our relationship with knowledge. Lessons to be learned from six Big-Science projects

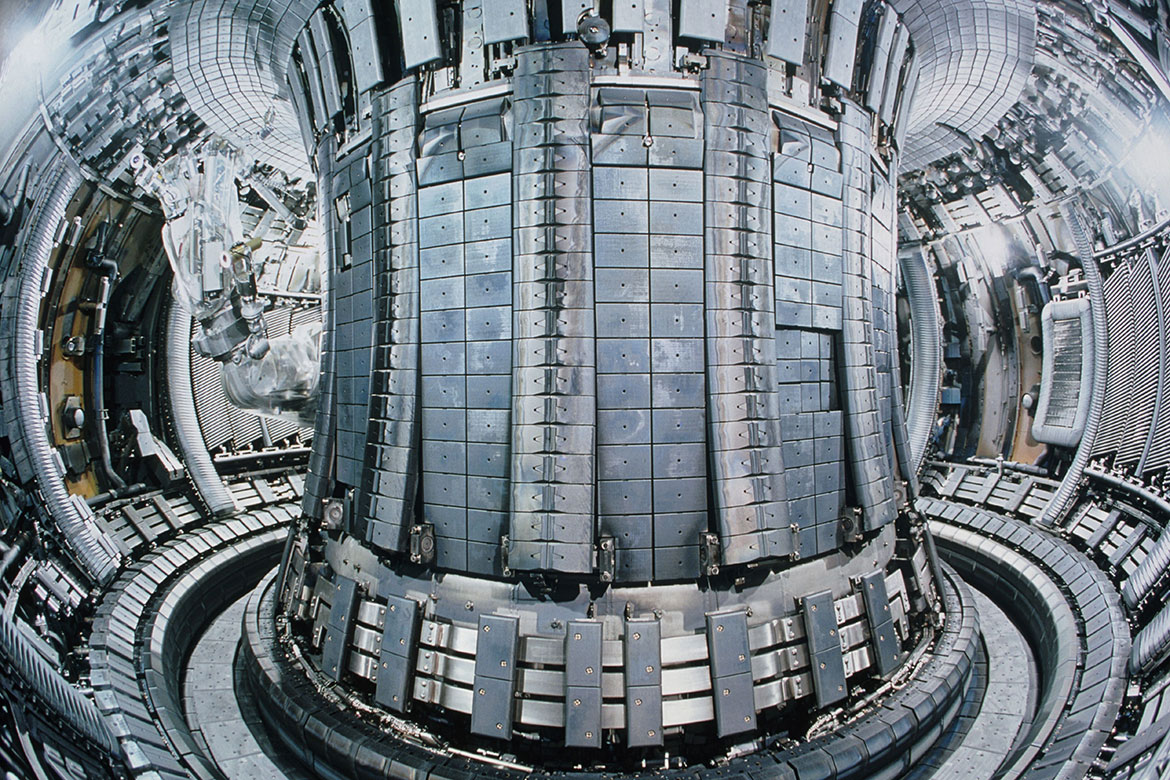

In nuclear fusion reactors – like the Joint European Torus (JET) near Oxford, UK, shown here – the temperature reaches 100 million degrees Celsius. | Image: Keystone/Science Photo Library/EFDA-JET

International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER)

Duration and location: 2006-2025, Cadarache, France

Objective: to verify the scientific and technical feasibility of nuclear fusion as a new energy source.

Superlatives: the most complex scientific effort of all time; a project that amounts to “lighting a sun on earth”.

Applications: supposedly clean and unlimited energy.

Estimated cost: EUR 20 billion.

Actors: China, the EU, India, Japan, South Korea, UK, USA.

Landmarks: governance, design and budget issues lead to a change of management in 2015.

Limitations: A wide range of critics point to technological obstacles such as the development of sufficiently strong material, doubts about the effective safety of the technology, and the risks of abandoning other areas of renewable energy research or of being overtaken by private initiatives such as start-up Commonwealth Fusion Systems, General Fusion of British Columbia or Tri Alpha Energy.

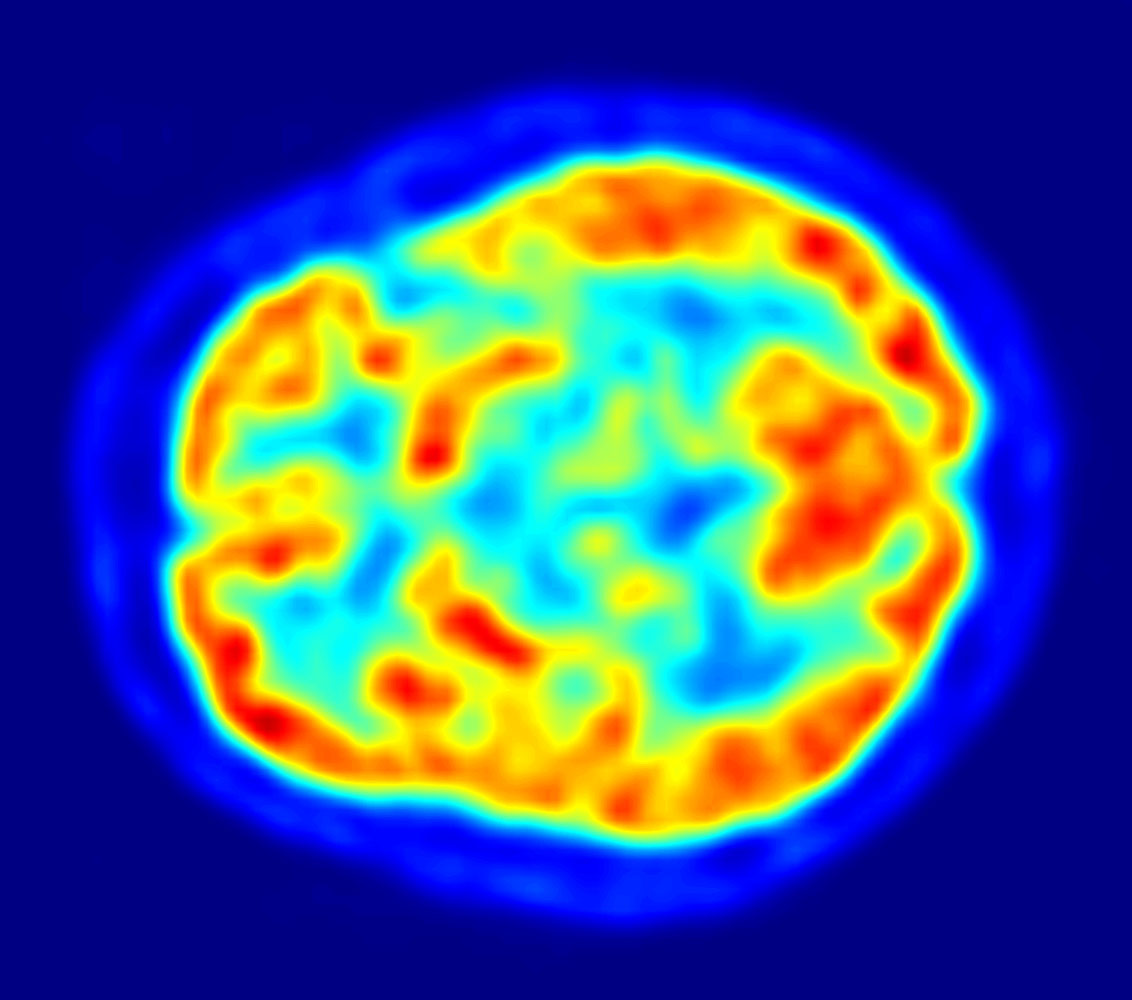

The human brain | Image: Wikimedia

Human Brain Project (HBP)

Duration and location: 2013-2023, EPFL, Lausanne

Objective: to reproduce the functioning of a human brain on a supercomputer.

Applications: medicine, information technology.

Estimated cost: EUR 1 billion.

Actors: the EU, EPFL and some 100 research institutes in about 20 countries.

Landmarks: in 2014 a group of 750 scientists signed an open letter to the European Commission criticising the centralised management of the project and the marginalisation of cognitive neuroscience, which led to a reorientation of the project, a change in its governance and a redefinition of its objectives – developing tools for neuroscience and computing. A fresh crisis struck in August 2018 with the resignation of the executive director Chris Ebell.

Limitations: “We have switched to an industrial project approach. The European Commission (…) now requires these platforms (…) to deliver ‘products’. But I’m not sure that this technology-led approach will enable us to answer the major scientific questions posed by the human brain”, says Yves Frégnac, the former project coordinator for the CNRS, the French National Center for Scientific Research.

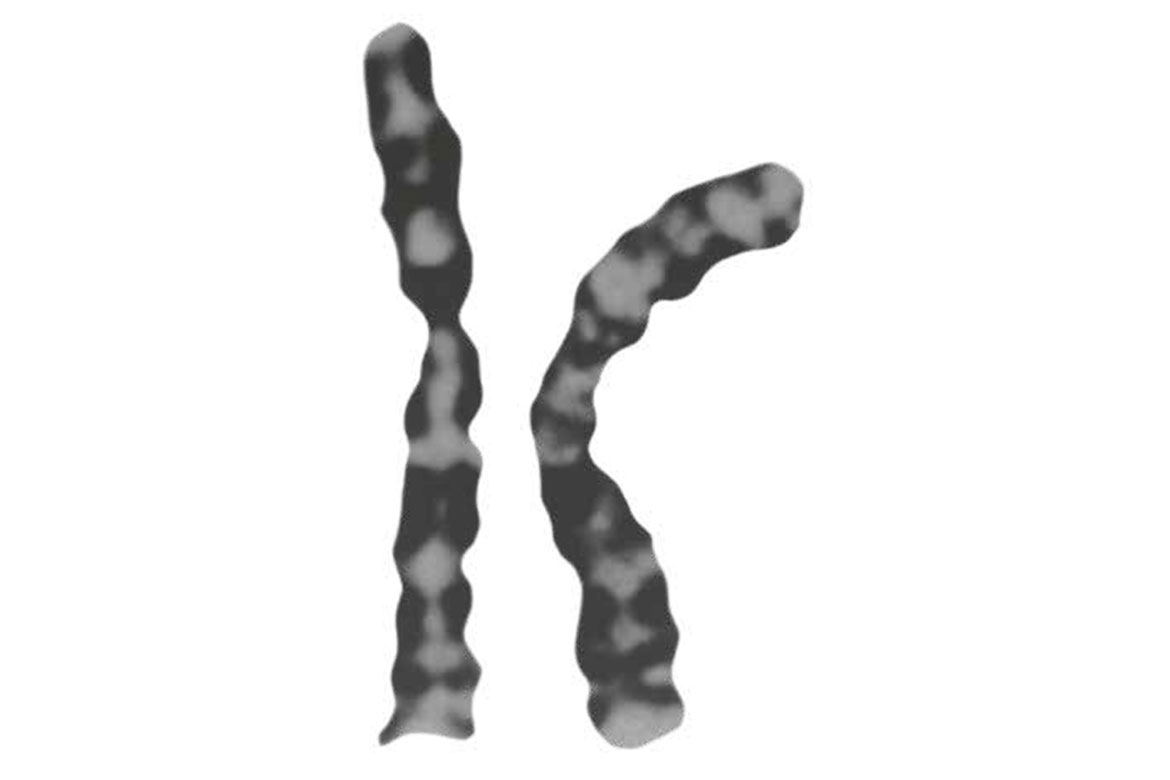

DNA | Image: Keystone/Science Photo Library/ Science Vu/Visuals unlimited, inc.

Human Genome Project

Duration and location: 1990-2003, five different locations, UK/USA

Objective: to determine the DNA sequences of the human species.

Superlative: the largest collaborative project of all time in biology.

Applications: medicine, forensic sciences, sequencing technology.

Cost: USD 2.7 billion (below the announced budget of USD 3 billion).

Actors: the American National Institutes of Health, the British Wellcome Trust, some twenty research centres (CN, DE, FR, JP, UK, US).

Landmarks: fierce competition is taking place with Craig Venter’s Celera Genomics company, which plans to monetise access to results; the ensuing debate led to the obligation to abide by the principle of free access to genomic data.

Limitations: the expected medical applications are slow to come; and “seventeen years after the initial publication of the human genome, we still haven’t found all our genes. The answer is more complex than we had imagined”, says the computational biologist Steven L. Salzberg.

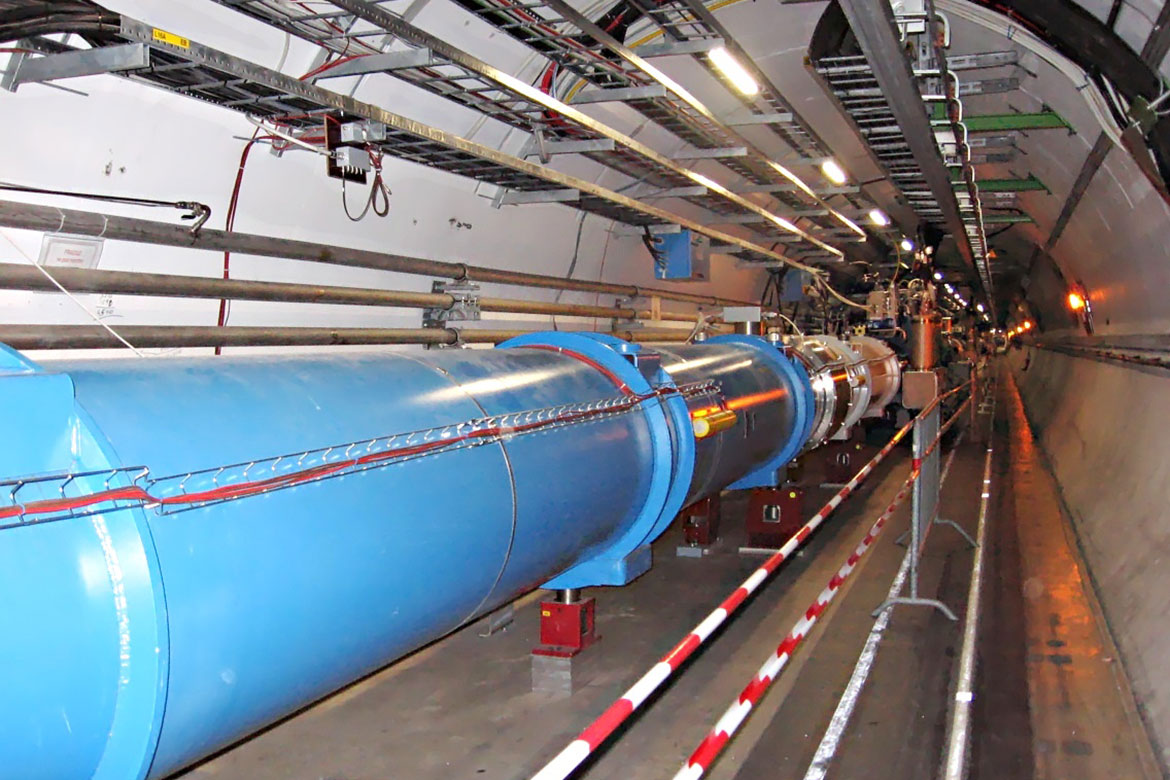

CERN | Image: Wikimedia

CERN

Duration and location: 1954-, Geneva

Objective: to understand what matter is made of, where it comes from, and what fundamental forces govern the universe.

Superlative: the Large Hadron Collider is 26.6 km in circumference, accelerates protons to 99.999999991% of the speed of light, and generates 6 GB of raw data per second.

Applications: primarily, knowledge. Nevertheless, CERN has led to many innovations in medicine (imaging), the environment (sensors) and, of course, information technology (management of big data and the invention of the World Wide Web in 1989).

Cost: annual budget CHF 1.2 billion.

Actors: 22 European States and Israel.

Landmarks: CERN stimulates the imagination, from the supposed possibility of a black hole that could engulf our planet, to fears of human sacrifices and antimatter bombs.

Limitations: Conclusive evidence of the Higgs boson in 2012 was a triumphant success, but it raised a problematic question: contemporary particle physics needs surprises if it is to reach a grand unified theory.

ISS | Image: wikimedia

International Space Station (ISS)

Duration and location: 1993-2028, Earth’s orbit

Objective: to study human adaptation to the space environment for lunar and Martian missions; international cooperation; continuous human presence in orbit (18 years so far).

Superlatives: the most expensive object ever built.

Applications: materials science, energy, meteorology, medicine, space tourism.

Estimated cost: USD 150 billion.

Actors: NASA with the Russian, European, Japanese and Canadian space agencies.

Landmarks: the Columbia space shuttle accident in 2003 and budgetary problems delay the work; in February 2018, the Trump administration announces that it intends to privatise the ISS.

Limitations: The debate on the effective contribution of the ISS to scientific research periodically resurfaces. The number of studies conducted on board has finally increased since 2010, but is not enough to develop “a convincing argument in favour of scientific research on board the ISS”, said the political scientist William Bianco 2017.

Laser | Image: wikipedia

Extreme Light Infrastructure

Duration and location: 2013-2018, four locations, EU

Objective: four interdisciplinary laser-based technological platforms; European cohesion.

Superlative: the most powerful lasers in the world.

Applications: materials, medicine (hadron therapy), radioactive waste destruction, etc.

Budget: EUR 850 million.

Actors: European Union; Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania.