In brief: Corona special

The coronavirus hunter

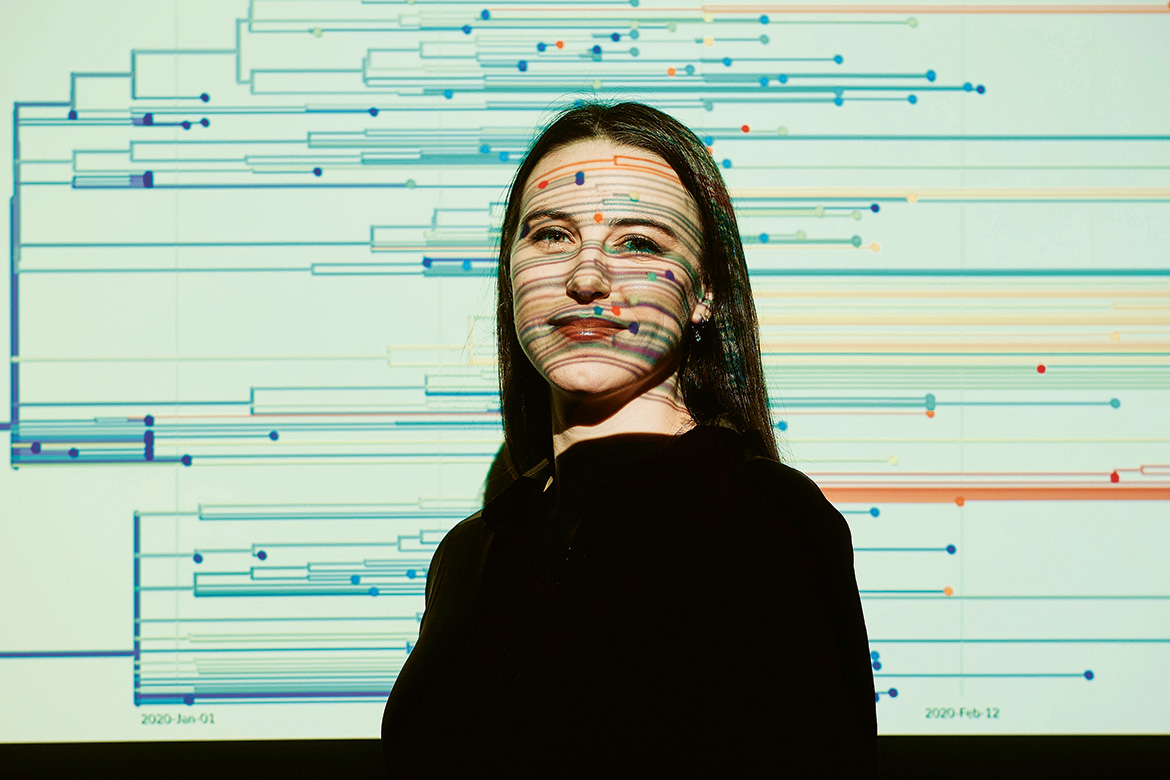

In just a couple of months, the biologist Emma Hodcroft has become one of Switzerland’s most followed researchers on Twitter. She tracks mutations of the coronavirus as it spreads across the world. Whether she’s talking about her own research, or public health and science policy, she addresses complex questions in a precise yet approachable way.

The virus researcher Emma Hodcroft takes time for the media whenever her day-to-day research allows. | Image: Roland Schmid

Her name has appeared in Wired, the Boston Globe and the NZZ, but also in the Aargauer Zeitung, Blick and even Nau, a news platform shown on screens in busses, at petrol stations and fitness centres. This is an impressive feat, because Emma Hodcroft, an American-British researcher working in Basel, does pretty complicated research. She is busy mapping mutations of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in real time. But her straightforward communication style has made her one of the best-known faces of science in Switzerland during the pandemic, along with senior experts. “It was heart-warming to be featured in local media. As a foreigner in Switzerland, I felt accepted and valued”, she says, sitting on a metal chair in a park next to her flat in Basel.

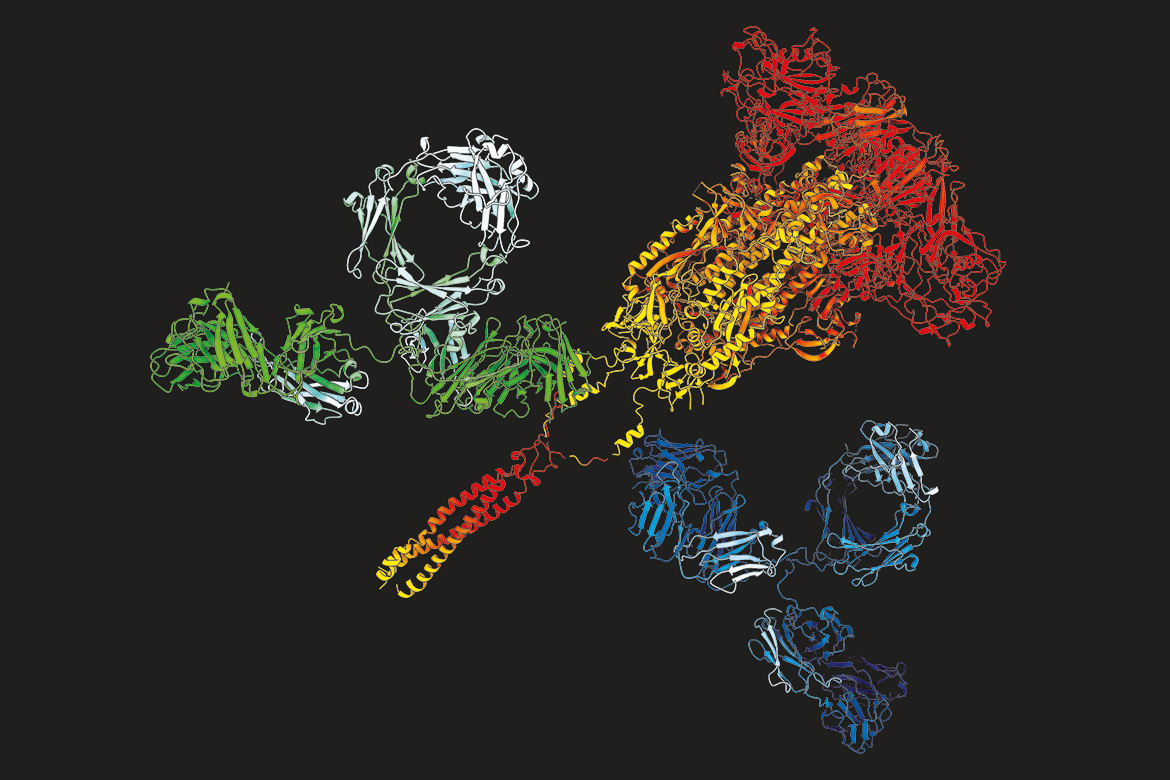

But she regrets that the media sometimes badly misrepresent the genetics of coronavirus: “A mistaken narrative keeps popping up: that some types of SARS-CoV-2 would have different epidemiological properties, such as being more or less contagious according to the population at hand. But this is absolutely incorrect. We’ve compared tens of thousands of virus samples from all over the world, looking at mutations where one genetic letter is exchanged for another. And even the two most divergent mutations have no more than 40 such mismatches out of the 29,000 base pairs that contain their whole genetic information. These are very small differences, and have so far shown no impact on the behaviour of the virus”.

When USA Today gets it wrong

She does not shy away from publicly correcting such misrepresentations, and she uses the opportunity to broaden the debate. When USA Today mentioned “eight strains of the coronavirus” in a headline, she tweeted: “Thanks to your article we are inundated with emails about people very worried about these strains. Every time you decide to go with an alarmist unfounded incorrect headline, you burden already overworked scientists trying to battle #COVID19 with more work trying to calm the panic. We are working so hard – plz don’t make our jobs harder!! Report responsibly”.

Her research showed in early March 2020 that the epidemic in Seattle was fuelled by community-based infections, not by people importing the disease from abroad. Such analyses can be useful in assessing the effect of travel bans and closing borders. “What we see from the genetics is that there were many imports and exports of the virus, into and out of most countries, especially Europe. This shows that by the time the borders were closed, the virus had already spread. It also goes against the idea that just one country infected the others”.

She says she’s aware her research will be politicised, but feels it’s her duty to explain it the best she can. “We always stress the limits of what we know, even if we are aware that this uncertainty might get lost once in the media. We sometimes decide to share preliminary results only with scientists, because the uncertainty is just too great for us to risk it being misrepresented. Our work is very visual, with colourful relational trees and a world map covered with zigzagging lines. This can tempt the media into telling stories that just are not supported by the data”.

Party less, focus more

Emma Hodcroft’s life path is itself reminiscent of just such a map. Born in Norway to parents working in the oil industry, she grew up in Aberdeen in Scotland before following her American mother to Fort Worth in Texas when she was five years old. She spent every summer with her father in Scotland – travelling the first time alone with her younger sister when she was 12. They attended an extra month of school in the UK, because the holidays there were not synched with the US. “We never thought the additional school was odd; we didn’t know any different. And no, I don’t think it made us any smarter!”, she laughs. Despite her rising stardom in the world of research, she insists she was an average student: “My dream had always been to be a medical doctor, but my grades at university in Texas were not good enough to pursue it. I realised then that research could actually be a career, and that people got paid to study evolution, a topic I had been interested in since I was a teenager. This helped me to spend less time reading and playing video games, and more time studying. I also liked computing, which I had learned from my mother and a teacher at high school”.

After completing her studies in Edinburgh, UK, she started researching the genetic evolution of that other famous virus, HIV. She moved to Basel in 2017 to work with Richard Neher, a cofounder of Nextstrain: an open-source project to analyse and visualise phylogenetic trees of pathogens such as coronavirus, influenza, Zika and Ebola.

A stranded researcher working 24/7

“As a scientist, I know a lot about what’s happening in the Covid pandemic, and probably do not have the same worries as most people who feel more uncertainty in the situation. I think I’m a bit shielded from the impact of the current lockdown [April 2020, eds.], because I essentially spend almost all my time working. I work from home on my laptop, sometimes at my partner’s. I start by checking up my emails when I get up at seven in the morning, to see what the Nextstrain team in New Zealand has posted; I catch up with the Seattle team in the late afternoon. I fetch new genomic data posted on international servers, run analyses, check for errors, correct sample metadata such as location or time. We then look for patterns, annotate the graphs, upload to the website and post on Twitter, tagging the lab which has sequenced the virus sample. I finish work at 9-10 pm. I take a few breaks to eat. I do try to take the morning or the afternoon off on Sundays. Altogether, I might be on a sort of high: while the epidemic is really sad, I’m fortunate to be in a position where my work and skills count and do make a difference. This is incredibly rewarding, and motivating”.

Her team is continuously improving the code, in particular to deal with the very high traffic it has attracted as the pandemic spreads. Her research is a perfect example of open science: on the one hand, the data comes from a multitude of institutions across the world that upload genomes sequenced from local viruses on a common platform. On the other hand, all of Nextstrain’s data and analyses are posted online. She welcomes the exchanges that this openness allows: “We get better science if we work together and if we are open to criticism. This remains the best way to improve”.

The science influencer

Hodcroft had 800 followers on Twitter in January 2020. Four months later, she has almost 18,000. “I try hard to do as much as I can because I feel I’m good at science communication. I instinctively started reacting when I saw misinformation. At the beginning, a lot of people were hearing mixed messages, from ‘it’s no worse than the flu’ to ‘well, the situation in China looks worrying’. I wrote a thread differentiating preparedness from panic, because I felt the message was not clearly communicated by governments. My tweets generated more and more reactions, and I realised I needed a system to deal with it: I won’t respond to comments that are mean, rude or loony. But I do give people the benefit of the doubt because I think they might be scared by the disease. I still have to remind myself that I don’t owe anyone an answer on Twitter if I don’t want to. As a young woman rising on social media, I consider myself lucky: I did not experience proper harassment – usually, rude comments or weird pictures are sent only once”.

She says that Twitter has been used a lot, not just to talk to lay people, but also for constructive scientific discussion between researchers about the latest data and analyses: “Usually, researchers communicate by publishing letters in scientific journals. We just don’t have the time for that!”

Money for others

In a noted tweet, Hodcroft highlights a conundrum: special funding schemes for Covid research are great, but might select the wrong kind of researchers: “Those working on #SARSCoV2 *right now* are those least able to write grants!” Currently working some 80 hours a week, she says she would struggle to find the time to fill in grant proposal forms. Many underfunded scientists are in the same situation, she says, but keep adding hours for urgent research on Covid-19. She suggests a completely different way of funding research: “Instead of selecting projects on the basis of what they promise, funders could allocate money a posteriori, according to the output of research which has been already done during the pandemic”.

But does she actually need money for her work? “Not really for myself, because of great support from the University of Basel. But many labs around the world, in Greece or Portugal in particular, cannot buy the reagents necessary to sequence virus samples, which is the genomic data needed by Nextstrain. So I’d like funding to be able to pay them for that”.

During our two-hour conversation, Hodcroft paints an intricate picture of how scientists work, think and feel in times of crisis. She provides clear answers, original perspectives, strong opinions and names relevant sources, but keeps stressing the limits of what she knows.

At 33, she finds herself in a crucial moment in her career. Her publication record now starts to count a lot, and she wonders whether her CV will really benefit from all the time invested in communicating and sharing data. While her work is obviously having an immense societal impact, the latter is not captured by the usual metrics for measuring scientific careers. As of April 2020, her publications had been cited a relatively modest 410 times. “But the greater goal is not me”, she says. “It’s to help the world by understanding it”.