OPEN SCIENCE

Open data seeks citizens (m/f) for serious relationship

Open science promises to democratise access to its discoveries by making them available to the general public. But this potential remains under-exploited.

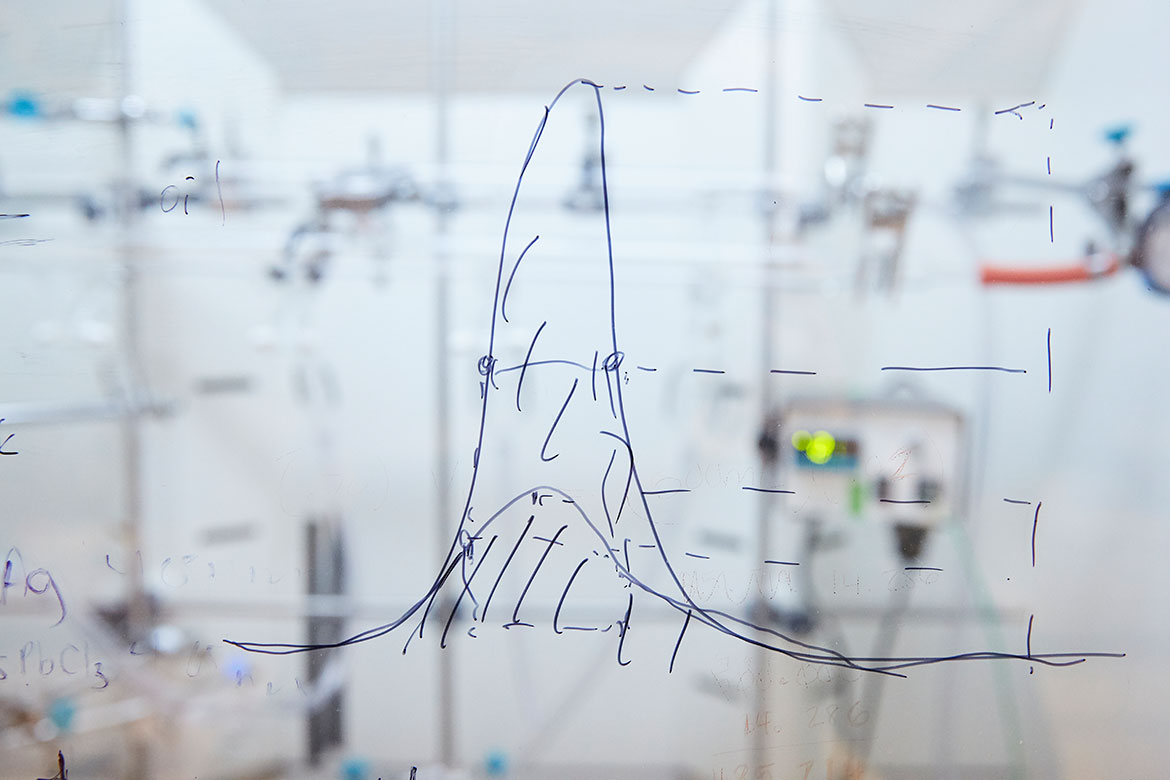

Lab windows are often used to make notes. But transparency in science doesn’t mean that laypeople will necessarily be able to comprehend their results. | Image: BM Photos/SNSF

The corona-data.ch website with its three million monthly views is a good example of the power of open data. Its clear and relevant visualisations of the Covid-19 epidemic, made by a doctoral student in chemistry in his free time, are an example of what open science could bring. By facilitating the free flow of data, this movement aims to accelerate discoveries, encourage interdisciplinarity, improve the practice of research, and open science to society. The results of publicly funded research “belong to the community”, the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) points out.

Open research data invites actors outside the academic world to re-appropriate the data resulting from research work. “It offers scientists and citizen-researchers greater opportunities to advance science”, according to the UK’s Royal Society. In Switzerland, open science is gradually taking shape. Since 2017 all projects submitted to the SNSF must include a data management plan for future publication.

But is this open access data of interest to the general public? Very rarely, as the research suggests that we conducted for this article.

Two cards and one reference

One example is EnviDat, a platform launched in 2016 by the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL). It currently references more than 300 datasets that map Switzerland’s forests, record dead wood, document the victims of natural disasters or predict the effects of climate change on mountains. Despite the obvious interest of these topics, this resource seems to remain largely ignored by non-specialists, judging from the examples offered by Gian-Kasper Plattner, the geographer overseeing the platform.

A dataset available on EnviDat enabled Oleg Lavrovsky, a computer scientist active in the open-data scene, to create a map of avalanche victims over the last 25 years. “I have no direct connection to environmental science”, he says. “It’s a project I did for myself over a weekend”. The visualisation was published on the opendata.ch specialist forum, but seems to have been of no interest to the media, ski resorts or mountain guides.

Two further examples illustrate the modest use of the broad EnviDat data. On the geographical information platform of the canton of Aargau, one can find an unmodified national map of the potential of biomass resources, which is already available on the federal geoportal, while in a directory of the Wildnispark Zürich there is a simple reference to a tree inventory.

Of course, it is possible that other WSL data have been taken up elsewhere. “Accurately tracking the use of our platform is not a priority. And you can’t easily trace projects that don’t correctly cite their sources”, says Plattner. The fact that this data does not inspire the general public does not worry him. “In my opinion, the aim of EnviDat is above all to enable specialists working in research and administration to benefit from it, even when they come from other disciplines”.

More than 22,000 patents

A different example can be found in the life sciences. More than 22,000 patents mention UniProt, an encyclopaedia of 180 million proteins managed by the Swiss Institute for Bioinformatics (SIB) and two major partner institutions in England and the USA. “UniProt is not just about hosting data”, says SIB’s Alan Bridge. “Our team does a great deal of curation and annotation work, including the use of algorithms, to make the information available and easily usable”.

Admittedly, we are still far from the vision of open science in which the data published by each laboratory is directly reused by others. And this science is not really popular, as UniProt users remain biotechnology specialists working in public research, companies and start-ups.

Telling stories

At the other end of the chain, the media don’t really allow citizens to take ownership of scientific data, except for the many graphs relayed this spring on the progress of the coronavirus. In 2019 an article on srf.ch included a questionnaire on the impact of climate change on Swiss localities. The team used scenarios published by the National Centre for Climate Services, a network coordinated by the Confederation and involving ETH Zurich, WSL and the University of Bern. “We consolidated the data, but our efforts were mainly focused on editing”, says Julian Schmidli, a data journalist at SRF. “Our job is to tell a story based on this data in order to offer unpretentious reading for the layperson”.

The media very rarely work with raw research data, says Mathias Born, a data journalist at Tamedia. “Scientists usually approach us when they have already analysed and visualised their results. This means we don’t have to reinterpret them. On the other hand, we sometimes explore data published by public administrative bodies such as MeteoSwiss”.

For Schmidli, the problem is not the complexity of the scientific data – his team has the necessary skills to analyse it – but rather inspiration and the amount of time available. “There are certainly many interesting sources, but I think that we are not yet looking for them actively enough”. The two journalists sometimes report having collaborated with scientists on issues raised by the editorial staff – such as the #MediaToo series, which documented cases of sexual harassment involving journalists. Again, this is an interesting collaboration between scientists and people outside the academic world, but one that would also be possible independently of open data.

“Populist Utopia”

These examples show that open science data are currently not very popular with the general public. The vision of a science made by the people still seems to be a dream. “Institutions such as the European Union willingly promote the idea of open, citizen-oriented and participatory science”, says Luc Henry, a former advisor for open science at EPFL. “But in this context, open-research data can be seen as a populist utopia, proposed above all to get budgets approved. Scientific research data remains extremely specialised and the general public generally does not have the tools to use it”.

The danger, says Henry, is that the democratic argument may backfire on open science. “The primary interest of open data is to improve scientific practice by promoting transparency, reproducibility and peer review of results. Many scientists are reluctant to do this for fear of being criticised or having an idea stolen from them. They then justify their resistance with the argument – not necessarily erroneous, by the way – that the general public does not care about their data”.