in brief

How countries manipulate economic data

Governments like to present their economy in the best possible light. An analysis of recent scandals reveals various strategies to improve statistics in different shades of grey.

Public protests in Argentina against tax increases and inflation. Image: JSPhoto / Alamy Stock Photo

Across the world, states compete for the highest economic growth, the lowest unemployment figures and the smallest budget deficit. Such economic indicators can determine the success or failure of governments in office, and they influence the granting of loans and a country’s economic future. In recent years, numerous studies have shown that governments manipulate macroeconomic indicators. Lukas Linsi, an assistant professor of international political economy at the University of Groningen, has now examined how governments do this.

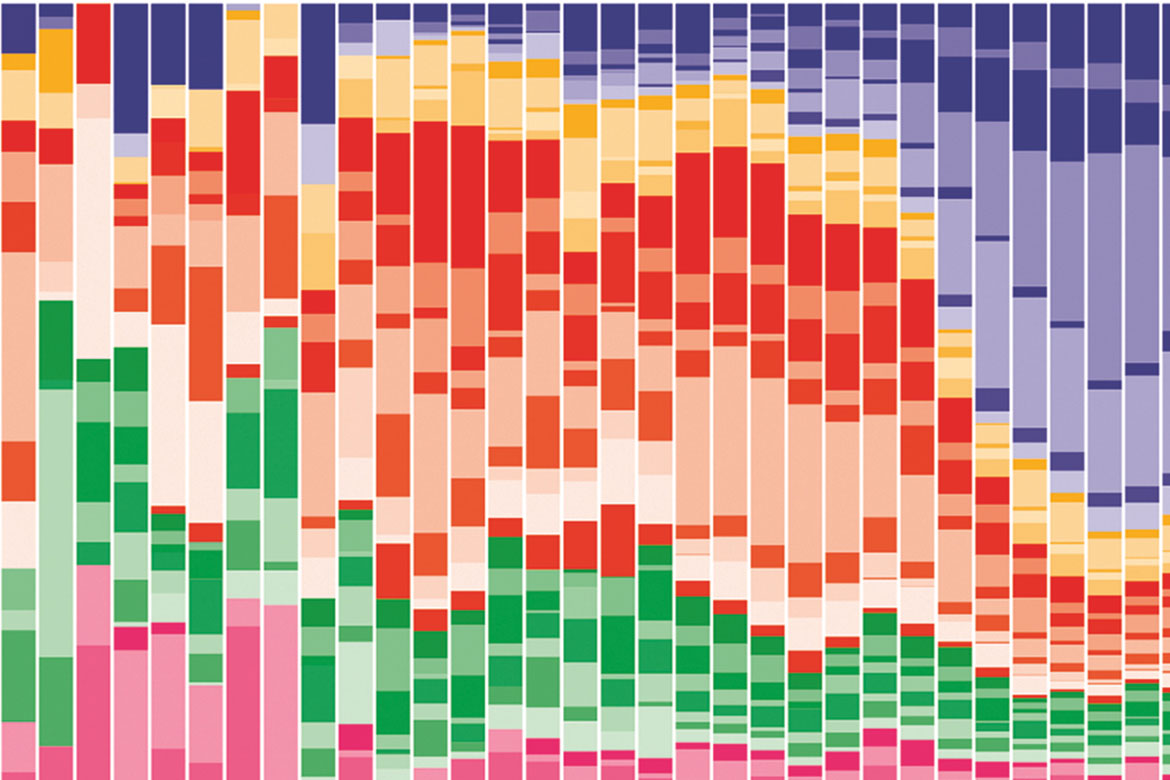

Together with Roberto Aragão from the University of Amsterdam, he analysed three prominent cases from countries that in recent years caused scandals by manipulating macroeconomic indicators: Argentina (optimising inflation statistics), Brazil (embellishing public debt) and Greece (adjusting budget deficits). For their investigation, the researchers looked through numerous documents and spoke with finance ministers and government officials from the time. On this basis, they defined four strategies that governments use to improve their indicators. These include the manipulation of raw data, the exploitation of methodological leeway, the optimisation of estimates, and the falsification of figures collected for macroeconomic indicators.

“It has been shown that the line between accurate and manipulated data is much less clear than is often presented in public discussions”, says Linsi. Often, governments do not know the exact data themselves, there is widespread discussion about the most reliable methods, and some states even fail to carry out precise surveys of their population figures. “Economic indicators are much less clear-cut than many think”. This phenomenon is not limited to the developing world. Adjusting data is also widespread in highly developed countries. These findings raise further questions, says Linsi. “Where are we to draw the line between acceptable and unacceptable data adjustments? And who should have the power to determine where it lies?”