The daily research routine

Things change

For two months, life stood still. The lockdown also affected researchers in all manner of ways. Some grasped it as an opportunity, while others had to make traumatic decisions. We tell five stories from a time of extremes.

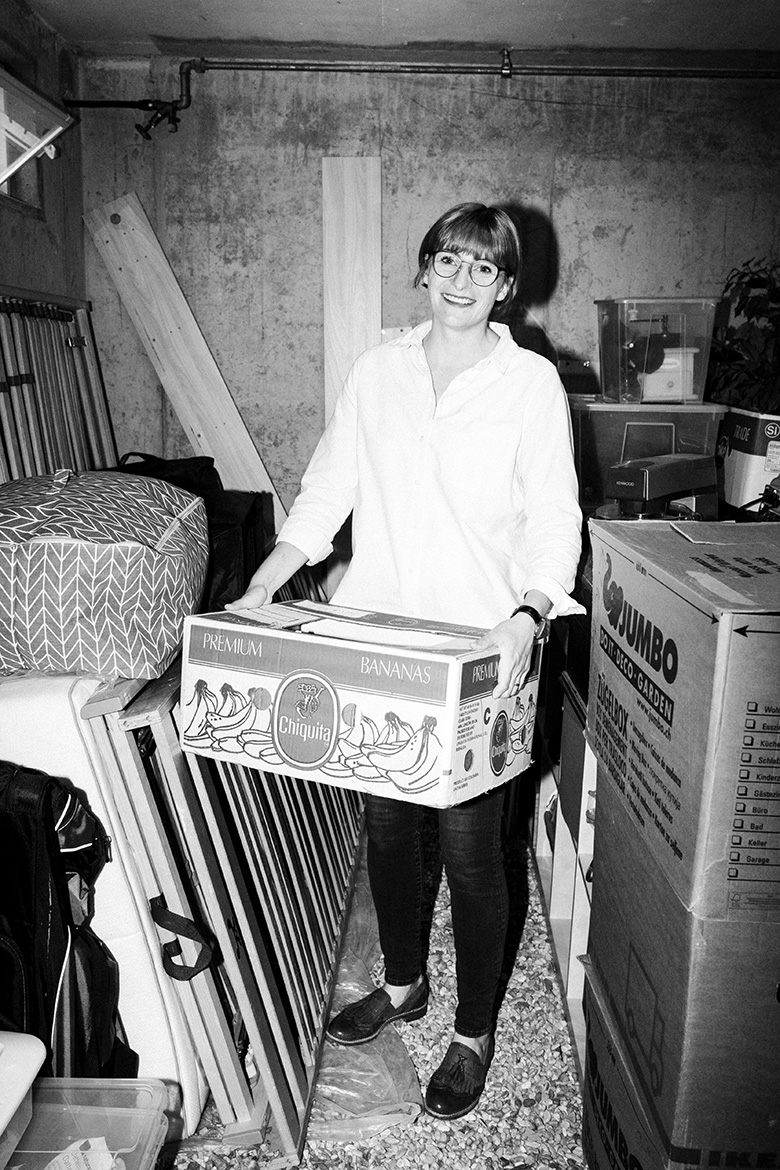

Research visit postponed because of the travel ban | Image: Fabian Hugo

“I couldn’t open the borders. All I could do was wait”.

“We had just cancelled the lease on our apartment and resigned from our jobs when the Federal Council announced the lockdown. It wasn’t completely unexpected, but when the USA closed its borders too, it hit me pretty hard. Had we just put our lives in Switzerland on hold without being able to start our new lives over there? I was supposed to have started my two-year postdoc Mobility Fellowship at Michigan State University in the USA on 1 June, where I was going to continue with my present research projects. I am investigating how personality, health and personal wellbeing influence each other, especially in close relationships. What was most difficult of all in those months was feeling so powerless. I couldn’t open embassies or borders. All I could do was wait.

I even wondered once whether or not I should send President Trump a tweet. But it wouldn’t have achieved anything really. Of course I could have started working from home, but that’s not the point of a research visit abroad. Luckily, everyone involved reacted really well. I was able to work longer than planned at the University of Basel, my husband was also able to extend his work contract two more times, and we are at present living with our little boy in two rooms in the home of my parents-in-law. It’s pretty cramped, but in mid-September, we finally got good news from the embassy: we’ll be able to leave for the USA in November.

Emergency deployment in the Locarno Hospital. | Image: Sébastien Agnetti

“I didn’t think it was ethical to continue my research”.

“I was reading a lot of news about Covid-19 and I could see that the situation in Switzerland was becoming explosive. As I’m from Ticino, I also read Italian newspapers, and there it was even worse. I didn’t think it was ethical to continue my research on databases in Paris. One evening, a former medical colleague contacted me to tell me that it was time to leave the laboratory and go into the field. That was one of the triggering factors.

“I went to Locarno. That’s where my parents live, and it was in the local hospital that the people of Ticino with Covid were being treated. I knew the hospital from my schooldays, because I had worked there after completing my education. Normally there are perhaps five patients who are intubated in the intensive care unit. By this time there were 70! It was somewhat emotional. But as a doctor you are used to going in and getting down to work. So I supervised the infectious diseases and hospital hygiene departments from March to May. As there was only one other infectious disease specialist in this hospital, my knowledge was well appreciated. I am very happy that I put my research on hold and did something for the people of Ticino. In a situation like this, you help if you can”.

Caught in the Arctic. | Image: Ornella Cacace

“Some of us found being stuck difficult”.

“And then we realised that we were stuck up here, in the midst of the polar ice. The team that was supposed to replace us was not going to come – couldn’t come – because the pandemic meant no ships were travelling, and no planes flying. When I set off on my big adventure in late January – a research trip to the icebreaker ‘Polarstern’ – people were already talking about the virus, but somehow it was still far away. I finally arrived on the Polarstern in early March, and we heard increasingly disturbing reports while we were still travelling. But when the sun rose again for the first time after the long polar night, it was so breathtakingly beautiful that I initially just concentrated on my research there.

Then the large ice floe broke on which our helicopter was supposed to land, and the chances of our being replaced receded into the distance. We were 40 to 50 researchers and 40 crew. Actually, the mood was very good. But some of us found being stuck difficult, especially those who had children at home. It wasn’t so bad for me. I loved my work there. I went out onto the ice every day in order to take snow samples. I analysed the microstructures and the chemical properties of the snow cover on the sea ice. I wasn’t worried about our supplies. Only our toothpaste was in danger of running out. I liked it so much that when we were finally able to be relieved in June, I actually decided to add on another two months”.

Premature euthanasia on hundreds of mice. | Image: Anoush Abrar

“We had to euthanise the animals”.

“In mid-March, the EPFL animal house had to act quickly in a very uncertain context. There was talk of closing the borders, yet there was a food delivery expected from abroad and many of our animal keepers had to cross the border to come to work. Lockdown was going to delay our animal experiments, which is incompatible with our protocols. They require a very specific age for the mice. Together with our colleagues at the Center of PhenoGenomics, we had to make the difficult decision to euthanise the least indispensable animals. In my laboratory, we had to sacrifice half of our mice. The first two weeks were very difficult. I had to decide which projects had priority and which projects had to be stopped, which meant euthanising the mice in question. I found it traumatic.

My researchers were devastated. It was very sad from a moral and ethical point of view with regard to the mice, a professional disaster for my team, and a financial mess. Because of this, some researchers will not be able to complete their project even though they are brilliant and represent the next generation. My goal now is to restart the projects that have been stopped, although some have to start from scratch. Raising rodents for research can take up to a year. I hope that institutions will realise that some laboratories have suffered much greater losses than others, and will grant extensions to the researchers involved. I will fight for that”.

Data scientist Stuart Grange checks an air inlet. | Image: Désirée Good

“We got a small foretaste of what the situation might look like in Europe in 20 years’ time”.

“I’ve been far away from home for more than five years now. That has never bothered me, but it changed during the pandemic. Normally, if I have to, I know can get on a plane quickly and reach home within a reasonable period of time. But that certainty has disappeared. Now I feel somehow cut off from everything that is happening at home in New Zealand. However, I was incredibly busy during the lockdown, and that distracted me. I am a data scientist at Empa, and took on an additional research project. In late March, I began investigating the impact of the societal standstill on air quality in Switzerland. The fact that traffic was vastly reduced indeed had an impact, at least in the urban areas. Nitrogen dioxide levels dropped by some 20 percent. However, we were surprised that ozone levels also rose by 20 percent.

We know that these two values influence each other, but we didn’t expect ozone levels to rise so much, despite there being far less traffic. The weather also played a role, however. We had unusually sunny days in April, which presumably influenced the ozone levels too. We got a small foretaste of what the situation might look like in Europe in 20 years’ time. We will soon be publishing our work in a journal, but I think it’s important to take enough time over this. Too many studies of the past months have seemed rushed to me”.