Feature: Belief in science

“It’s a dilemma for the science historian”

Although everything seems to place science and belief in opposition, in reality, the barrier between them is far from watertight. The science historian Michael Hagner, whose background is in medicine and philosophy, sees not only a problem but also an opportunity.

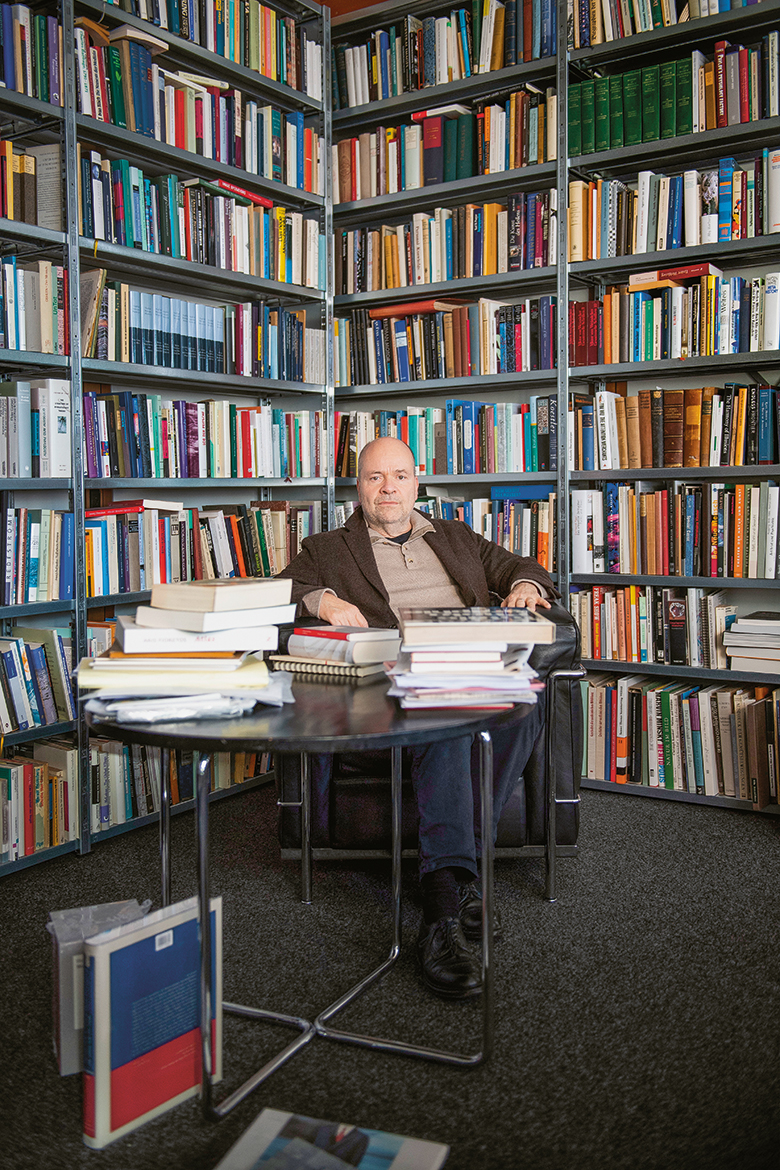

“Beliefs can drive new ideas and contribute to the exploration of territories that the mainstream finds irrelevant.”, says Michael Hagner of ETH Zurich. | Image: Valérie Chételat

Do beliefs play a role in the history of science?

I would distinguish between two types of belief. The first is commonplace: the trust that each scientist places in the results of others. Since we cannot reproduce all the experiments we read about, we rely on the belief that the methodology and data of our colleagues are correct. This trust, without which science could not function, must be distinguished from religious, cultural, political and social beliefs. This second category has also played a role in the history of science, with both positive and negative effects.

For the history of neuroscience, a particularly harmful belief has led to the attempt to locate categories such as gender and race in the brain. This used the authority of neurologists to justify the assertion that women are inferior to men and non-Europeans to Europeans. These ideas are no mere accident in the history of neuroscience, but have guided research since the late 18th century. The measurement – or mismeasurement, to use Stephen Jay Gould’s term – of skulls, brains, cortical convolutions, and the cytoarchitecture of the cortex was intended in part to measure supposed intellectual and moral differences between the sexes and among races. The traumatic experience of the Holocaust has led neuroscientists to reflect further on their own beliefs. But scientists of each new generation must undertake this thought process. Today’s neuroscientists should be aware of the pitfalls of the past and be cautious in their assertions.

Is today’s neuroscience free of such beliefs?

No. The notion of race was largely abandoned in the late 1940s and early 1950s. But when it comes to sex and gender, the situation is more complicated. Some neuroscientists still believe that there are cognitively and psychologically significant differences between male and female brains, while others categorically reject this notion. The idea that such a difference does not exist is, if you like, also a belief, linked to fields such as ‘cultural studies’ and gender studies. But research shows it is very difficult to identify a typically male or typically female brain, or to use observational data to infer the existence of a particular set of cognitive abilities.

Sometimes science is reluctant to question a belief, for example in the case of free will ...

The debate on free will in the neurosciences came in the wake of Benjamin Libet’s 1983 experiment, widely interpreted as a demonstration that free will does not exist. And outside of this experience, philosophy had long been questioning the concept. But the notion of free will is proving to be extremely resistant. Why is it so resistant? Because it is socially useful in giving meaning to our lives and to the world. The latter idea has been taken up by neuroscientists who have turned it into a Darwinian argument, claiming that our brains use ideas, true or false, to improve our ability to survive, and that our belief in free will has been selected because it serves an evolutionary purpose. But I’m afraid this position is not supported by any scientific evidence. It is nothing more than a belief.

So science will never truly free itself from belief?

So far, we’ve talked about the role that beliefs play in science, and it’s essential to be aware of it. That said, it is important to note also that science has developed powerful tools to combat prejudice through the development of what is the most reliable system for producing knowledge. Of course, the system is not perfect. It can fail, which makes most scientific results both reliable and tentative. Moreover, scientists themselves sometimes work with beliefs, conscious or otherwise. And there are powerful forces in today’s societies that are preventing science from being accepted as the most reliable source on issues such as climate change and its anthropogenic nature. This last point complicates the discussion. From a historical and epistemological perspective, we inevitably come to the conclusion that science is not free of beliefs. But if we say this in a political context, it is easy for climate deniers and other fundamentalists to take this statement and use it for their own purposes. This is the dilemma that historical epistemologists like myself face today.

At the beginning of our interview, you mentioned the positive impact of beliefs in the history of science. What are those positive effects?

Beliefs can drive new ideas and contribute to the exploration of territories that the mainstream finds irrelevant. In other words, beliefs can make the scientific system more complex and interesting. If the system is too rigid and impenetrable, it sooner or later becomes unproductive.

The term ‘pseudo-science’ is used as a convenient way of distinguishing legitimate knowledge from beliefs disguised as science. About ten years ago, you argued against the use of this notion. Seeing the extent to which the current digital environment provides a sounding board for pseudo-scientific beliefs, have you changed your mind?

In my 2008 study that you mention, I argued that philosophers and scientists have not been able to draw a clear line between science and pseudo-science. Today, the shift to digital communication and social media makes it more difficult to distinguish between knowledge that is relevant and sound, and the dross that is neither. It’s a big problem, but I do not think that the epistemological category of pseudo-science is useful to solve it. We need to analyse and explain in detail the categorical differences between reliable knowledge and waste material. Also, there should be restrictions on the power of the global digital platforms, the so-called ‘Gang of Four’, comprising Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon. Their monopolistic power has become so disturbing that it increasingly resembles a totalitarian system.