Feature: Taking a fresh look at school

What education research tells us about learning outcomes

Extensive studies have been conducted into what makes for successful learning. But the findings of education research rarely reach the classroom. We look at what research can offer, and what schools can do with it.

Meta-analysis has helped us to understand what it is that allows students to achieve lift off. | Image: Nicolas Zonvi

There’s a lot written, discussed and debated about schools and education. Most people have a firm opinion on what schools ought to do, what they ought to achieve, and how they should be run – whether we’re teachers, parents or politicians. And we’re often reluctant to change our opinions. Nevertheless, we all want the same thing: the best possible school education for our children.

Hattie’s monster study

In recent decades, education research has made much progress in determining how school lessons can be organised to help children learn as best they can. Nevertheless, “in many classrooms, the findings of education research are still not sufficiently acted upon”, says Wolfgang Beywl, an education researcher at the FHNW University of Education. He sees a chasm between research and teaching practice – one that is difficult to overcome for both sides. And the way politicians talk about education also pays too little attention to the insights provided by research.

But let’s take things one at a time. The prominent education researcher John Hattie has conducted extensive research into the factors that can influence a child’s educational success. He comes from New Zealand, but teaches today at the University of Melbourne in Australia. He carried out a veritable monster study in which he evaluated all the English-language literature about educational success at school. This comprised 800 meta-analyses of more than 50,000 studies of 250 million school pupils, both girls and boys. It took him more than 20 years. Hattie presented his results in his book Visible Learning in 2009. “This book had a big impact back then”, says Wolfgang Beywl, who has meanwhile been co-responsible for translating it into German, and whose own research builds on Hattie’s findings. For the first-ever time, people beyond the confines of the school system began talking about the learning success of children, and how to improve it.

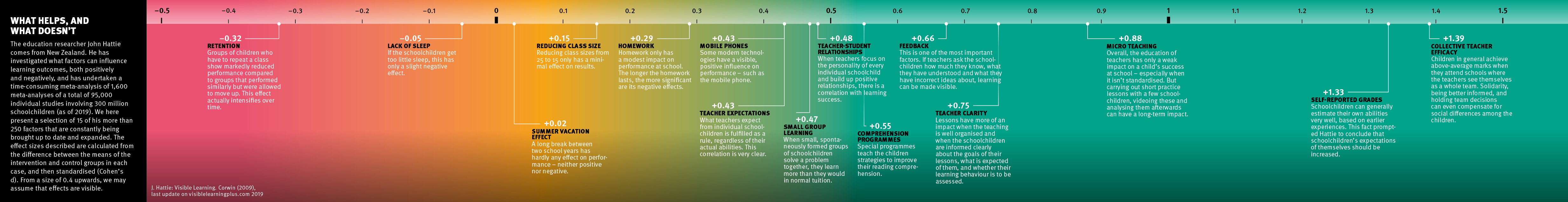

Interactive graphic (below): scroll the graphic left and right with your mouse or by swiping.

Since then, Hattie has been adding ever more analyses of education studies. Today, he has carried out more than 1,600 meta-analyses of a total of 95,000 studies. He has identified over 250 factors that influence how children learn – either supporting them or hindering them – and he has also determined just what their impact is. These influence factors include the clarity with which teachers express themselves; learning techniques; the feedback culture in a school; and homework.

The teacher is key

Hattie’s analyses brought forth unexpected results, not least in the realm of homework. According to Hattie, homework doesn’t help children to learn at all, at least not in their early years at school. It is only in the latter stages of secondary school (from the age of roughly 15 upwards) that it might possibly be of help. “But even then, it very much depends on the type of homework and whether the learners get useful feedback about it”, says Beywl. Factors that generally have to do with school structures or school resources have a surprisingly low impact on learning success – factors such as class size, or to what extent children are divided into different streams or schools based on ability.

By contrast, Hattie recognised that roughly 100 of the success factors involve teaching actions and methods employed in the classroom. And many of these factors have a major impact. “Hattie thereby proved empirically that the teacher’s behaviour in the classroom is decisive”, says Beywl. In fact, teachers can have a truly decisive influence on the learning outcomes of their pupils: roughly 30 percent of the total learning success depends on their behaviour, claims Hattie.

Of course, Hattie is also the recipient of criticism. “He made several miscalculations”, says Beywl. But that is hardly surprising, given the immense volume of the data he analysed. For example, Hattie calculated simplified mean values, though he and Beywl later corrected this mistake together.

The flaws of education research

The results of the research by Hattie and by many other education researchers have hardly had any impact on teaching practice. In other words, they haven’t found their way into the work of teachers in the classroom. One reason for this is that education research does not have the same universal validity as, say, research in the natural sciences. “Experience has shown that the results of many studies can hardly be generalised, because they are heavily dependent on a specific context”, says Stefan Wolter, the head of the Swiss Coordination Centre for Research in Education. Put differently: results from one country can’t be transferred easily to other countries. The same can even apply between schools in the same country. So, a concrete measure that is proven to function well in some schools might be completely ineffective in others.

There are other problems, too. “Education researchers can rarely implement a clean study design”, says Wolter. That means carrying out a study with a large number of participating school classes with randomly assigned groups and control groups. In such a study, a specific measure would be tested on some of the classes, while the control classes would receive their ‘normal’ tuition. In reality, however, systematic mistakes occur from the very fact that schools volunteer to participate in studies instead of being selected randomly.

Nevertheless, studies have still been carried out in Switzerland using co-called comparable control groups – groups that are similar to the test group in terms of age, gender and social background. Urs Moser is an education researcher at the University of Zurich, and he has been able to carry out individual studies of this type in which all the schools of a canton have participated.

But even this procedure cannot replace having a randomly chosen, unbiased selection. The data could still contain other confounding variables, because so many factors influence the learning process – even the suburb in which the children live. “We can never completely control such extracurricular factors, or illustrate them perfectly in the data”, says Moser. This makes it difficult to reach any universally valid conclusions.

Teachers study themselves

All the same, Hattie’s work teaches us several quite fundamental things: that there are important factors that influence the learning success of schoolchildren, and that lie directly in the hands of the teachers. Instead of relying on their own intuition, teachers can assess the efficacy of their own teaching, says Beywl, by creating a data-driven basis that enables them to improve their teaching systematically.

Together with his research team, Beywl is trying to explain to teachers just how this works. They have developed a package of tools that they call ‘Making teaching and learning visible’. This includes a guide to creating an effective feedback culture, because the degree to which students give and receive constructive feedback in their lessons is one of the important factors identified by Hattie. This does not just mean filling out a questionnaire at the end of the year for the students to ‘rate’ their teachers. “It’s not about feedback that goes in just one direction”, says Kathrin Pirani, an English teacher who is also a researcher in Beywl’s group. It’s about evaluating the momentary learning environment and about making meaningful changes for the future.

Another instrument that is intended to help teachers improve their tuition is called ‘Luuise’. It’s the German acronym for ‘Teachers teach and assess in an integrated, visible and effective manner’. Luuise guides teachers into investigating concrete problems in their own tuition, testing measures to help solve those problems, and using data acquisition to evaluate whether the measures used have had a positive impact. It helps establish evidence-based curriculum development, says Pirani, who runs in-service Luuise training courses for teachers five to six times a year. “The teachers can keep track of how their teaching develops, and they can focus on what their students need to make progress”.

Research without feedback

But it is difficult to get these tools to the teachers. The researchers offer an in-service training course for Luuise, and some 800 teachers have attended thus far, some of whom have also begun using the method at their schools. But in Switzerland alone, there are more than 40,000 primary school teachers. Luuise has only reached a small minority, but the researchers are pressing on. “We publish articles in journals for teachers and are carrying out pilot projects in schools in order to test these instruments and to disseminate their use”, says Beywl. There are also plans for Luuise to be introduced more and more at universities of education. It is already in use in the teaching methodology courses for English and French at the Bern University of Education, and other subjects are to follow.

Nevertheless, on his difficult quest for schools to participate in his projects, Beywl has noticed that there is a gap between research and practice. “I see an increasing reluctance among schools to participate in data collection”. He can understand this, because monitoring has been greatly expanded in the past 20 years, without the schools themselves gaining anything useful from it. This is because large-scale data collection exercises involve anonymising the data collected – such as the Pisa Studies or the national Swiss project ‘Verification of basic skills’ (called ‘ÜGK’ in German and ‘COFO’ in French). This means that the schools themselves do not find out how they rated. Rankings are created for whole countries, “but the schools themselves get no new knowledge from it whatsoever”, says Beywl.

Beat A. Schwendimann is of the same opinion – he works at the umbrella association for Swiss teachers, ‘LCH’: “It’s not just the large-scale external surveys like Pisa that fail to give schools any useful feedback. The same is true of the many research projects organised by tertiary education institutions in Switzerland”. Schwendimann is convinced that this will have to change. In his opinion, it would be ideal if a commitment to communicate results in an accessible manner were an integral part of research projects, right from the start. He believes that researchers could set up a kind of points-based system, in which points would be awarded not just for the publication of results in specialist journals, but also for knowledge transfer – such as publishing articles in teachers’ magazines, holding workshops, or making specific instruments available to schools.

Moser is also convinced that additional efforts are needed to bring research into the schools, and to get schools to work in an evidence-based manner. For his part, he conveys the results of his studies to the participating schools, and does so on several levels. He shows them how his findings might be used in school development, and also how the teachers might make personal use of them. And just like his colleague Beywl, he is developing tools that teachers and students will be able to use directly in order to learn from his data. Such as the software Mindsteps, which helps to make learning progress visible. Moser says: “If a tool is made easily accessible and useful, teachers are very interested in using it to acquire more knowledge themselves”.

Politicians discuss things differently

The education authorities and politicians also have a major influence. They ultimately decide how the school system looks overall. However, Beywl believes that school authorities and politicians take too little notice of the findings of education research. Instead, they quibble about all the wrong things, such as the great structural debates of recent decades, including discussions about streaming children with different performance levels. “We know from Hattie that having different performance levels hardly has any impact on the learning outcomes of students”. It would be far more sensible in the future, says Beywl, to find ways of reducing the workloads of teachers, thereby freeing up worktime that could be devoted exclusively to curriculum development. Teachers could use this time to apply findings from research, to develop their own teaching using evidence-based means, to work with experts from education research, and to help design tools for data collection. It would be time they could actually devote to improving their teaching.