The meaning of vomit

Ants feed each other a regurgitated liquid. This lets them exchange information that’s important for the well-being of their whole colony.

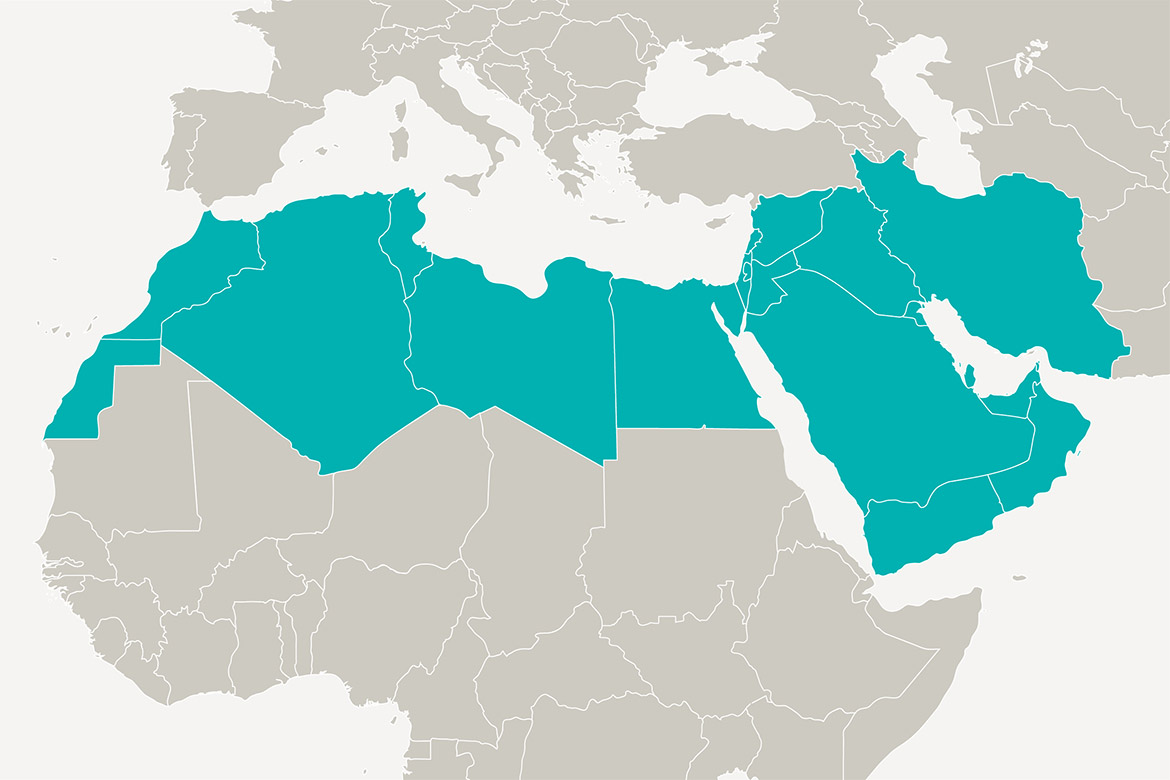

A social network for ants: They exchange information about food sources and the growth of their young by sharing regurgitated liquid. | Image: Rakesh Kumar Dogra/Wikimedia Commons

Ants don’t just share their work, but their food too. They regurgitate a drop of liquid food from their social stomach that is like nectar or honeydew, and pass it on to their fellow ants by mouth-to-mouth contact. This phenomenon is called ‘trophallaxis’, and is also practised by other social insects such as bees or wasps. But it’s about more than just sharing calories. This fluid also contains information on the smell and the taste of the food, which helps workers to find its source. Researchers have long suspected that trophallaxis has many other functions too.

A research group led by the biologist Adria LeBoeuf at the University of Fribourg is now shedding light on this issue. Thanks to the great progress made in analytical procedures in past decades, she can now immerse herself in these tiny droplets of food, as it were, and find out just what is in them. She’s slowly finding out about the real significance of trophallaxis. “A complex form of communication is hidden in this fluid”, says LeBoeuf. “But it’s comprised of molecules, not words”. It’s a kind of social network based on vomit.

Fighting infection together

It could, for example, help the ants to ward off diseases. LeBoeuf has found substances in the saliva of the ants that promote immune defences against bacteria, fungi and viruses. “This might function in a similar way to new-born babies who rely on their mothers’ milk to build up their immune system”.

But trophallaxis has the greatest significance for young ants. LeBoeuf’s team has discovered growth hormones in the fluid that stimulate the development of larvae. The female workers alter the amount of growth hormones in the fluid they share, which enables them to regulate the tempo of the larvae’s development.

“This makes the growth of the colony a democratic matter”, says LeBoeuf. “Every ant gets a say in things through the amount of growth regulators in their regurgitated food. Since this food is passed on from one ant to the next, it finally also arrives at the larvae”. In other words, an ant that collects food somewhere in the forest can influence the future size of the whole colony through their social network.

LeBoeuf’s work is prompting a lot of interest among other ant researchers. “It’s very exciting”, says the zoologist Jan Oettler from the University of Regensburg. “But we shouldn’t use it to make generalisations about all species”. This is because trophallaxis is not found among all types of ant. “In some species, the larvae themselves eat and are not provided with a pre-digested pulp”. In those ants, the workers regulate the growth of the larvae using other mechanisms, such as biting. “Then there are species whose development is already predetermined in the egg. In those cases, the workers have no opportunity to control anything”, says Oettler.

Just how the communication mechanisms of trophallaxis function in detail is something that LeBoeuf’s team is trying to find out, using an unorthodox experiment. They are feeding worker ants with fluorescent food that has been enriched with growth regulators. “The more the larvae get of it, the more they glow when we look at them under UV light”, says LeBoeuf. They are monitored by a computer that records the development of every larva with a camera, even when they are moved from one place to another by the workers. “We can now observe how the ants control the development of their larvae, meal by meal”.