in brief

Can less light prevent premature births?

Mice give birth later when they live in the dark. Researchers had expected the opposite.

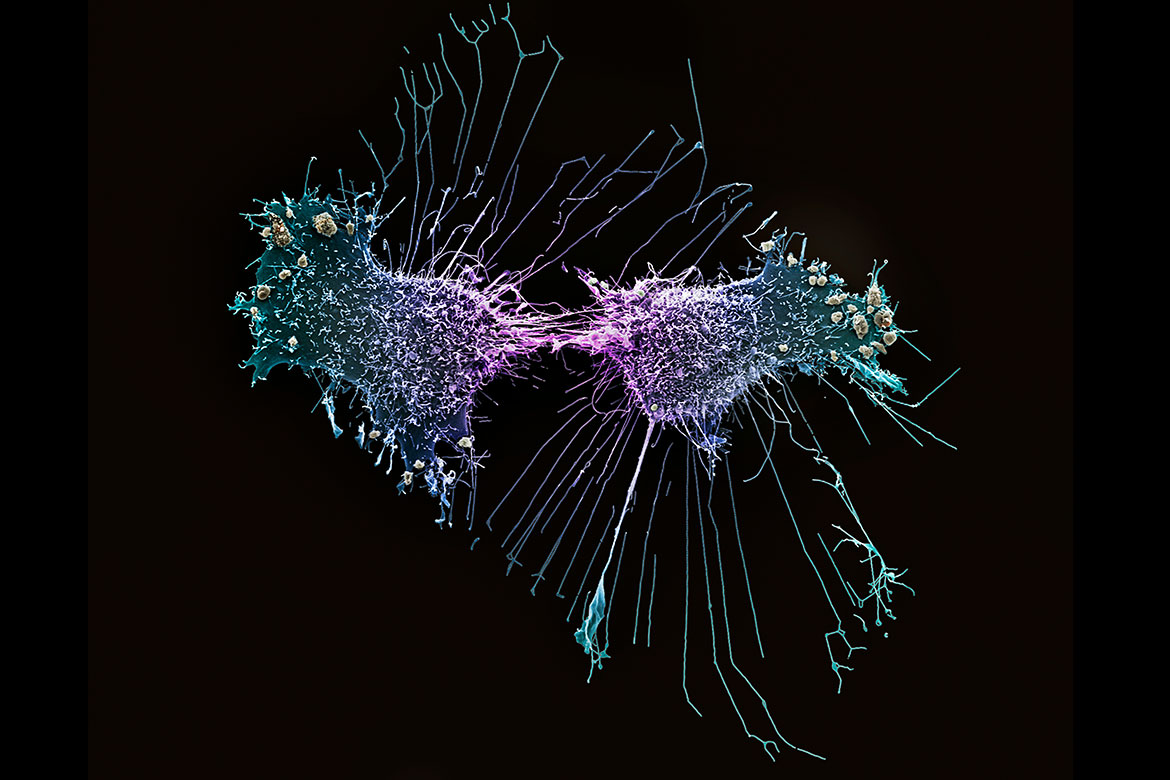

Mice are born later when their mothers spend more time in darkness. | Image: zVg

In some species, such as humans, births tend to occur at night. In others, it’s daytime. A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms could not only improve livestock husbandry but also prevent babies from being born too early. A laboratory at the University of Fribourg has discovered that light deprivation at the end of gestation delays the birth of mice, without their internal clocks seeming to be involved.

In their study, scientists compared wild type mice exposed to light every 12 hours throughout their entire gestation, with some, at the end of gestation, being permanently illuminated and others plunged into complete darkness. Normally, the internal clock of these rodents follows a cycle of almost 24 hours, but it wavers from this precise rate if they are exposed to light every 12 hours. Scientists therefore expected mice deprived of light to give birth earlier than those subjected to alternating day and night, but the opposite came to pass. In the dark, individuals from a lineage without a working internal clock gave birth even later.

The question remains as to the transferability of these results to livestock and humans. “They’re mammals like mice, but they’re diurnal. We should first check whether light deprivation has the same effect on births”, says Tomoko Amano, the study’s first author, who is currently a professor at the University of Rakuno Gakuen in Japan. “If this is the case, darkness could be tested in animals to prevent premature births. But probably not in pregnant women because lack of light can have health consequences”, she concludes. On the other hand, it could encourage them to turn off the light earlier in the evening - a measure without adverse effects.