Monopolising Lake Zurich

Every two weeks, Jakob Pernthaler and his team take water samples from the deepest spot in Lake Zurich. He tells us here about Burgundy blood algae, a little boat, and a lakeside research station in Kilchberg.

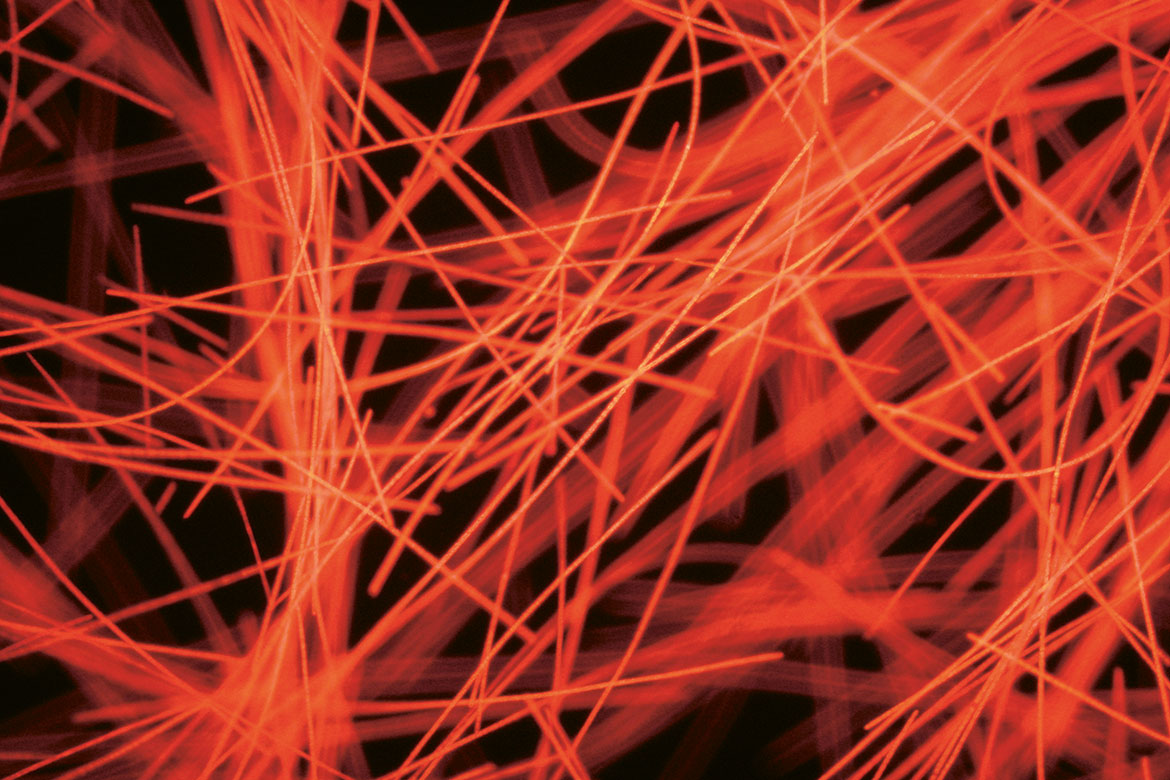

Burgundy blood algae turn Lake Zurich red | Picture: Limnological Station of the University of Zurich

“Lake Zurich is so important because it provides more than a million people with so-called ecosystem services. This includes high-quality drinking and process water. The lake is also a recreation area where people go swimming and boating. Ninety percent of the lake’s banks have been created artificially, and the water level too is controlled artificially, by means of the weir system at the Platzspitz in the middle of the city of Zurich. The water of the lake is replaced almost completely every year, thanks to the influx from the Sihl Lake and the Linth Canal.

We work at the Limnological Station of the University of Zurich, and every two weeks we take a boat onto the lake to take water samples from different depths, ranging from 20 to 120 metres. But we can’t erect any kind of fixed research platform for our measuring instruments at the deepest point of the lake (which is 136 metres deep). There is too much traffic. The official fleet of Lake Zurich is like a public bus service, and everyone else has to make way for them. But with our little boat, we’re flexible. What’s more, we also have a lake water pipe that leads directly to our laboratory at our Station in Kilchberg. The temperature of the upper layer of the water has risen by almost half a degree since the 1990s. This change means that you can see a reddish film on the surface of the water by the lakeshore in late autumn – and, more rarely, in spring too. This is a mass phenomenon caused by certain algae, the cyanobacteria, which are called Burgundy blood algae in the vernacular. They live in the weak light found between 10 and 15 metres below the surface, and only there. In spring and autumn, however, their red filaments rise to the surface. Even despite the increasing cleanliness and clarity of the water, these cyanobacteria have become more common in Lake Zurich over the past 20 years. Incidentally, their name “Burgundy blood algae” was given in honour of the Battle of Murten of 1476, when the Swiss defeated the Burgundians and the water of the Murten Lake was said to have been coloured red by all the blood of the dead and wounded.

Like little submarines

We are also researching into how global warming and the concomitant shifts in the seasonal water-mixing processes can promote the growth of Burgundy blood algae. They have gas bubbles in their cells that enable them to steer down to their optimum depth, rather like little submarines. But if they go deeper than 80 metres, the water pressure makes their gas bubbles implode. That is the only way to eliminate the algae. But global warming means that water mixing occurs today only down to 60 metres in depth. The result of this is that most of the cyanobacteria are able to survive the winter. What’s more, they defend themselves against predators using a strong poison that is also dangerous to humans – in larger doses, it can lead to diarrhoea, vomiting and even liver damage. Ozonisation during the treatment of drinking water means that this poison is destroyed. But at present the mass of Burgundy blood algae is monopolising the lake. Regrettably, they are eaten neither by small crustaceans nor by young fish. That’s why the Zurich Lake is no El Dorado for fish any more.

In their lab, the researchers are investigating single-cell organisms that live in the water and feed off the poisonous algae. | Picture: Limnological Station of the University of Zurich

But it would be wrong to claim that the lake is too clean and that more nutrients would do it good – such as manure from farms. In my opinion, the biology of the water has altered to the detriment of the fish, but the most important task of the lake, in terms of its ecosystem services, is providing drinking water. So the current high quality of its water is ideal. In our basic biological research, we are also interested in how micro-organisms feed off the poison of these algae. At the Limnological Station, we are investigating single-cell organisms that eat the Burgundy blood algae without being damaged themselves. In principle, however, our research team isn’t searching for ways to eliminate the Burgundy blood algae from the lake. Its mass occurrence is a natural process that is being scientifically monitored by us. As soon as there is a really cold winter, a large number of them will be destroyed. Such a winter will mean their monopoly of the Zurich Lake is at an end – at least for the following year”.

The scientists of the Limnological Station of the University of Zurich conduct their research from a villa on the banks of Lake Zurich. | Picture: Limnological Station of the University of Zurich

Jakob Pernthaler is often out on his boat, checking the progress of the Burgundy blood algae. | Picture: Limnological Station of the University of Zurich

Jakob Pernthaler has been running the Limnological Station of the University of Zurich in Kilchberg since 2011. He is a professor of aquatic microbiology, specialising in bacteria, limnology, microbiology and environmental microbiology. He completed his doctorate at the Department of Zoology at the University of Innsbruck, after which he was based at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen before moving to the University of Zurich in 2005 as an assistant professor.