Criticism of animal experimentation commissions

Cantonal commissions examine every application for research involving animal experiments and give advance notice. Their work is sometimes criticised: do they accept too many projects or, on the contrary, do they block authorisations? We lay out the positions of a range of experts.

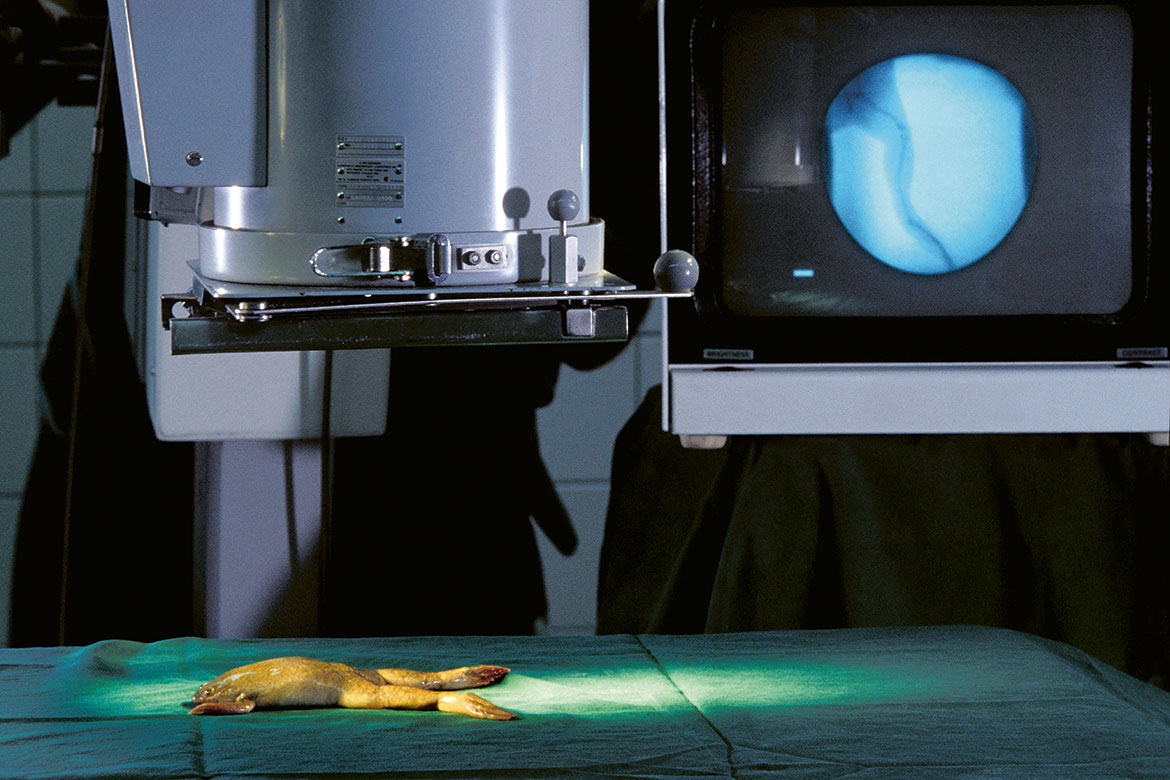

An X-ray analysis of an African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis), a popular test animal for researching into the development of embryos. | Image: Keystone/Science Photo Library/Patrick Landmann

In November 2019, more than 64 percent of Geneva residents rejected the initiative “for better control of animal experimentation”. The initiative had been launched by the Swiss League against Animal Experimentation and for Animal Rights (LSCV), which sought to change the way the canton’s animal experimentation commission operates. Although the Geneva initiative gave rise to much debate between supporters of the current system and its opponents, it was not the first time that the work of these commissions had been criticised. The commissions are typically composed of about ten members coming from the fields of research, animal protection and ethics and from legal organisations. Their mandate is to study the applications submitted by researchers and to issue a notice to the cantonal authorities. In most cases, it is the cantonal veterinary service that is responsible for making the final decision.

So what is wrong with these commissions and their consultative status? “They are alibi commissions”, says Luc Fournier, who was behind the Geneva initiative. Fournier is the president of the LSCV and was a member of the Geneva commission until 2017. “Representatives of animal associations are in the minority (editor’s note: two of seven in Geneva) and can never impose their point of view”, he says. This opinion is contradicted by the biologist Denis Duboule, who is a professor at the University of Geneva and EPFL: “The work of the cantonal commissions is useful. These bodies act as interfaces between scientists and the public. They give researchers a sense of responsibility and force them to listen to what society has to say. They play a significant preventive role: one only has to look at the extraordinary progress made in the treatment of laboratory animals since they were set up at the end of the 1990s!”. Fournier does not deny these developments: “There are certainly horrors that we no longer see, such as animals being skinned alive. But there are still too many absurd projects slipping through, and the commissions almost never reject projects”.

Too many positive notices?

Between 2012 and 2018, the Geneva commission awarded 581 applications a positive notice. It turned down 14, and 70 percent required further details to be submitted. Similar trends can be observed in the other cantons. “Few projects are refused”, admits the bioethicist Samia Hurst, who is a professor at the University of Geneva and a member of the Geneva commission. “But is it a sign of dysfunction? To me, it shows that the researchers know the legislation”. Hurst points out that these commissions serve to bring different actors face-to-face to assess the compliance of applications with the current legal and ethical framework. Their role is then to decide whether it’s worth the candle: do the expected benefits of the research justify the suffering of the animals? This weighing of interests is at the heart of their work. “In this context, I understand that it would be difficult for someone to be on the commission if their personal aim is already the abolition of animal experimentation”, says Hurst. “Because in the end, the law allows it”. The Zurich cantonal veterinarian Regula Vogel, whose office either approves or rejects research using animals, also explains that the cantonal law on animal protection prescribes a diverse composition of the commission. However, she points out that its members “are not elected as representatives of their respective institutions, but on the basis of their expertise. In holding this office, they must be independent of any entity or authority”.

Another criticism sometimes levelled at the work of the commissions is that the experts are overwhelmed. “We have to deal with about 600 requests a year”, says Vogel. “But it’s part of the commission members’ mandate to have enough time to evaluate them. Furthermore, only those applications involving severe animal suffering are systematically referred to the full committee, while the others are assessed by sub-committees”. Other voices also consider that the committee experts might not have the necessary know-how to assess the quality of the research projects submitted. Duboule agrees with this criticism: “A scientific assessment can only be legitimate if it is carried out by peers. A commission of about ten members will never bring together enough disciplines. If this were the aim of animal experimentation commissions, then indeed, they would not have enough resources. But I don’t think it is”.

Debate on the right of appeal

In Switzerland, only the Zurich commission has a right of appeal, and only when at least three of its members jointly oppose a majority decision. This right has been exercised nine times in fifteen years, almost always for experiments on primates. Fournier’s initiative would have given a right of appeal to each of the seven members of the Geneva commission: “This would have strengthened the power of the members representing animal protection associations and given the commission more clout”. During the Geneva campaign, opponents told him that this would block the authorisation process and ban animal research in practice. The case of Valerio Mante of the Institute for Neuroinformatics at the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich could prove them right. In 2013 he submitted an application to conduct research on three monkeys. The application was accepted by the cantonal commission but was subsequently appealed. The procedure usually lasts three months, but it took Mante more than three years to win his case – that’s the amount of time normally required to write a doctoral thesis. But couldn’t the right of appeal nevertheless act as a kind of safeguard, allowing the representatives of animal associations to be heard in certain cases?

For Hanno Würbel, a professor of animal protection at the University of Bern, it is not the most effective tool, as it tends to create a tense climate between researchers and animal advocates. “These tensions do not benefit animal welfare. What benefits them is the further training of researchers, the application of the 3Rs principle (‘Replacement, Reduction and Refinement’) and good management in research institutions. There has certainly been a lot of progress in recent years, but I believe that there is still room for improvement inside institutions. And they will only do so if they are put under pressure”. Instead of introducing rights of appeal for committee members, Würbel considers that “another solution would be to limit the expectations we place on the commissions. In order to play their role as an interface between science and society, their main task would be to assess the balance of interests proposed by researchers. On the other hand, good scientific and ethical practices within the institutions should be strengthened, as well as support for them to hire more qualified staff to manage animal houses”.