IN THE PICTURE

Bacteria in orbit

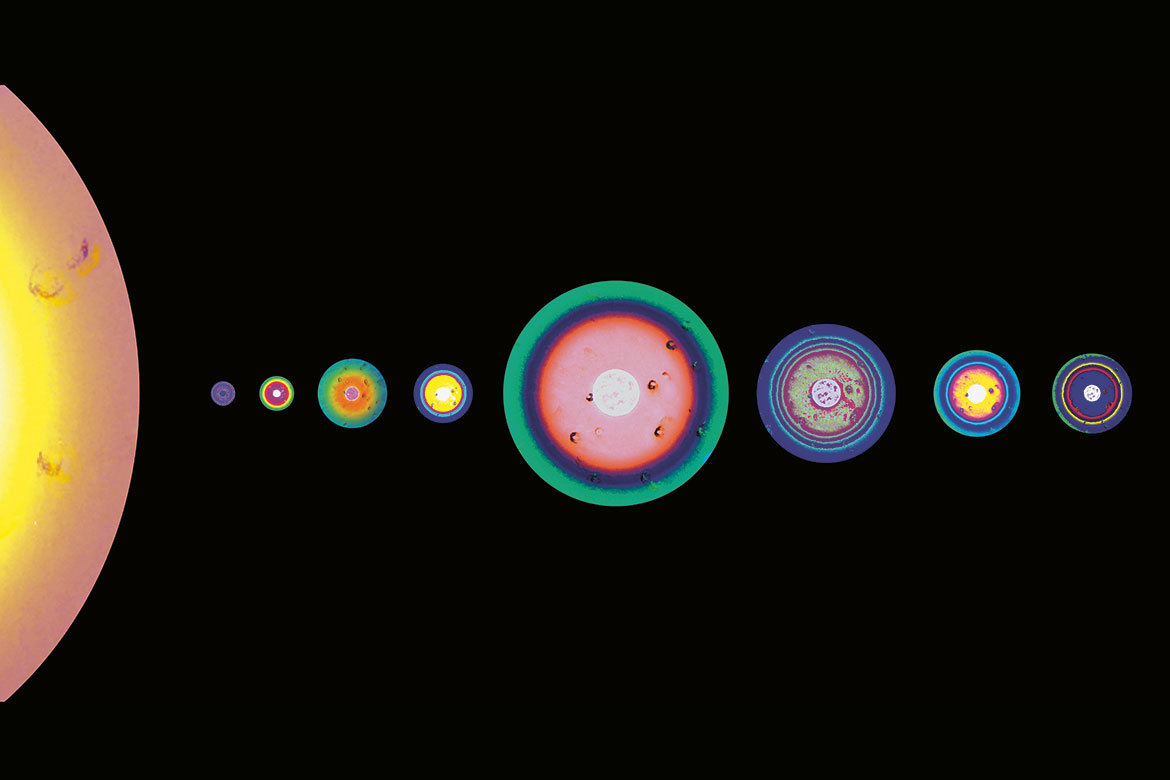

Colours and patterns indicate whether genetically modified bacteria behave as desired.

Bacteria arranged in Petri dishes more beautifully than perhaps they ever have been. | Photo: Javier Santos-Moreno

“In this image, we’re not at all on the scale of the solar system. What seems to be the Earth here, for example [the third planet from the ‘sun’ on the left, Ed.] is actually a 10-centimetre diameter Petri dish with billions of bacteria in each concentric ring.

Bacteria are the world to Javier Santos-Moreno, a postdoc in the Department of Fundamental Microbiology at the University of Lausanne. “I work with the species Escherichia coli in synthetic biology. I design and build genetic circuits in order to control them”, he says. The world is far from being monochrome. Indeed, to check whether genetic modifications will produce the expected effects, the researcher uses colours. Some bacteria function like molecular clocks and oscillate between several colours at precise intervals. Others produce different spatial patterns depending on the genetic circuits inserted.

That’s what we see in this reproduction of the solar system. In the Petri dish that represents the Earth, Santos-Moreno generated a gradient of arabinose to which the bacteria responded through their genetic circuitry. They produced different colours depending on the amount of arabinose present around them. The other planets are variations on the original, created with software. “I played with the size so that the proportion of the planets would be true to reality, and with the colours so that the result would be aesthetically pleasing”, says Santos-Moreno.

There’s a reason bacteria are being trained to follow orders and please the eye. “To make drugs or to synthesise biomaterials, for example. Bacteria are not necessarily harmful”, he says. In his laboratory, however, he is far removed from these applications. “I do basic research. It may seem abstract. That’s what motivated me to take this picture. I think a strong image can arouse curiosity”.