Feature: Lessons from the pandemic

How the mask came upon us

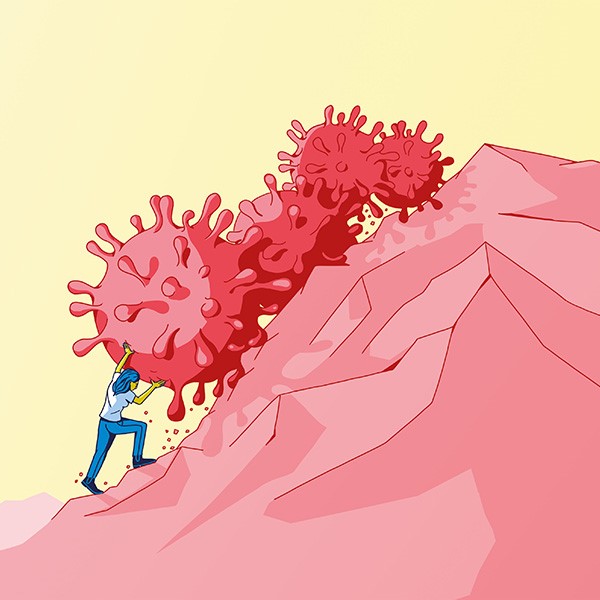

Science provides facts, and politicians base their decisions on them. However seductive this ideal situation might sound, the reality is actually much more chaotic. We take a closer look at how compulsory facemasks became the norm.

Some people go for elegant masks. But it remains unclear whether they truly protect you from SARS-Cov-2 in your everyday life. | Image: Vera Davidova/Unsplash

The relief on the part of many scientists and journalists was palpable on 6 July when the Swiss Federal Council ordered the compulsory wearing of face masks on public transport. Better late than never was the general mood in the press. But in fact, it was still unclear whether or not protective masks actually prevent coronavirus infections.

Masks naturally filter out particles and droplets from the air. The question is whether this can suffice to reduce the infection rate. Up to now, comparisons between those who wear masks and those who don’t have been pretty consistent: people who wear masks are less likely to get infected. But such observational studies have a problem: people who voluntarily began wearing masks in their everyday lives before they were compulsory are not directly comparable with the rest of the population. They are more likely to be cautious in general, and probably live in a more exclusive, more secure environment than most. And even when we compare groups in different countries, there are still many disruptive factors. South Korea and Switzerland are fundamentally different, for example, not just in their attitude to wearing protective masks.

In order to exclude alternative explanations for the lower infection rates among mask-wearers, we have to be able to assign people randomly to the different groups. But such randomised, controlled studies are difficult to carry out – especially outside of a hospital environment. But this is precisely the crux of the matter with the novel coronavirus: Will normal citizens possessed of average personal discipline be less likely to become infected in their everyday lives if they wear a mask? The few extant studies are all focused on influenza – such as family members of children infected with the flu who have been instructed to wear masks. A systematic review of high-quality studies, made by researchers in Hong Kong, reported on 6 February 2020 that wearing masks only had a small, statistically insignificant impact. So there must be something that annuls the useful filter function of masks in everyday situations. Perhaps people cease social distancing when wearing masks, or perhaps they touch their faces more often.

This opinion corresponded to the state of knowledge on the part of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the FOPH at the start of the pandemic. Apart from the dubious efficacy of masks in everyday life, the decision-makers also had to take into consideration their availability, the costs, and the attitudes and competences of the people involved.

More studies were published, but none of them were randomised and controlled, and few of them dealt with the novel coronavirus. Nevertheless, the mood among scientists changed over the course of the pandemic. After all, there were hardly any studies that could prove that masks actually caused any harm – such as leading people to abandon social distancing. So it seemed better to wear a mask for good measure, even when it might have no impact whatsoever. This precautionary approach began to acquire support, such as an analysis carried out by British researchers that was published on 13 May 2020.

But even before this analysis, the FOPH had begun recommending masks on posters they were issuing to warn against infection. This was at a point when enough masks were finally available. Meanwhile, the WHO itself commissioned a review of wearing masks that was exclusively aimed at coronaviruses. It was published on 1 June 2020. But up to this point, only observational studies were available for evaluation: 26 in total, of which only three dealt with everyday situations, and these dated from the SARS epidemic of 2002, which did not spread very far. Two randomised, controlled studies on Covid-19 were underway in early June, but not yet complete. The authors nevertheless argued in favour of everyone wearing masks, and the WHO changed its stance accordingly. The Swiss Covid-19 Science Task Force also referred to the WHO’s decision in its own recommendations.

But in mid-June, the number of reported infections began to rise again. Scientists began to exert pressure with emotive Tweets, and journalists joined in. The hashtag #TeamMask began to make the rounds. The Federal Council reacted by introducing compulsory masks in public transport as of 6 July, despite the fact that the scientific evidence about their efficacy against coronaviruses in everyday life has barely changed.