SOCIETY

The constellation of assisted suicide

In Switzerland, assisted suicide is a well-organised process involving a multitude of people. Relatives, doctors and police officers have well-defined roles, which are not always easy to play.

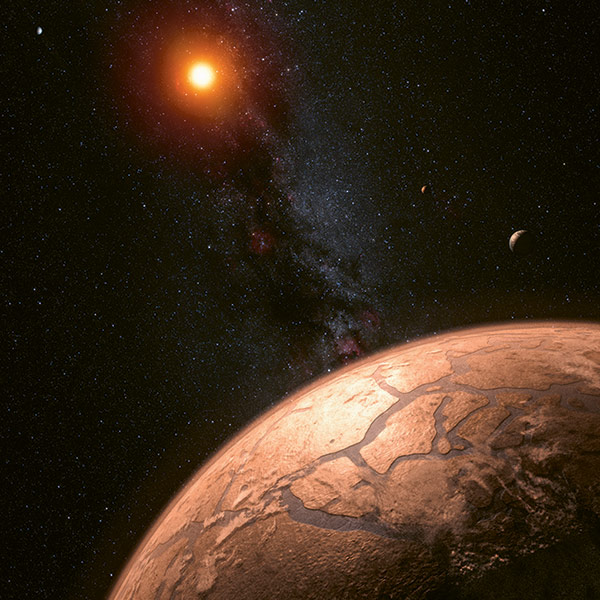

What happens after a voluntary death? And how do the people involved experience an assisted suicide? When someone leaves this world with the aid of a euthanasia organisation, it also has an impact on their relatives, the police and hospital. | Photo: EyeEm/Getty Images

The number of assisted suicides in Switzerland is on the rise. In 2018 they accounted for 1.8 percent of deaths (1,176 cases) among the resident population, according to the latest figures from the Federal Statistical Office (FSO). The debate surrounding this practice focuses mainly on its ethical aspects. Less is said about all the people involved in each of these prepared deaths: relatives, carers, social workers, pharmacists, assistants from associations specialising in deaths, police officers, forensic doctors, public prosecutors, undertakers, etc. Recent research has shed light on the role of all these behind-the-scenes actors and shows what assisted suicide means to them.

On the front line, the family is subject to high expectations. “Any assisted suicide needs to be legitimised and legalised. Legitimisation requires the support of the family”, says Murielle Pott, a professor at the Haute école de santé Vaud (HESAV) and a specialist in thanatology and palliative care. For her, “the roles played by relatives are very special. Among other things, they must help the person to live so that he or she may then die”. In Switzerland, direct active euthanasia is illegal and in order to have recourse to assisted suicide, one must be able to absorb the lethal substance oneself and to have discernment.

“Taken hostage”

For one of her research projects, Pott conducted interviews with 29 relatives of people who had resorted to assisted suicide. According to her results, the process is “always very painful”, but everything is done to make this last stage of life peaceful. Relatives opposed to the idea of assisted suicide are shunned. “A wife relates her husband’s words about it being him who chooses the people he wants to have contact with in the last days of his life. ‘Naggers’ are kept at a distance”. The only negotiable element is the time frame. They try to squeeze in a few days or weeks before the death of their loved one. In case of disagreement, there may be threats. One woman described how her husband had said to her: “The assault rifle is here. Either you help me or I’ll do it myself”.

It’s not just relatives who can be shaken up by the ticking clock. In the vast majority of cases, assisted suicides take place at home. But sometimes they are organised in care homes, day centres or hospitals (see box). In these cases, an assistant from Exit or a similar association intervenes on site. Everyone has to agree on this. And it’s not easy. “In hospitals, people wishing to resort to assisted suicide sometimes express a certain urgency that medical staff do not understand”, says Ralf Jox, a co-holder of the chair in geriatric palliative care at the University Hospital of Vaud (CHUV) and a professor of medical ethics at the University of Lausanne (UNIL). He participated in a recent study on clinicians’ attitudes towards assisted suicide.

In a vast study on assisted suicide in Switzerland, one doctor in charge of a palliative care unit in a regional hospital had this to say: “We are held hostage in terms of the timing, because the rhythm of the hospital and the rhythm of the emergency of a request for assisted suicide are not compatible”. The study was carried out between September 2017 and November 2020 in the French-speaking part of Switzerland plus the Basel region, and it describes for the first time the entire system, including all those involved ante and post mortem, using fieldwork and interviews. “One of the fears of carers is that the handling of this type of case, which requires a lot of energy, will be to the detriment of the other people in hospital”, says the anthropologist Marc-Antoine Berthod, a professor at the Haute école de travail social et de la santé Lausanne (HETSL) and a lead researcher in the study.

A sense of failure

A forthcoming survey of thousands of employees at CHUV and the University Hospital of Geneva (HUG), to which Jox contributed, shows that, in general, doctors are “a little more reluctant” than other health professionals to participate in assisted suicide. “Many doctors see failure in a person who wants to die or to relinquish the fight against illness. In addition, they take responsibility for the process (Ed., establishing medical certificates, capacity of discernment, prescribing the lethal solution) and must ensure that there is no external pressure, especially from the family”.

The conclusion of the study initiated by Berthod and his colleagues is that, despite the reservations that may be expressed, the Swiss model of assisted suicide is globally accepted by all involved. This is perhaps one of the most significant results of this ground-breaking research, which was the subject of a book published this spring (La mort appréciée. L’assistance au suicide en Suisse, Antipodes). “The people involved in the process try to put aside their personal opinion as much as possible because they are part of a chain and have confidence in the whole system, even if they aren’t familiar with all the stages”, says Berthod. “At each level, we make sure that things are done properly”. It’s like the police officer quoted in the study who sees all the procedures to be carried out after an assisted suicide as a way of “making sure that we stay within the framework”. For him, assisted suicides are calmer affairs, because there’s a readiness involved: the people who die were suffering.