Feature: A smart future for food

From the field to our plates

Almost a third of Switzerland’s environmental impact is caused by the production of foodstuffs. We offer five graphs to show how food might be made smart and sustainable.

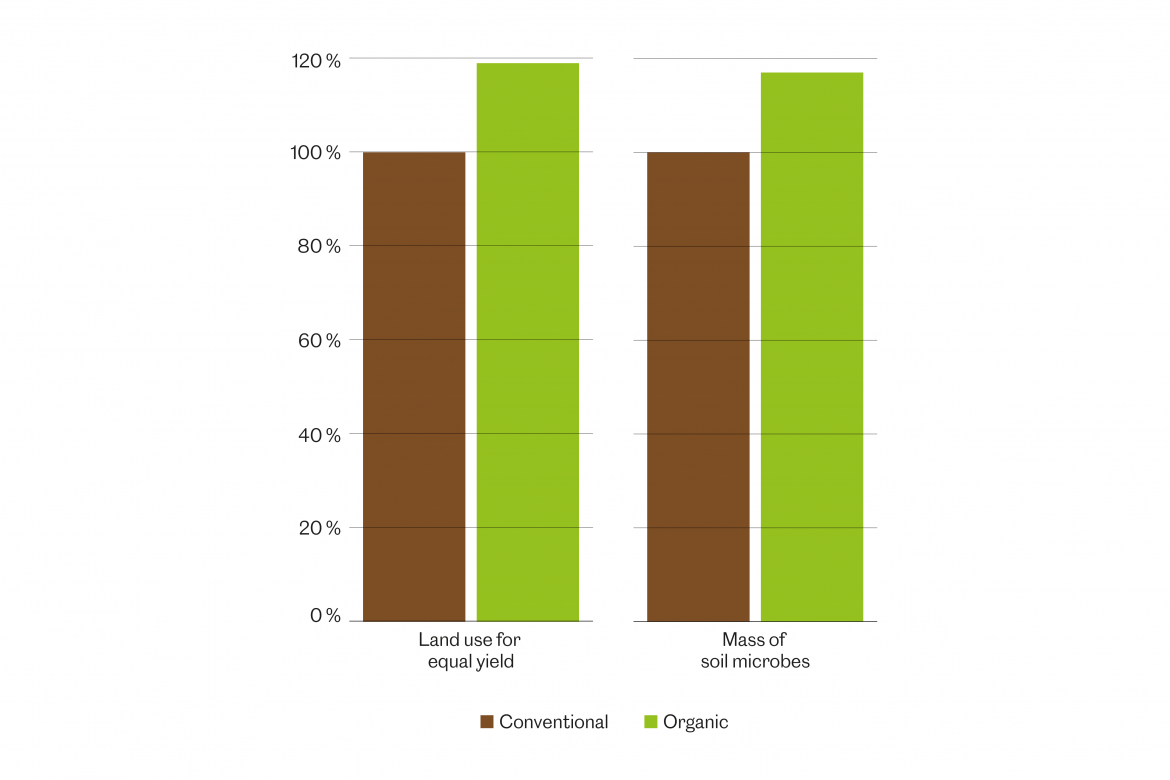

Cropland: limiting it to keep it fertile

Is conventional or organic crop cultivation better? Before we can answer this question, we first have to clarify a lot of other things. Are there animals on the farm, or are only mineral fertilisers used? What crop rotation is practised? How are pests controlled? A long-term study by the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) has for several decades been comparing different, typical forms of Swiss agriculture. The results are clear: organic farming is in almost all cases better for the environment. Our graph shows the mass of microorganisms in the soil, which are a sign of biodiversity and fertility. But there’s a big catch: organic farming needs more land to produce the same amount of foodstuffs.

A research group at FiBL has proposed two new forms of cultivation management for the German agricultural sector: the model ‘Öko 4.0’, – an organic model in which breeding methods using molecular biology and synthetic substances would be allowed for purposes of increasing yields; and the model ‘IP+’, which would allow conventional farming, albeit with stricter regulations for fertilisers and crop rotation, so as to improve the protection of the soil. There are many more ideas, too. What matters is: we have to be creative.

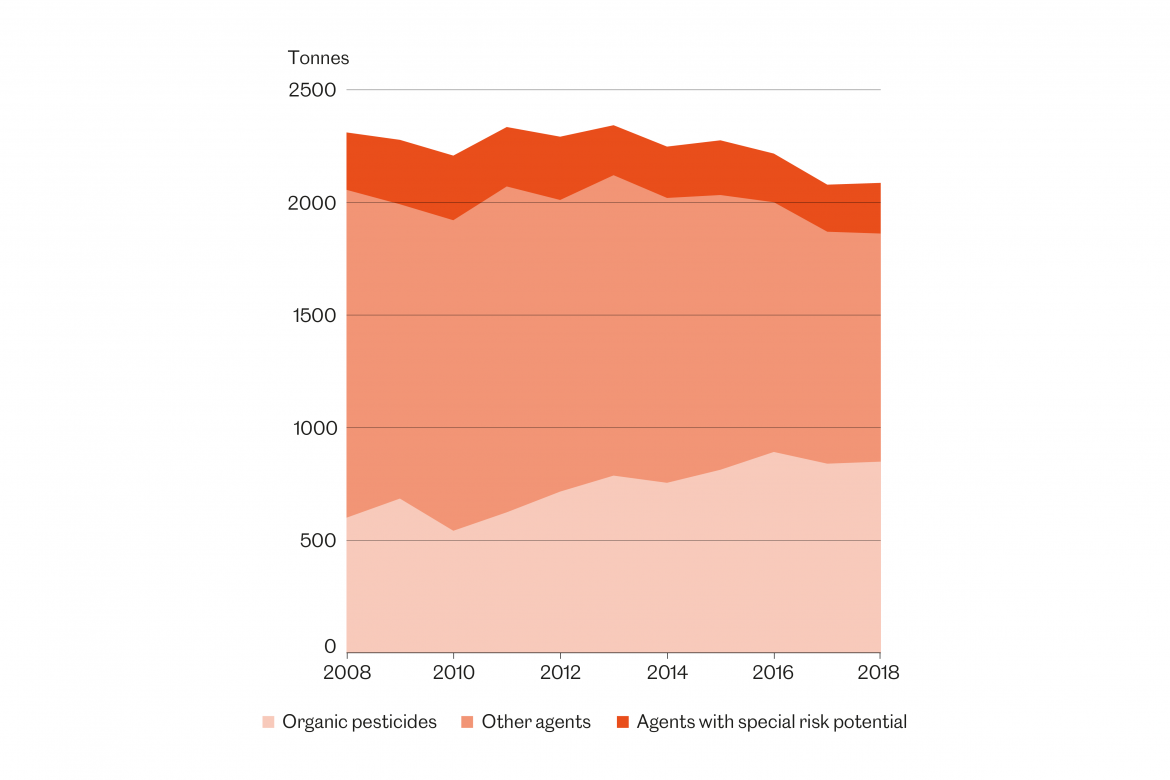

Using pesticides that are less harmful and more degradable

Pesticides are a threat to our drinking water. But agriculture without pest control can’t exist, not even on organic farms. Sales of substances permitted in organic farming – such as sulphur and paraffin oil – have increased in recent years. This is both because the number of organic farms is increasing, and also because conventional agriculture is increasingly relying on such agents too. As a result, the past few years have seen a concurrent fall in sales of the less conventional substances such as the infamous glyphosate.

Substances with special risk potential are still being sold, even though the curve is pointing slightly downwards. They are in some cases even allowed in organic farming – such as the heavy metal copper, which is used as a fungicide, but which accumulates in the ground. The bottom line is that these especially dangerous substances should be replaced, and other forms of pest control employed wherever possible.

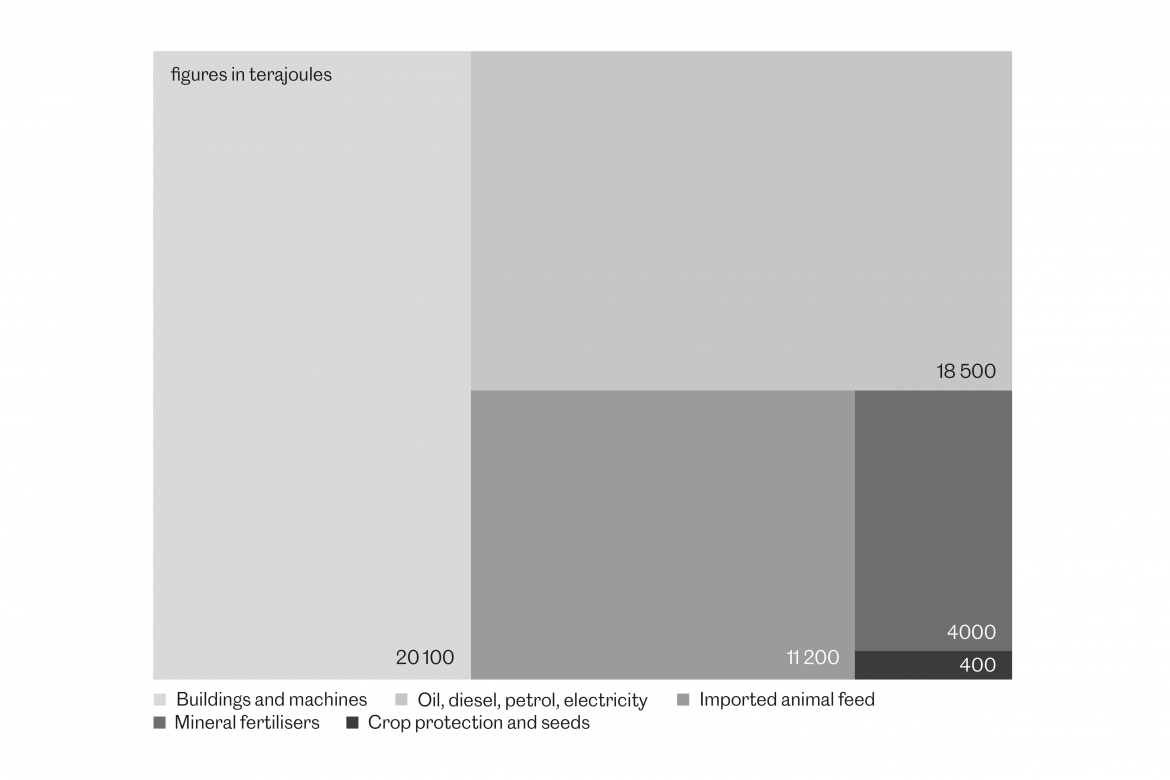

Energy consumption: cutting imports of animal feed

Agriculture transforms sunlight into foodstuffs. But to do this, it also needs external energy. Barns have to be built and heated, tractors manufactured and run, oil has to be fetched from the ground, and electricity generated. Ultimately, almost everything depends on fossil fuels that emit pollutants and greenhouse gases. The efficiency of Swiss agriculture in terms of external energy needed to produce one unit of nutritional energy has been sinking. In the year 2000, the cost of each nutritional unit produced was 2.0 units of energy; by 2017, it had risen to 2.3 units.

Two big energy guzzlers are imported animal feed and the production of mineral fertiliser. The consumption of fertiliser has almost halved in the past two decades, but in the same time period, the amount of animal feed imported has almost quadrupled. Swiss grasslands alone are not capable of providing enough feed for our meat production. This means that if we are to become sustainable, agriculture will have to lower its imports of animal feed, and switch to renewable energy.

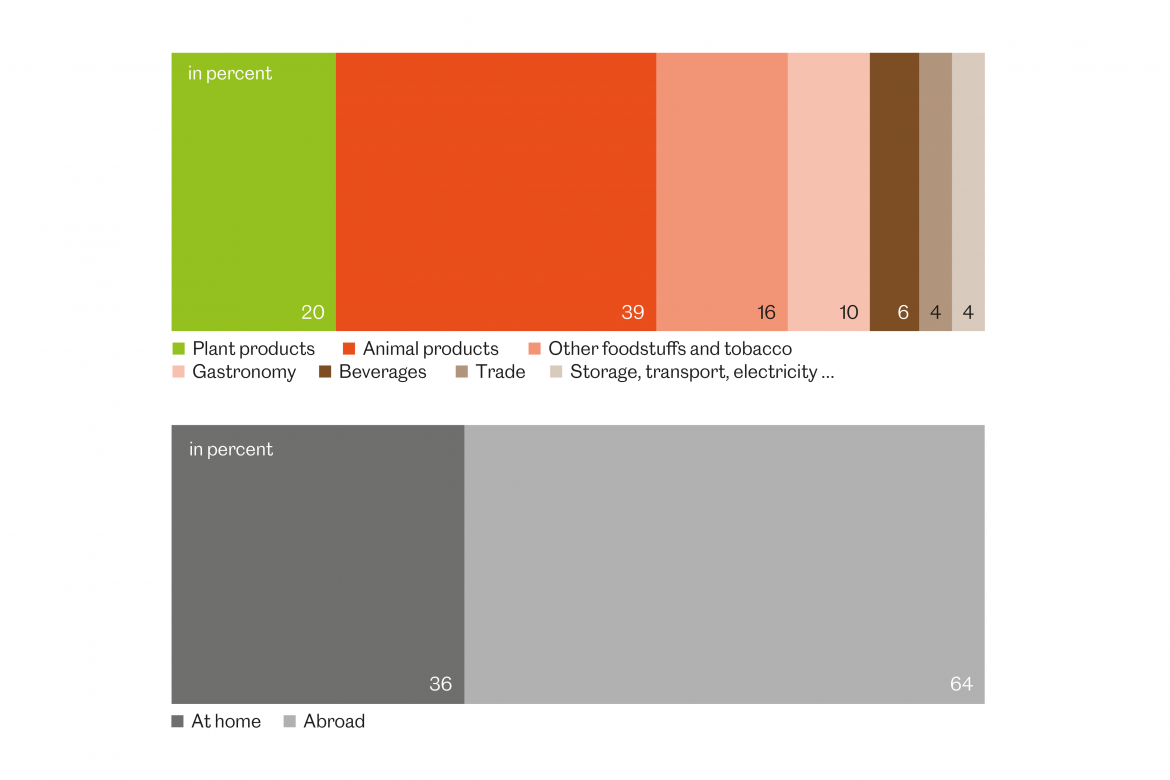

Reducing animal products on the menu

It is difficult to determine the precise burden to the environment that is caused by the consumption of animal products such as meat and dairy products in Switzerland. To do this, researchers from the National Research Programme ‘Healthy Nutrition and Sustainable Food Production’ (NFP 69) have used an environmental/economic model to calculate the impact of the value chains of the food industry and to depict them in assorted statistics. Problems such as land use, water consumption, the emission of pollutants and greenhouse gases are here converted into the recognised units of environmental impact points.

The more points by which a factor exceeds the politically defined objectives in this model, the more weight it is given. When calculated like this, animal products cause at least 40 percent of the overall environmental burden. Other foodstuffs also contain animal products (either more or less obviously), even ready meals like tortellini. In gastronomy, the proportion of meat consumed is also considerable. Overall, the biggest environmental impact in food production occurs abroad, however. If we want to be more sustainable, we should eat more Swiss products, and refrain from consuming animal products as much as possible.

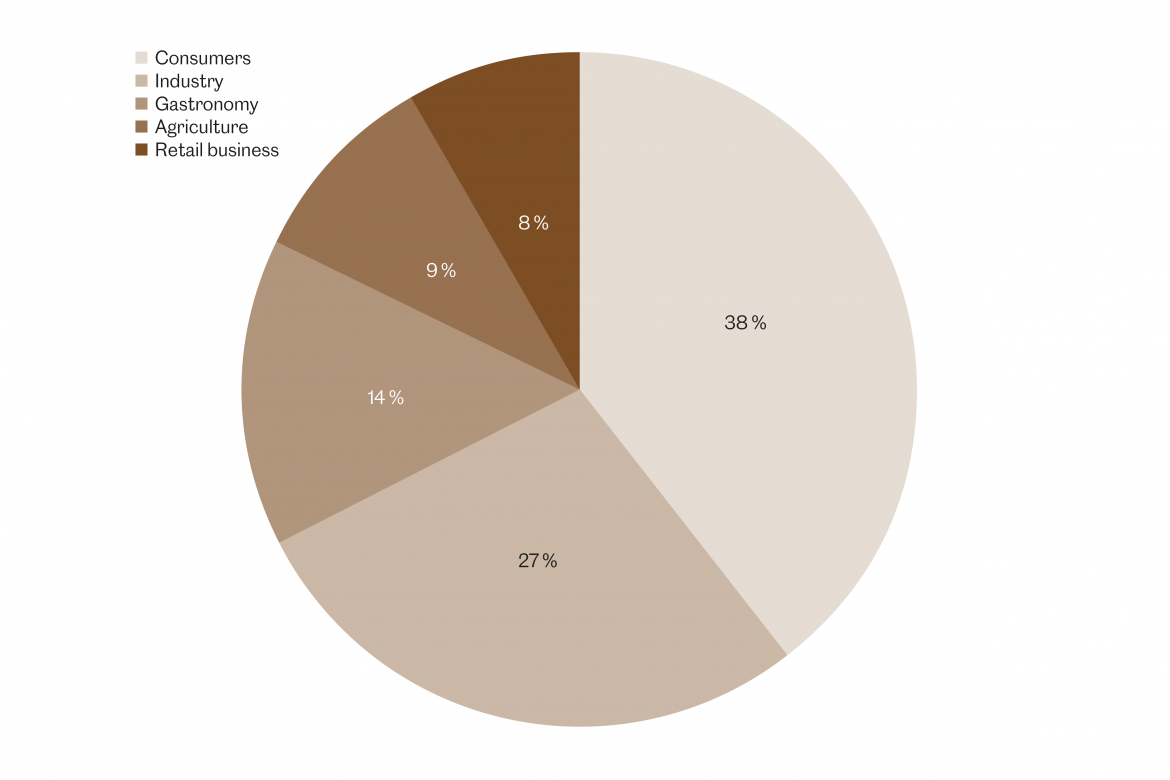

Waste: achieving a better use of end products

Roughly a third of all foodstuffs are not consumed. That means almost 190 kilos of food per person are thrown away in Switzerland every year. This makes up a quarter of the environmental impact caused by the food industry.

Consumers throw away the most– almost 40 percent of total food waste. Whatever goes bad in the fridge or remains uneaten on our plates increases our environmental footprint. The food industry wastes almost as much, but surprisingly, food waste in the retail business is less drastic. Switzerland has now committed itself to reducing food waste by half by the year 2030.