Research methodologies

Reconciling the irreconcilable

Mixed methods – a combination of qualitative and quantitative methodologies – are popular in the social sciences. We take a look at how they can integrate approaches that might otherwise appear incompatible, and why funding bodies love them.

The Marienthal Study of 1933 investigated the impact of long-term unemployment on a workers’ housing estate near Vienna and is regarded today as a milestone in social research.

A dispute has been ongoing in the social sciences for decades now, and it continues to this day. It’s about which research methods are better: qualitative or quantitative. Put simply, qualitative researchers ask ‘why’ and want to understand human behaviour and social connections in detail. For example, if someone wants to have children, a qualitative researcher will wonder why that’s the case. By contrast, the adherents of quantitative methods deal with quantifiable units in order to find out the extent to which a phenomenon is disseminated. For example, they might be interested in what percentage of the population desires to have children.

Both approaches have strengths and weaknesses. Critics of quantitative research claim that its standardised data-gathering methods are too inflexible and fail to take individual differences and explanatory models into consideration. And the qualitative approach is often criticised as being insufficiently representative, too subjective, or even unscientific.

Mixed methods promise better chances of success

One way of attempting to bridge the gap between them is to combine qualitative and quantitative methods in one and the same research project. “Applying mixed methods has become more and more frequent in recent years”, says Max Bergman, a professor of social research and methodologies at the University of Basel. This is not least because of how research monies are handed out. “From a research policy standpoint, mixed methods are trying to reconcile the two camps”, explains Bergman, who is also a member of the Research Council of the Swiss National Science Foundation. Often, referees for project applications like to see qualitative approaches complemented by quantitative methods, and vice versa. That has also been the experience of Stefan Huber, the head of the Institute for Empirical Research into Religion at the University of Bern. “Applications that integrate both methods have a better chance of getting accepted”, he says.

How much young men and women work

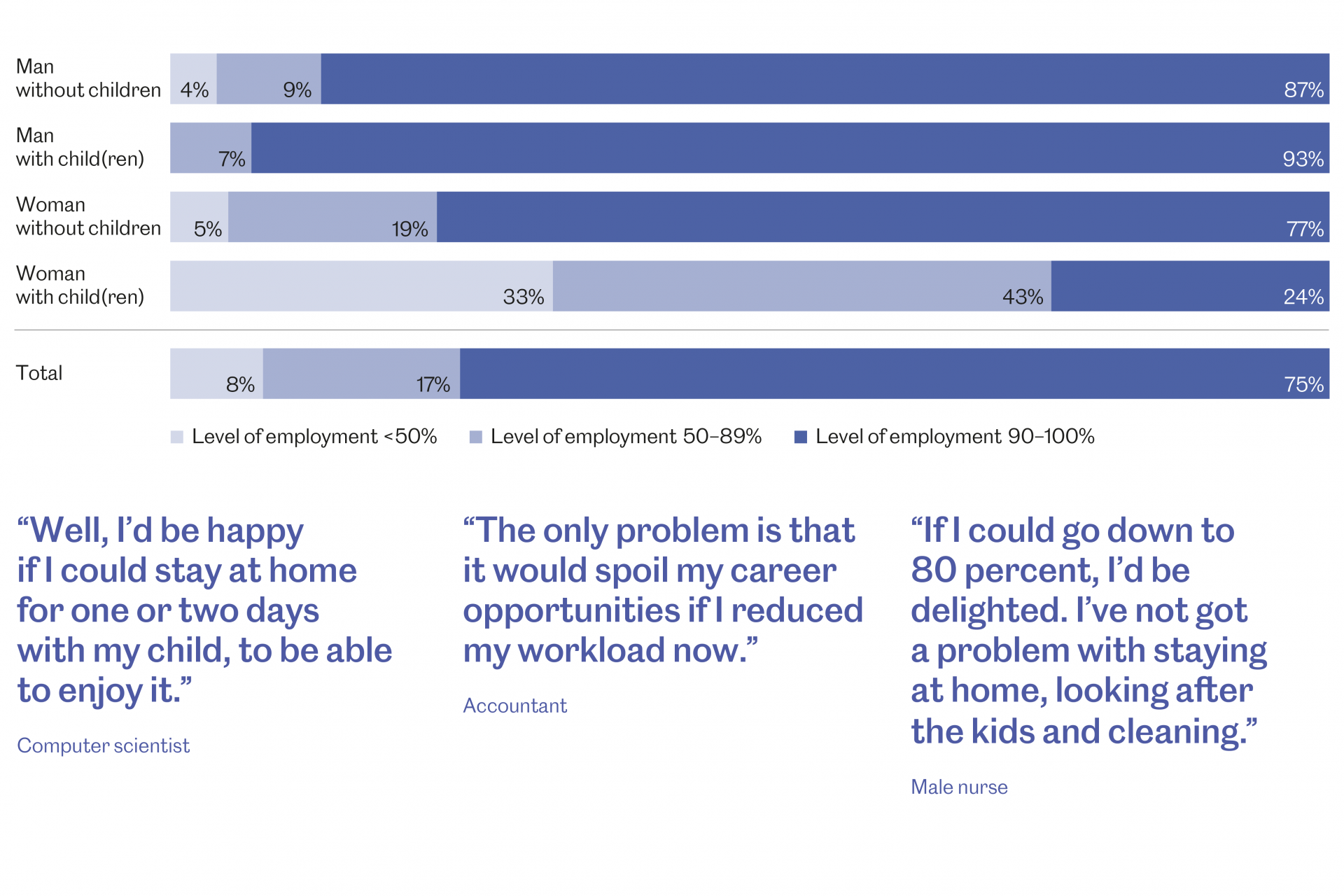

Some 6,000 young adults in Switzerland were monitored as they moved into the world of work and adulthood. A sample was made of school students completing their compulsory education, and they were then surveyed at regular intervals. The below graphic shows an evaluation of nine surveys carried out between 2001 and 2014 on the workload of young men and women. Representative groups were often chosen from the participants for purposes of qualitative research projects. The quotations are taken from 48 problem-centred interviews about what 30-year-old men think about the connections between career and family.

Infographic Bodara GmbH; Sources: TREE Study, Diana Baumgarten et al.: “If I’m going to be a father, then I want to work part-time”. Gender 2016

But financial reasons alone are not the reason for the popularity of mixed methods. There are also research reasons for it. “Mixed methods can provide more meaningful research results and a more accurate depiction of the complexity of systems”, says Bergman, who has published numerous articles and books on the topic. Findings from individual observations or interviews can serve to develop a hypothesis that can then be evaluated by means of a statistical survey. Conversely, quantitative research results can be consolidated if you select individual test subjects from a large-scale longitudinal analysis and interview them in detail.

Only connect

One example is Stefan Huber’s research project on “non-religious” people in Switzerland. In order to find out more about this group, he used data from the so-called ‘religion monitor’ of the Bertelsmann Foundation in Germany, which carried out three large-scale questionnaire surveys in 2007, 2013 and 2017, in which Switzerland also took part. They proved that the number of ‘non-religious’ people was rising. Huber and his team then picked several of the individuals involved, and carried out in-depth interviews with them. “Even if they said they don’t believe in God or go to Church, some of them still have a kind of spirituality”, says Huber. For example, they say that they meditate and sometimes feel at one with everything. “A purely quantitative investigation would have failed to notice this more differentiated perspective”.

In order to offer added value, however, it is important that projects should be conceived from the start in a manner that enables qualitative and quantitative methods to interlock and refer back to each other. And this is exactly where the main problem lies, as Bergman confirms. “Often, studies are described as being ‘mixed’ in their methods, but that is simply not the case”. Sometimes, qualitative and quantitative researchers work together in the same project, but they all pursue their own approach without their results being linked together at all.

Being taught to mix

The specialities of the researchers who are involved are actually a hurdle to collaboration. “A good mixed-method study needs both sides to have knowledge of the other’s methodologies”, says Bergman. But many researchers in the social sciences have only mastered either qualitative or quantitative methods. This is also confirmed by Véronique Mottier, a professor of sociology at the University of Lausanne. In order to teach future researchers in both fields, the University of Lausanne embarked on a comprehensive reform of its tuition in 2013. All the students of the social and political sciences have had to take compulsory elements in quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods as part of their foundation course.

Mottier insists that neither of the two methods is better than the other. “Which one you apply will ultimately depend on what research question you want to answer”. It might make more sense to carry out a purely qualitative study than to take a mixed-method approach. For example, if you want to find out the subjective experiences of individuals during the Coronavirus lockdown, a mix of methods would be more appropriate if you also want to find out how people’s social class or gender has influenced their subjective experiences.

Division is artificial

Even though mixed methods are popular at the moment, they are hardly a new trend. Researchers in the social sciences in the early 20th century used to combine qualitative and quantitative approaches quite naturally, as in the so-called ‘Marienthal Study’, for example (see box). It was only in the 1950s that the methodological dispute arose that ended up defining the two approaches as inherently different. “The separation that resulted is artificial and unproductive”, says Mottier. This is why she finds their reunification to be a positive development.

Mixed-method projects are more complicated because their research design is more complex and communication between the two sides is more demanding. But the effort is worth it, says Diana Baumgarten, a research associate at the Centre for Gender Studies at the University of Basel, who practises qualitative research, but has already worked together with quantitative researchers in several projects. Both sides are constantly struggling for mutual recognition, but you learn a lot from each other, she says. And there are bigger gains in knowledge involved: “In the end, it’s like wearing a different set of spectacles, and you can see better through them than you could before”.