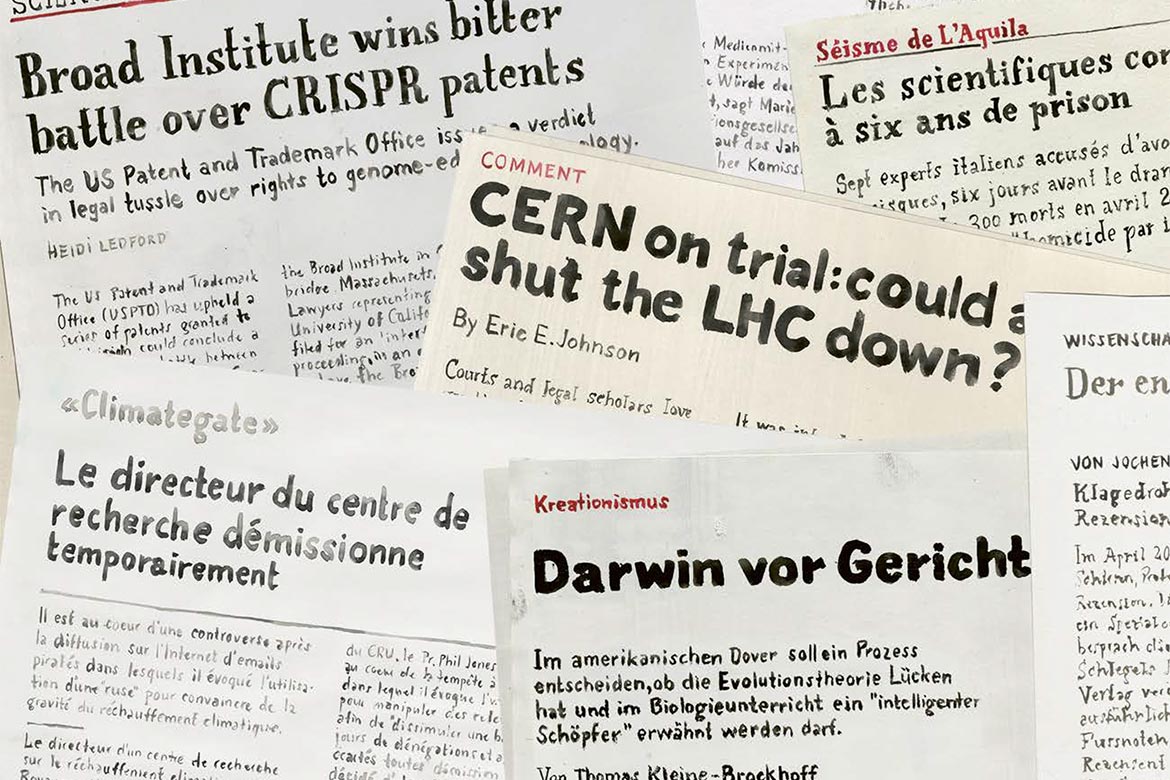

When justice gives short shrift

In Switzerland, nine out of ten sentences are no longer handed down by a court, but directly by the state prosecutor as ‘summary penalty orders’. This curtailed procedure takes the strain off the justice system, but new research is raising constitutional questions.

Going straight to jail by penalty order, with no court proceedings. This is possible in Switzerland, but is criticised by legal experts. Here we see an individual cell in the regional prison of Bern. | Image: Valérie Chételat

The accused stands before the court, his defence attorneys at his side, engaged in verbal sparring with the state prosecutor in a battle about guilt and innocence. At least that’s how many people imagine the courts to work. But everyday justice in Switzerland is usually much more matter-of-fact, with the ‘classical’ criminal trial an exception. Nine out of ten sentences are today issued as summary penalty orders. That’s a lot more than was the case twenty years ago. In other words, the state prosecutors deal with such cases directly, and largely in writing. There is no in-depth examination of the issues, and there are no court proceedings.

Instead, those affected are sent a suggested sentence by post. They then have ten days to appeal against it. If they don’t, “the supposition of guilt by the state prosecutor automatically becomes a guilty verdict”, says Marc Thommen, a professor of criminal law at the University of Zurich. These so-called summary proceedings have one great advantage: they free up the justice system. Petty offences that occur in high numbers – such as traffic infringements – can be dealt with quickly. Even offences against the Aliens’ Act can be managed swiftly, as can offences that are classed as minor or moderately severe by the criminal code, such as shoplifting or affray.

Prosecuting judges

The Swiss justice system issues 120,000 sentences every year – not counting minor infringements that are dealt with by means of mere fines. If it weren’t possible to issue summary penalty orders, the justice system would simply collapse. And many a wrongdoer is perfectly happy if he does not have to appear in court. Accepting a penalty order is more discreet for the accused, and it costs the state less time and money. A new criminal procedure code was introduced in 2011 to unify the system across all of Switzerland. But there are experts in jurisprudence who have long been critical of these swift proceedings.

Marc Thommen is running a research project about them. He finds it especially problematic that there is such a concentration of power in the hands of the state prosecutor, because he is essentially the prosecutor and the judge at the same time. “This means we are abandoning the separation of powers, which was an important achievement of the Enlightenment”. The use of penalty orders is more prone to error, because evidence is not sought as thoroughly. And they limit the rights of the accused. If someone gets a penalty order, they can raise an objection, but really this happens in just a few cases. What’s more, it’s rare for a disputed offence to land before a neutral court for judgement. This is proven by surveys that Thommen has carried out together with researchers at the University of Neuchâtel.

Analysing thousands of penalty orders

The research teams analysed a total of almost 4,700 penalty orders in the cantons of St. Gallen, Zurich, Bern and Neuchâtel. This sheer abundance of data has not yet been properly evaluated, though initial insights can be gained in the case of St. Gallen. They show that less than ten percent of those affected raise any objection. And what happens afterwards is also determined by the state prosecutors. They stopped proceedings in just under 15 percent of the cases analysed in St. Gallen. In roughly a quarter, the prosecutors issued a different penalty order. Cases only landed before a judge in 20 percent of the (already very few) cases in which an objection was raised.

Can this low complaint rate mean that the guilty accept their penalty and regard the proceedings as fair? Thommen thinks that this is possible. But he nevertheless sees a whole host of possible other reasons. Perhaps there are language problems, because the penalty orders are not translated. People with reading difficulties might feel swamped. Others might not get the order in time because they are out of the country. It is even possible that innocent people might decide not to use their right to object because they fear negative consequences. Thommen offers an example of a teacher who is wrongly accused of consuming illegal pornography. “If he insists on objecting to the penalty order, then the case becomes public, and that would mean the end of his career and his reputation”.

Go straight to jail

The state prosecutors can use penalty orders to issue fines and other financial penalties, but also prison sentences of up to six months. Most of the cases analysed in St. Gallen ended with fines. But in one out of 14 cases, the state prosecutors issued a prison sentence, usually not suspended. What’s more, in only ten percent of cases did the state prosecutors actually speak to the accused before sending out the penalty order. In all the other cases, the judgement was based on the documents to hand. And only just under seven percent of all people accused took a lawyer. If people are being sent to prison for months after a minimum of investigation, without any hearing, without legal counsel and without a judge, then this is a precarious state of affairs, says Thommen. These are not the petty cases for which the penalty orders were originally conceived.

As for interrogations, the state prosecutors are free to listen to an accused person or to base their decision on the police investigation. As a rule, this depends on whether or not more information is needed about the circumstances of the case, says Nora Markwalder, an assistant professor for criminal law at the University of St. Gallen. But asking the accused questions in person can also fulfil further functions. “It allows them to participate in the process”.

Ensuring fairness

Markwalder is now investigating the impact of penalty orders with and without interrogations. For example, she is looking at the duration of proceedings and the probability of objections being raised. She still has only a small amount of data. “Our goal is to be able to offer cost/benefit analyses of the interrogations”, she explains. This is because the cost effectiveness of the procedures is important to the legal authorities – a matter that is underlined by the sociologist Mirjam Stoll in her doctoral thesis at the University of Basel. Stoll says the way the authorities deal with criminality “is guided by neoliberal principles”. Much of the responsibility is delegated by the justice system to the accused themselves, as they are the ones who have to decide whether or not to raise objections. “That is in line with neo-liberal demands for more individual responsibility, and has less to do with any notion of public assistance”. Stoll believes that this can lead to social inequality. Those who are less well-educated, less well-off or who don’t speak the local language as their mother tongue are less likely to raise objections than someone who can understand the specialist jargon of the penalty order or who can afford a lawyer.

However indispensable the penalty orders might be in practical terms, “they have to be organised fairly”, insists Marc Thommen. What’s more, Switzerland has duties under international law. He believes that one means of making things fairer would be to establish a duty to examine the accused. It is precisely just such a correction that the Federal Council is now proposing in its partial revision of the criminal procedure code. The state prosecutors should in future be compelled to listen to the accused before issuing non-suspended sentences. The National Council will soon be dealing with the draft law.

For Thommen, there is also the question as to whether the justice system could cope with its mountain of work by better means than pushing for increased efficiency. Such as by decriminalising minor offences or by simply shelving petty acts of wrongdoing. The Swiss have a relatively pronounced desire to see punishment meted out, says Thommen. So there is much to debate here, both in parliament and in society. Thommen isn’t going to give up either. The “broad mass” of people receiving penalty orders has thus far been too little investigated. There aren’t cases of large-scale, spectacular criminality. But what’s at stake are fundamental legal procedures and constitutional guarantees.

Experts in jurisprudence are asking legitimate questions about penalty orders and their procedures – this much is accepted by Baschi Dürr, a member of the Free Democratic Party in the government of the canton of Basel-Stadt and the canton’s head of justice and security. “We can talk about these things, but we have to keep a balance between what’s desirable and what’s practically possible”, he says. As far as the cantons are concerned, the procedure has proven itself. Experts in penal law are recommending establishing a duty to examine the accused, and this is now also being proposed for certain cases by the Federal Council (see the main text of the article). But this goes too far for the cantons’ liking. They fear they will have to pay considerable extra costs, and would prefer to find a compromise. “Somewhere between constitutional perfection and cost-effective pragmatism”, says Dürr. He does not regard the penalty orders as “unfair”, because those accused can still object to the proposed sentence.