Feature: Toxic world

Quicker, more comprehensive and more reliable

It’s almost impossible to analyse the many synthetic materials found in the environment. Nevertheless, three Swiss research groups are trying to do just this. They have meanwhile found ways and means to process the immense numbers involved.

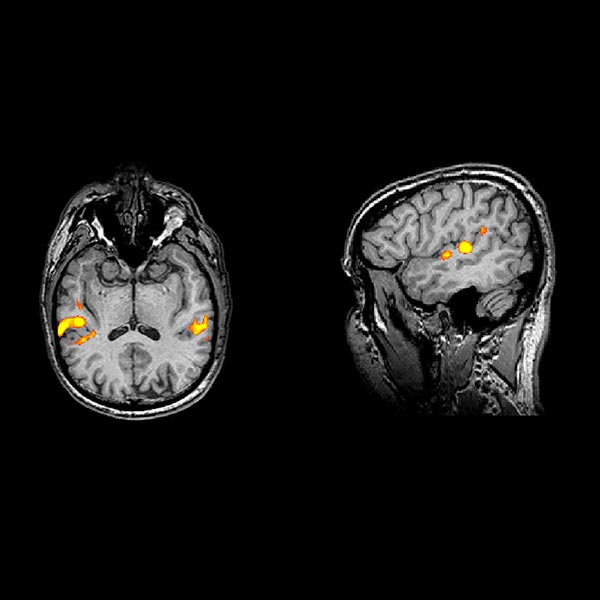

COLLATING EVERYTHING IN A COMPUTER

Shana Sturla, ETH Zurich

The problem: At present, toxicological tests function as if in a black box. We measure only what comes out at the end, not what happens along the way.

The solution: Sturla’s team analyses where chemical substances attack on a molecular level, right down to the tiniest detail. Systems toxicologists like her collate the results of many experiments in computer models. This enables them to cover the whole spectrum of possible interactions. “If we can understand how chemicals intervene in biological processes, then perhaps we’ll be able to predict how toxic they are without recourse to animal tests”, she says.

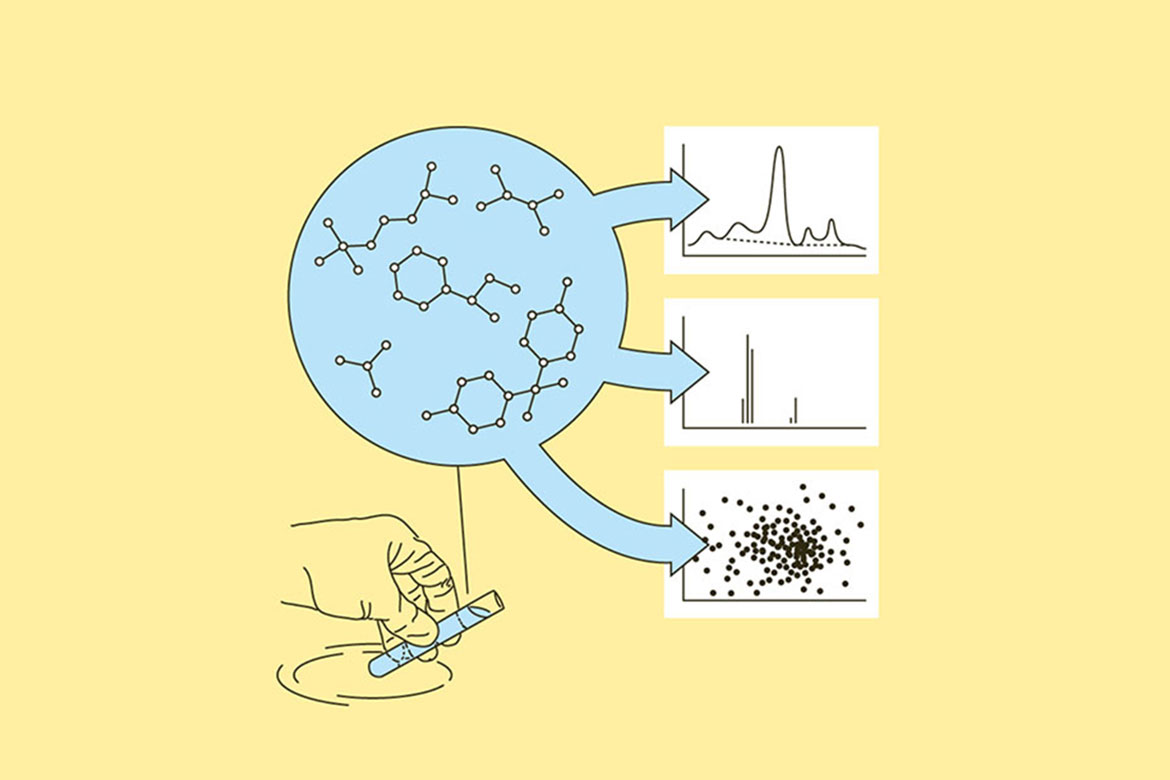

MEASURING STREAMS

Juliane Hollender, Eawag Dübendorf

The problem: No one knows what chemicals are to be found in our waters, because only a limited number of substances are monitored specifically.

The solution: Hollender is an environmental chemist. Using a combination of different analytical techniques, she is trying to detect all the substances in a water sample. She does this using procedures such as mass spectrometry and chromatography. Many of these substances can then be identified using a large chemical database available on the Internet. “This gives us a better picture of the entirety of the substances in a body of water”, she says. And sometimes, the characteristics of those substances can offer clues as to their toxicity.

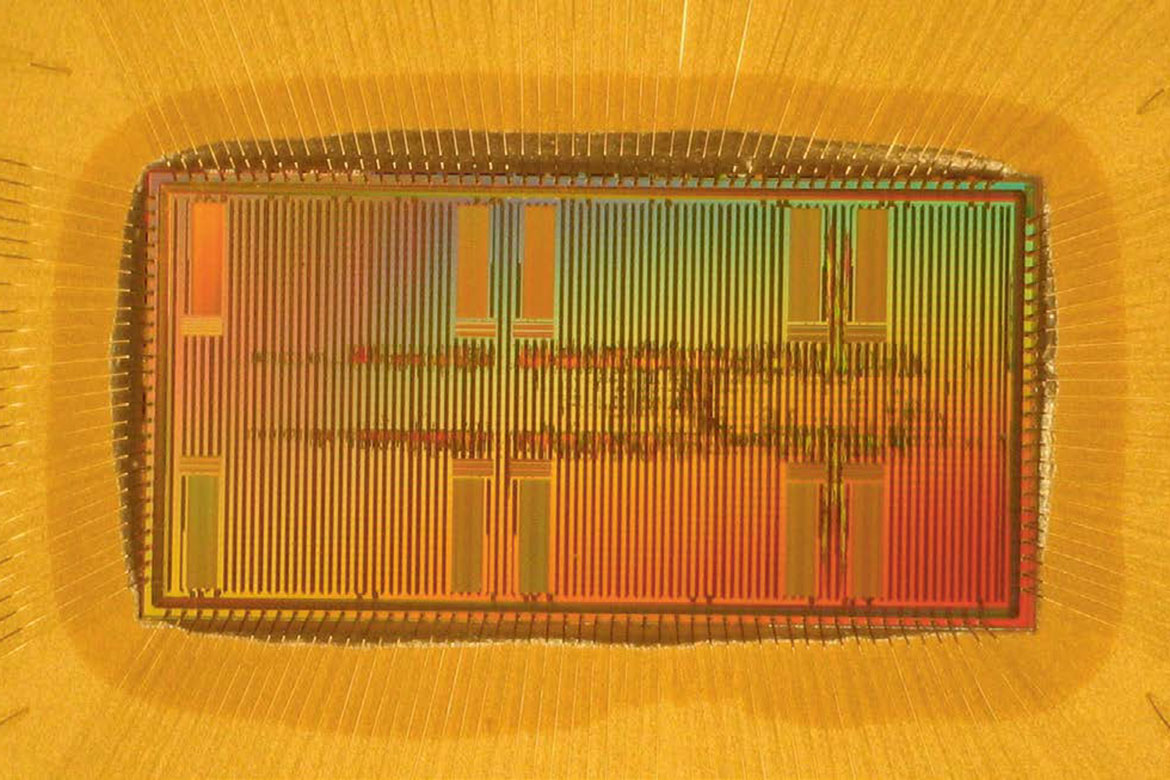

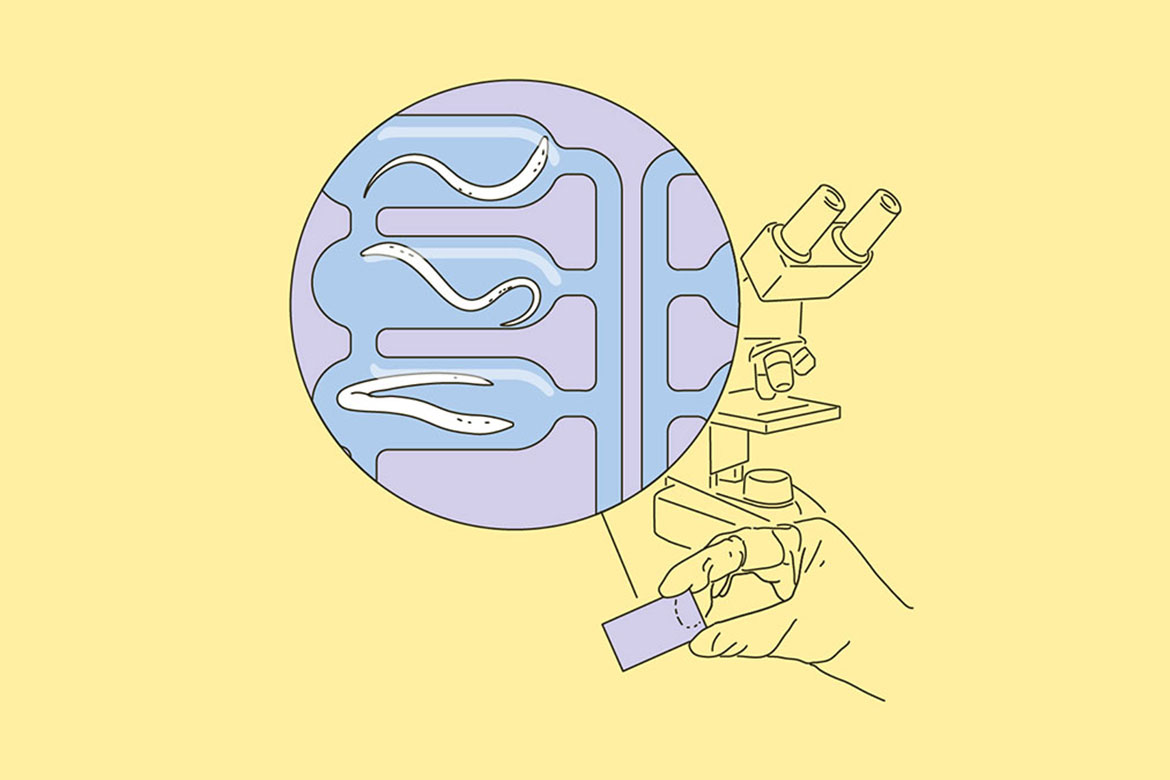

ROUNDWORMS ARE MORE EFFICIENT THAN MICE

Matteo Cornaglia, CEO, Nagi Bioscience, Lausanne

The problem: Testing every new substance costs time, money, and the lives of many mice and rabbits in laboratories.

The solution: The roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans is just one millimetre in diameter, and is a well-investigated model organism. In many ways, it functions like a human being. The EPFL spin-off Nagi Bioscience is developing a procedure for efficient toxicological tests using these worms. In contrast to tests on cell cultures, theirs provide information on the effect of a substance on the whole organism. According to Cornaglia, “this way, we can observe the effect of a chemical over the whole life span of the organism, which is only two weeks”.

Illustrations: 1kilo