Genealogical research

Jewish by DNA

“Discover your history!” This is how one company advertises its DNA analyses, which promise to tell people where they’re from. We look at the data that lie behind these services, and at the stories that DNA analysis can really tell us.

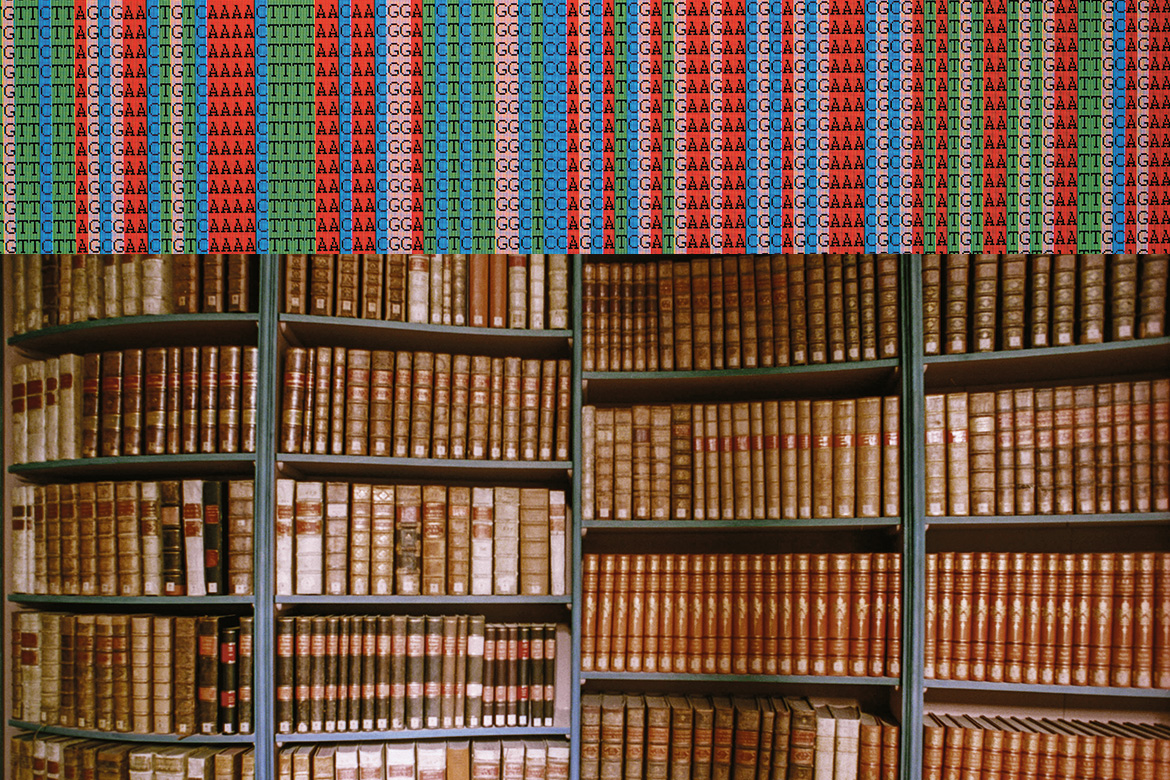

Whether through gene sequencing or archival research: if you want to know more about your origins, you need expert help. | Images: Alan Philipps/Getty Images; Sigi Tischler/Keystone

A woman sends a DNA sample to a commercial company for analysis. She would like to know what region her family originally comes from. The service costs just under CHF 200. The result of this ‘ethnicity estimation” is as follows: 46 percent northern, western European. That’s no surprise, because her mother’s family has lived in Central Switzerland for centuries. Then there’s 23 percent southern Italy or Greece. That’s no surprise either, because her father came to Switzerland from Palermo as a young man. But then comes something unexpected: 13 percent Ashkenazy Jew (i.e., European Jew). The woman who commissioned the analysis does a quick calculation and realises that one of her great-grandparents must have been Jewish. But she knows nothing of this. She imagines that her great-grandmother (she prefers to think it must have been a woman) might well have lived through the fascist era in Italy. What might have been her fate?

When faced with a story like this, there are actually more fundamental questions one should ask. Just how does the company in question come to this result in the first place? And what does it even mean to be part-Jewish? Do such analyses perhaps even foster racism? And lastly, how can the woman find out just who her great-grandmother really was?

DNA from ancient graves

Marianne Sommer is a professor of cultural sciences at the University of Lucerne. She has published a book about identity and the history of gene sequencing, and has been looking into the services offered by companies such as Familytreedna, Igenea and Ancestry: “These DNA tests are supposed to provide information about the so-called haplogroup (the Stone Age), about ancient tribes (900 BC to 900 AD), and about the more precise country of origin of someone’s family (1000 AD to 1300 AD). The haplogroup test is offered by most service providers in the field. If we imagine the human family tree as beginning with our molecular ancestors, then the haplogroups are the branches of the tree”.

Not all of these companies offer details on the ancient tribes. This test is based on studies in which DNA samples of living people are analysed and compared with those of people who have lived in specific regions for many generations. Today, we can even combine these with studies of DNA from graves from the eras in question. Roman Scholz is a genealogist who works for Igenea, and he explains their approach as follows: “We chose to focus on the ancient tribes, because we can differentiate clearly between them, which isn’t so easy with more modern peoples”.

But let us return to the Jewish community. Their members have lived in the diaspora for millennia. It would thus seem natural to assume that their genome has become more and more intermixed with the population of the regions in which they have lived. However, this supposition was already proven to be untrue by the Italian geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza back in the 1970s, as Marianne Sommer has explained in her work on population genetics and the great diasporas. Cavalli-Sforza compared the genome of contemporary Jews (men and women) across the whole world with members of the Jewish community who still live in the Near East. He was ultimately able to prove that “the diaspora groups were genetically closer to the population in their region of geographical origin than to the population of their host country”. His investigations also proved that the DNA of a contemporary population in a specific region can be used to approximate the DNA of their ancestors in the same region.

We all mix together – or not?

Marianne Sommer points out certain market-specific aspects of the modern DNA-analysis providers: “Although their manner of determining genealogy functions similarly in each case, the different companies tailor their products to their own particular target groups”. If a genealogy company offers to trace back one’s DNA to ‘ancient tribes’, “this means that someone can be identified as a ‘Teuton’, and their region of origin since the Middle Ages will be ‘Germany’, even though no such country existed at the time. This is potentially controversial because it can make some people feel they are more German than others”. Other providers specialise in African-American DNA. And as the American anthropologist Nadia Abu El-Haj has shown, Familytreedna has a high percentage of Jewish clients.

At the same time, the whole issue is something of a game that is typical of our age, according to Sommer. If someone can trace their lineage back to the Phoenicians, they might take this as the reason they like to travel so much. The method for assigning someone’s genome to different geographical regions also promotes an understanding of how our own identity is something mixed. The analysis is made possible by programs such as ‘Structure’, which for the past two decades has been assigning individual genome samples to different groups based on similarities between them. It makes no difference to the program whether or not people are already considered to belong to any specific ethnic group.

Authoritative genes

Sommer nevertheless has reservations: “All these offers tend to reduce your identity to your DNA. It is ‘biologised’. But being Jewish isn’t just a matter of your gene sequence. Sure, your ancestry is part of it, but how you live your faith, and your sense of belonging to a community, are far more important. Nevertheless, genetics are a branch of science that has assumed an incredible degree of authority over us in our everyday lives. Genes are seen as a fundamental aspect of who we are”.

Besides assigning us to different ethnicities, many companies also offer to create automated family trees that are in fact a very different branch of genealogy. These were conventionally the field of genealogists, professionals and amateurs alike; in Switzerland, they come together in the Swiss Society for Genealogical Studies (SSGS). They visit village and town archives, and track down their forefathers in the church registers. “When you are provided with a family tree by one of these online companies, it can trigger expectations that simply cannot be fulfilled”, says Kurt Münger, the president of SSGS. Jürgen Rauber is a professional genealogist, and he warns that “you have to treat the information offered by online companies with the greatest of caution. It has to be verified and confirmed by reference to primary sources”. But both Rauber and Münger see the positive side of what’s on offer. “What’s good is that Myheritage, for example, has a very big database that means you can find information about your forefathers pretty quickly”, says Rauber. Münger agrees: “We are actually grateful that we can now also use computers to carry out genealogical research”.

Either way: the woman who would like to know the fate of her putative Jewish great-grandmother will need the help of experienced researchers such as Rauber. Because an automated analysis of her genome will provide her with next to no information to help her.