Feature: Getting creative against climate change

Come fly with me

Should we leave the Earth behind us and keep it only as a giant nature park? – or should we use new technologies to influence the climate here as we see fit? These two big visions of how to save humankind from the consequences of global warming raise many ethical questions. We’ve taken a closer look at them.

One day, we might be able to generate electricity like this on Mars. This is the Crescent Dunes Project in Death Valley in Nevada. | Image: Jamey Stillings

“If you want to … save the Earth, we have to go to space”, explained Jeff Bezos in May 2019 when he presented his moon lander in Washington DC. Besides running Amazon, Bezos is also the owner of the space company Blue Origin, and he has pretty clear notions of how to achieve his goals. This decade, his company is going to help NASA to send astronauts back to the moon and set up a permanent base there. From there, the next stop will be Mars. Bezos maintains that both these celestial bodies have resources that we could mine and utilise on a large scale. Ultimately, industry and energy production could be completely relocated into space, and the whole population of the world could be housed in free-floating space colonies. In this way, the Earth could be kept as a natural living environment – a kind of nature park for people to visit now and then.

Incredible arrogance

This vision is testament to a fantasy of omnipotence, says Andreas Brenner, a professor of philosophy at the University of Basel. “What’s more, it’s based on the idea that we could live perfectly well without the Earth”. Brenner specialises in environmental ethics, and he insists that we humans are ourselves part of Nature; we help to shape it, and it in turn supports us and moulds us. If we were in isolation, detached from Nature, we would atrophy. What irritates Andreas Brenner most of all is the “incredible arrogance” that is expressed here. “Here is one man, speaking for the whole of humanity. And what’s more, this is someone who has heavily promoted a way of life that contributes to the destruction of the Earth, and who has earned money from it”. But not everyone participates in the overexploitation of the Earth. “There are billions of people who live very differently. Would they all have to leave the Earth too? And what about our descendants? If we emigrate into space, we will be depriving them of the freedom to decide how and where they want to live”.

These foehn clouds look like they’ve been made by hand, though they are a natural phenomenon. Various projects are being developed to try and make artificial clouds over the sea in order to help cool the climate. But such geoengineering projects are highly controversial. | Image: Pierre-Yves Massot

Andreas Brenner does not regard humans as a fundamentally harmful element that needs to be removed for the good of Nature. “A portion of humanity has caused great damage in the past few centuries”, he says. “But we can solve these problems by adopting a way of life that is not dependent on the destructive consumption of resources”. Brenner sees this as an ethical duty that is derived from principles of justice and responsibility. “We super-rich people are taking so much of the Earth’s resources that there is no longer enough for others. And in order to ensure our present advantages, we shift the damage and the risks involved onto people elsewhere and onto later generations. That is irresponsible”.

Responsibilities will remain on other planets

Anna Deplazes-Zemp is an environmental ethicist who runs the research project ‘People’s Place in Nature’ at the University of Zurich, and she also insists on our responsibilities. There are many arguments to support her. We need Nature and have to preserve it for ourselves, our fellow human beings and future generations. But such a perspective is not enough. “That would mean that it’s actually unproblematic to destroy those ecosystems that do not seem directly useful for humans”. Living things, ecosystems and the Earth all have intrinsic value, and are in and for themselves worthy of protection. Such a perspective is based on “a metaphysical assumption of values”, says Deplazes-Zemp.

But primarily, we bear responsibility because we humans are part of Nature and exist in a multifarious relationship with it. “This special relationship results in values that require a responsible approach to Nature on our part”. This is something we cannot evade, insists Deplazes-Zemp, not even by escaping into space. Because we would have the same set of responsibilities on other planets.

But perhaps we will soon be forced to flee all the same. “Spreading out [into space] may be the only thing that saves us from ourselves”, declared the late astrophysicist Stephen Hawking in May 2017 in a speech in Trondheim in Norway. And he urged us to hurry up, saying that humanity has 100 years to develop the capacity to colonise a foreign planet. Hawking was convinced that we can succeed, that the technologies we need to make such a leap are almost in our grasp, and that the notion of settling on distant planets is “no longer science fiction”. But Ben Moore, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Zurich, is sceptical. He expects that we will build a station on the moon in the next ten years, and that in the next 100 years people will land on Mars, but the notion of colonising space with millions or billions of people is something he regards as unrealistic. Mars is extremely hostile, and would first have to be made into a habitat similar to Earth. ‘Terraforming’ is the name for this notional transformation of a planet. “It sounds great”, says Moore, “but it remains utterly in the realm of science fiction”.

It is also as yet barely conceivable how we might put 7.5 billion people into space. Elon Musk, the founder of Tesla and a private space entrepreneur like Bezos, is aiming to colonise Mars by building reusable rockets with space for 100 passengers. At its cheapest, he reckons it would cost USD 140,000 per passenger. So our escape to Mars will only be available to very few people in the foreseeable future.

The new world engineers

But there are advocates of geoengineering who believe that an evacuation will not even be necessary. They want to intervene in the climate system of the Earth in order to avert the impending catastrophe. But may we truly take on the role of ‘world engineers’ and intentionally alter our climate system? “We must”, insists Ivo Wallimann-Helmer, an environmental ethicist at the University of Fribourg, and co-author of a white paper from 2017 on the opportunities and risks of geoengineering. At the UN climate conference in Paris in 2015, governments from across the world set themselves the goal of lowering global warming to less than two degrees higher than the average in pre-industrial times in order to avert the dangers of climate change. Wallimann-Helmer believes that this goal will probably only be attained with the aid of geoengineering. “Two-thirds of all scientific analyses assume that this will be necessary if we are to keep to the two-degree barrier. This is why it makes sense to think about the fair governance of these technologies”.

Two different approaches are currently being investigated by researchers. The first aims to take CO2 from the atmosphere – such as is planned by the Zurich company Climeworks. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), long-term projects to remove CO2 from the atmosphere will be essential if we are to keep to the two-degree limit. But these technologies are still experimental, and it is uncertain whether we will ever be able to build up sufficient capacity to make a substantial impact. This is why the IPCC is promoting the cultivation of quick-growing plants like maize, which can be burned to produce energy. The CO2 produced by this would be separated and stored. The components of such a procedure are technologically well developed, and several commercial plants are already in operation. In order to be able to compensate for the 12 to 16 billion tonnes of annual negative emissions calculated by the IPCC for 2050 and beyond, current estimates suggest that 300 to 800 million hectares of land would have to be reserved for energy crops. That is a surface area equivalent to one or two times the size of India, or – according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) – at least one fifth, and possibly more than half, of all agricultural land today.

Think of our descendants

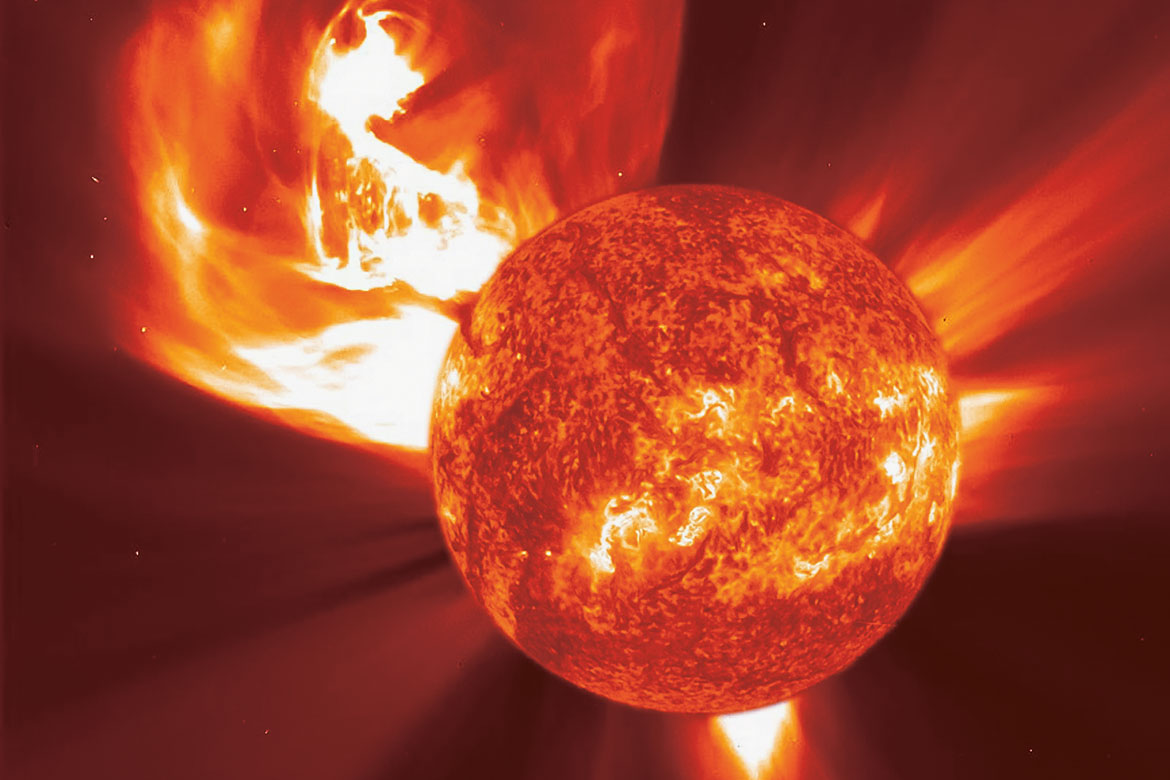

The second approach discussed by the IPCC aims at creating the technology to influence solar radiation in order to reduce global warming. It would be possible to achieve a cooling effect if one were to introduce sulphur particles into the stratosphere, for example. The impact of this would be similar to a large-scale volcanic eruption. Artificial clouds over the seas could also cool down the climate. However, manipulations of this kind could alter rainfall patterns, and trigger droughts or storms. “They have never been tested on a large scale, and come with risks that are scarcely foreseeable at present”, explains Ivo Wallimann-Helmer. Given the precautionary principle, it is wise to exercise extreme restraint”.

Geoengineering also brings a whole series of ethical conflicts and issues of justice with it, says Wallimann-Hellmer, such as in matters of land use, water use and the distribution of risks and side-effects. “If we reduce solar radiation, this will not have the same impact everywhere on Earth. So who is to be allowed to decide what? And how might one compensate those who are negatively affected? We would have to clarify global and regional questions about what is fair, and it is possible that an international set of rules would have to be drawn up”. We would also have to bear future generations in mind, adds Wallimann-Helmer. “For example, if we spray particulate matter in the atmosphere, our descendants will have to keep coping with the continuing symptoms – otherwise, there could be a rapid rise in temperature that would threaten society and the ecosystems with mighty problems”.

The burden will be even greater if we put all our chickens in the geoengineering basket, and this technology fails to develop quickly enough to be of real use. “Geoengineering could tempt us into failing to reduce emissions”, explains Wallimann-Helmer. “If we do nothing about climate change and simply hope there will be a technological solution, this would also be an ethical decision – but a very dangerous one”.