Feature: Toxic world

“Unfounded fears only disappear after one or two generations”

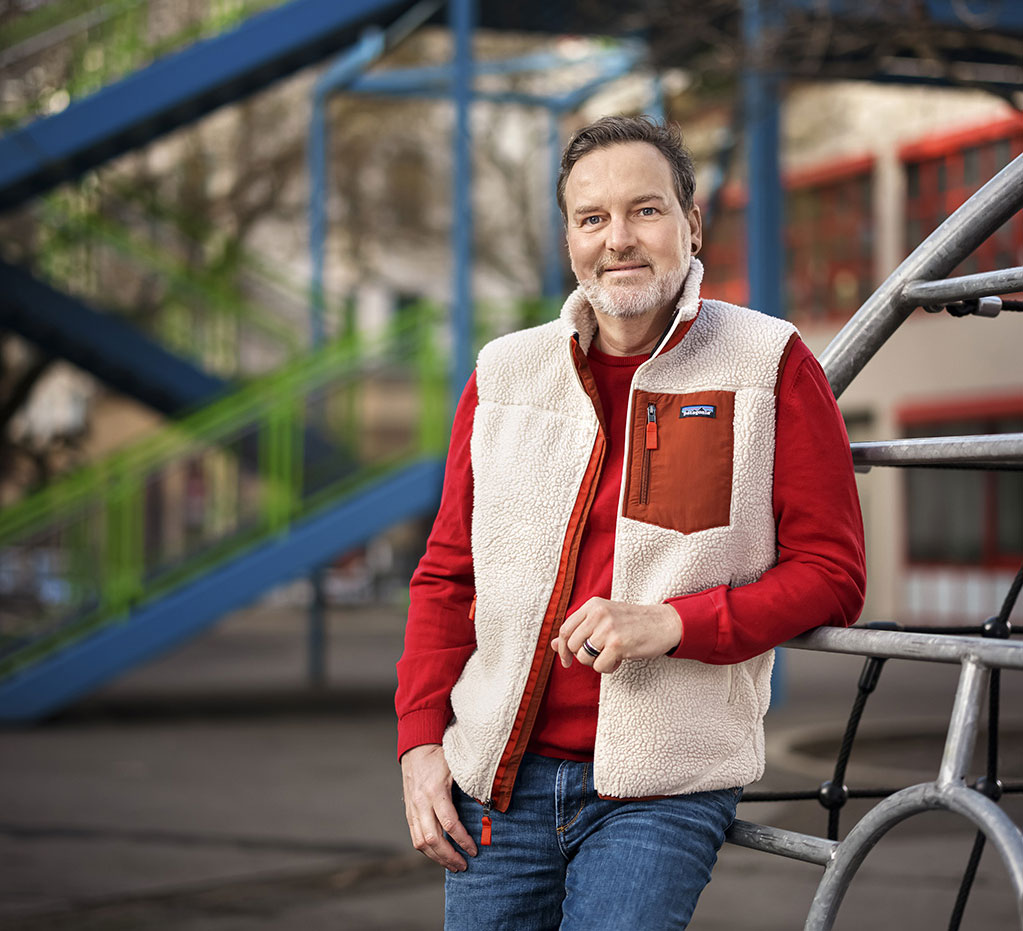

Michael Siegrist is investigating why people sometimes fear things that aren’t dangerous, while not fearing things that are. In our interview, the professor of consumer behaviour at ETH Zurich explains how to communicate risks fairly.

Everything produced by humans is regarded as being far riskier than what Nature makes, says Michael Siegrist. | Image: Valérie Chételat

Michael Siegrist, in September 2019, cantonal chemists found pesticide residues in the drinking water of 170,000 Swiss citizens. This announcement prompted 1,000 angry comments from the readers of the daily paper ‘20 Minuten’. Why?

Water is regarded as something natural and unprocessed. It’s a product of Nature, so we expect it to be pure. If something like that turns out to be contaminated, we find it especially disturbing.

But the contamination is so miniscule that consuming it is harmless.

Yes, to be sure. But those comments came from everyday readers, not from toxicologists. And laypeople don’t pay any attention to the dosage. They tend to an all-or-nothing mentality. The idea that something can be both contaminated and yet harmless at the same time is something that seems inconsistent.

And yet hikers in the mountains will willingly drink from a stream that could be contaminated with animal faeces or liquid manure from farms. Why aren’t they afraid of contamination?

It’s always a matter of what’s being contaminated and by what. Synthetic chemicals are perceived as something bad. But if something is natural in origin, it’s good.

Why does the natural world have such a positive reputation?

In the Western world, Nature is seen as something absolutely positive. We see it with solar power too. It has almost no negative associations. It’s also true that many natural risks are no longer relevant today.

Such as?

150 years ago, people sometimes had to eat food that had gone rotten – and they died because of it. In Switzerland, far more people also used to die in natural catastrophes. But today these dangers are largely a thing of the past. It’s ironic that this positive development hasn’t increased our enthusiasm for research and technology. Because ultimately, it’s thanks to technological innovation and scientific discoveries that Nature is able to enjoy its good image today.

So how did chemicals end up with such a bad reputation?

Everything that is produced by humans is regarded as being far riskier. What’s more, synthetic chemicals are laden with a negative image. They make us think spontaneously of the big chemical accidents like the Sandoz chemical spill in Basel back in 1986 or the Bhopal catastrophe in India. People tend to focus more on the negatives than on all the positive things that chemicals do for us.

Why are we more afraid of small, invisible dangers like pesticide residues or additives in food, and less afraid of the big, obvious dangers like driving a car or smoking?

It’s a question of their usefulness. If you smoke or drive, you have a direct benefit from them. That makes you willing to accept a degree of risk. It’s different with pesticides in our water supply. The consumers don’t see any direct benefit any more. In other words, benefits and risks have been decoupled from each other. The farmer needs pesticides in order to produce enough food for the population, but this benefit is too far removed from the topic of drinking water.

Are there cases where the opposite is true – invisible dangers that we generously choose to ignore?

That’s the case with radon gas, which emerges spontaneously underground. Many people find it difficult to understand how Mother Earth can suddenly produce something dangerous like that. And it’s also a complicated matter. There are big differences in radon emissions from one region to another. You’d have to carry out your own measurements at home in order to know whether it’s necessary to take any action. And people don’t like doing that. This is why the problem is often simply ignored, even in those regions with a high danger of radon radiation.

When it comes to medical applications, we often switch off our fears of radiation, gene-editing technology and chemicals. Why are we willing to accept that?

We’ve long known that sick people will do anything to prolong their lives. We simply want to survive, and that makes us willing to accept anything, to swallow anything, and to put up with a lot of things.

But even healthy people are happy to ingest vitamin C that is produced using genetically altered bacteria.

Most people aren’t even aware of that. And we’re also focussed on the benefits. We don’t want to get sick, and have a clear goal in front of us – staying healthy. What’s more, people assume that when a doctor prescribes a drug, he only wants the best for them. The patients themselves don’t engage so much with the risks or the possible side effects.

Can fears also disappear again?

Yes. But it often takes one or two generations. We can observe this very well in the case of microwave ovens. Forty years ago, the general public was very uneasy about the safety of them. Today, you’ll find one in just about every kitchen.

We can observe the same trends with other, earlier technologies. When the first cars came onto our roads, someone had to walk ahead waving a flag to signal that something dangerous was on its way. The more we become accustomed to something, the better we’re able to accept the concomitant risks, and we then don’t even ask about them any more.

Time and again, we see bouts of hysteria whenever a researcher or an organisation like the WHO publicises the risks involved in drinking coffee or eating meat or eggs. They issue statistics along the lines of: ‘This can increase the risk of cancer by 10 percent’. As consumers, we’re pretty much at a loss as to what all this means. How can we communicate risks fairly without stoking unnecessary fears?

There are two pieces of advice you can take to heart in this instance. First, you have to assess relative risks. You have to compare ‘new’ risks with known risks. In other words: What is the additional, relative risk of getting bowel cancer from eating a certain amount of processed meat, compared to the risk involved in drinking a glass of wine? Secondly, we should always communicate absolute risks. It does no good to say my risk of bowel cancer increases by 10 percent if I eat 20 grams of processed meat each day. I have to know how many people get bowel cancer in absolute terms. Let’s take a hypothetical example. There’s a big difference if 10 people are at risk of dying each year or 100,000, even if the relative risk in each case is 50 percent more. A 50 percent risk makes 15 people instead of 10; that kind of risk wouldn’t bother me. But a 50 percent risk applied to 100,000 people means 150,000 falling ill. That’s a risk I would find relevant to me.

A lot of the risks we hear about in the media are in fact quite harmless. Why don’t scientists or the authorities communicate these things better?

Researchers and the authorities are hesitant about declaring anything risk-free. They don’t want to be accused later of having led the population into a false sense of security. But I personally think they are more cautious than they need to be. In the case of drinking water, you can say with a good conscience that right now it’s harmless to the consumer.