Feature: Diversity in the academy

The boundaries of anti-discrimination

From personal aggrievement to apocalyptic visions: Five researchers criticise the current insistence on diversity and discuss its collateral damage.

Every human being should have the same opportunities for higher education and a career in the academy. Their intellectual gifts alone should be the deciding factor. Most people in science and scholarship today would subscribe to this ideal. But as soon as it’s a matter of how to realise it, people’s opinions diverge.

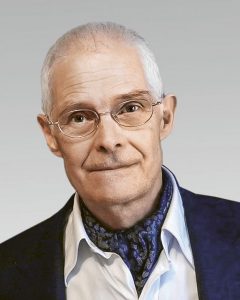

“Pigeon-holing is perpetuated”

Florian Coulmas, some people find it presumptuous when you, white and male, express an opinion on those who are disadvantaged.

Florian Coulmas: Of course I can’t adopt the perspective of someone from a minority group. I don’t know what it’s like for someone who’s black to walk through the streets of Zurich. But I do have certain ideal notions that I can talk about.

You are critical of diversity measures at universities. What bothers you about them?

I just got a letter today from our Vice-Rector, who wants us to nominate someone for our university’s ‘Diversity Prize’. That’s well-intentioned, but what exactly are they supposed to have achieved for them to be nominated? It’s a sad commentary on the University, which simply wants to signal that it’s following the diversity trends coming from the USA. That’s the wrong way to do things. If there is a suspected case of disadvantage because of someone’s race, gender or some other criterion that is irrelevant to science, then university management has to step in – whether the case in question is about marks allocated, tasks assigned, or a job application.

Perhaps diversity prizes are not very effective, but they don’t harm anyone.

Such initiatives simply perpetuate the pigeon-holing of people. I think that’s disastrous, and I know of affected people who have complained about it.

“People just look different”

Peter Boghossian, do you know the definition of diversity?

I would say: it’s a nice word. Also, safe spaces, inclusion and equity all sound positive. But diversity does not mean what most people think it means. It does not mean intellectual diversity. Academics who work in this domain are using a peculiar definition of the word diversity. In practice, it means that people on a panel look different, but they advocate the same stance. So it actually means homogeneity of thought. People have been hoodwinked by a nice sounding word. Take inclusion: An inclusive space is one that makes people feel welcome. But this means restricting speech; otherwise some people would not feel welcome. The content of some speech is considered to be literal violence. This makes it difficult for conservatives – though certainly not just them – as much of their speech is perceived to be violent.

So in the end, all the people on those panels have to be left-leaning?

No. It is not even enough to be just left-wing, you also have to be woke.

Are you against diversity of people at universities?

No, I am one hundred percent for it. I champion intellectual and ideological diversity. The University should be the place for difficult conversations – truth has to be in the front and centre.

“They wanted to remove undesirable books”

Matthias Revers, some claim that lecturers should no longer be allowed to teach if they believe that men and women have different abilities based on their respective gender. Of all the students in your study who were asked to agree or disagree with this statement, 64 percent agreed. Why is that?

Matthias Revers: I can only surmise the reasons. The differences between men and women are actually indisputable, but it depends what you understand by this. Of course it’s not true that women can’t become mathematicians just because they can bear children. But the crassest example we found in our study was that up to a third of students also wanted to remove undesirable books from the library. That’s shocking.

Where do such drastic demands originate?

The underlying problem is polarisation. It’s especially problematical if you can’t see the affected people face to face. We are quick to form judgements, and speakers are sorted into different camps: they’re Islamophobic, sexist or whatever. The questions we asked in our study triggered strong reactions.

Can such a discursive climate also become a problem for the victims of discrimination?

The problem comes when more differentiated opinions are no longer heard. Such as some feminists who criticise wearing headscarves. For example, students wanted to prevent the ethnologist Susanne Schröter in Frankfurt from holding an event about headscarves, and even demanded that she be sacked. Thankfully, the event still took place.

“We need practical measures”

Franciska Krings, what exactly do you mean when you talk about gender equality? Do you mean equal opportunities, or equal representation on all levels?

Franciska Krings: If we’re talking about the equal opportunities prescribed by law, it’s also about what the actual results look like. Of course, there is always room for manoeuvre when defining the concept of equality. If women don’t make progress in their careers, whose job is it to adapt? The women or the system? There are differences between the genders; for example, if you look at women and men who are equally talented, you’ll find that the women tend to avoid competitive situations. At our university, we were unable to get certain excellent candidates for professorships because their husbands were not prepared to forgo their own career. It could help in such cases if you could make a career offer to both at the same time. That would help women, and wouldn’t disadvantage the men.

You say that prejudice training hardly has any long-term, sustainable impact. So is it primarily a PR measure?

I can’t give you a good answer here. The money could certainly be better invested elsewhere. Besides making dual career offers, we also need practical things such as more opportunities for childcare and more changing tables on campus.

Can positive discrimination lead to resentment – perhaps among young men, who don’t believe that they themselves engage in any kind of discrimination?

Yes, that’s certainly the case. That’s why I’m against harsh measures such as quotas. It is an utter dilemma that can’t be solved on a case-by-case basis. However, structured action by HR departments can have a big impact – perhaps by recruiting specific women, or by organising booths or workshops at university career days that are aimed at women in particular.

“Categorical thinking is problematic”

Thomas Köllen, what is it that bothers you about the promotion of women?

Thomas Köllen: It’s an important aspect, but it’s not everything. Students and staff have all manner of backgrounds. There is no reason to look at just one aspect of diversity. Nor is there any reason to maintain the current hierarchisation, which makes promoting women the most important issue. If we take a holistic view of diversity, then you have to consider everything that gives person A an advantage over person B, in all possible dimensions of diversity.

How can all these diverse manifestations be promoted at the same time?

I find categorical thinking fundamentally problematical. It means people will always fall between the cracks. We should think in multidimensional terms, and contextualise individual cases. We should ask ourselves why women often have poorer access to resources. We could also adapt support to match the degree of need involved. That would mean a single father could benefit – or a man who is caring for dying parents.

Photos: zVg