FEATURE: IN VIRTUAL SPACE

Moira

A short story

It’s just like it’s always been, waking up. It’s hard, momentarily, the body’s slow to respond. As I move to the edge of the bed, the sheet slides off my skin with a soft shudder. A subdued light falls from a ceiling panel, gradually increasing in intensity. There are no windows, nor are there any shiny metal surfaces, meaning the ordeal of looking in a mirror is waiting for me on the other side of the solitary door, which remains closed.

I try to come to terms with this reality, to understand what that means. I look at my supple, pale hands. They’re no different than my recollections of them. This stain on my wrist, those old wrinkles that gambol across my knuckles. There are no scars, of course. Without thinking twice, I lift my hand to the top of my skull and finger the opening to my neural port: the large socket that connects my brain to the real world. I can feel it, so warm, so vibrant, so deliciously intrusive. It’s fused to the bone and, running my finger around it, I see there’s no feeling at all.

Today I turn fifteen years old. My coming-of-age ritual will begin just a few minutes from now. Then I’ll discover my true face, here in the world of my body, far from my comfort zone.

I’m overwhelmed by dizziness and the need to gather my wits.

I reach to my forearm and pinch a fold of skin between thumb and forefinger, squeezing harder and harder. It’s not tempered by a pain filter, I could go on until it hurts... But releasing my grip, I see my nails have left purplish marks.

So, this is my body, the temple of my consciousness. Something I’ve always thought of as a protective shell, a cosy cocoon of fat, muscle and cartilage. Yet here is my head, firmly attached to the top of my spine. I fill it the same way I do the avatars of the real world.

I mean my real world, where there’s almost no pain, no hunger, no sickness, no frailty, no risk, no accidents, no bad smells, no tears, where nothing tastes bad and where there are no bodily functions, no eating, drinking, defecating, sweating, washing, moving, or working. And death is a just discreet erasure with a painful footprint.

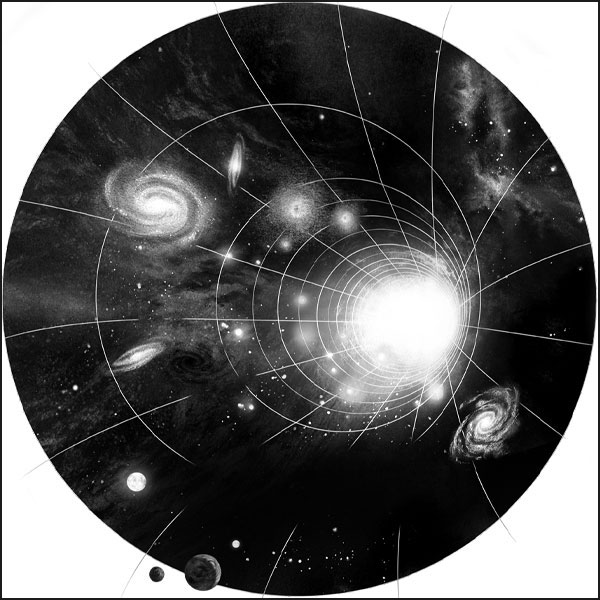

In my real world, I can fly, or change shape, or connect directly through my consciousness to experience the emotions of others, I can modify my environment... Once this ordeal is over, I’ll return there, having become an adult, and then I’ll have free choice. No longer a child, I’ll be no longer obliged to learn suffering and physiological control on the basis that, following a hypothetical decision, I’ll return there one day to grow old... Why would I choose this original reality, which serves only to keep my organs alive? When there’s much more reality in my world, more vastness, more things worthy of interest than in this hostile wasteland of the senses, where I drag my body like an old Martian rover decaying, piece by piece, before petering out, motionless in the midst of a cold and rusty immensity.

Now, finally, I’m an adult, and the future holds my dreams! I can spend every day flying, no more learning to walk, to defecate, to chew, to change this face, the face that I’ll discover presently, seeing it in the flesh, hopefully, for the last time.

There’s pain in my buttocks and lower back, from having sat still too long as thoughts ricochet in and out of the furthest corners of my mind. It’s always the same, my body recalls its demands. It’s just that now, all of these pieces of information arriving in my brain are authentic, there’s no more intermediaries, no more interfaces. And the pain is already there, hardly a minute having passed.

Like the rest of humanity, I grew up in a vat. Now, for the first time, the fluids that have been bathing my body have been drained. Gone are the feeding tubes, the neural lattice, and the delicate network of nanotechnology that had bandaged my flesh since birth.

It’s a second birth.

I’d have liked my godparents to be here, but this is actually a moment to connect with the self. After all, the first few minutes of original reality are in the first person.

I breath in sharply and straighten my torso, pushing down on the edge of the mattress to stand up. It’s as compliant as it was waking up, as it is touching or breathing. Once stood up, I realise nothing remarkable has happened and that the pain that was tugging at my back is subsiding. I have never shown off my original body like I do today. A sudden, dull and irrational fear floods my being: a fear of walking, of falling, of my head smashing against the ground, of causing damage to this very precious and very permanent vehicle.

Risk is everlasting in this world. My life hangs in the balance as each second passes.

I draw more air into my lungs and take three steps forward. It’s simple and uncomplicated. The obedience of my limbs is like it is in my reality. The sensations are the same, the mechanical responses harbour no surprises.

As I approach the door, it vanishes. Beyond there’s another room, larger but just as bare. At its centre, there’s a lectern covered in black cloth, and, behind it, a curtain.

I naïvely hope it’s just a simulation. I click my heels to enter flight mode, maybe the ceiling will explode in a shower of pixels and then I’ll pierce the heavens like a flaming comet, but no, instead, nothing happens. My body and I are petrified, a rock worn down by the wind in the sandy desert. I can’t access an interface, the music that usually accompanies my travels is gone, and there are no sound effects for my actions. There’s only me and reality, stifled in the silence of the senses, joined in this fierce and deterministic communion of feeling.

I step forward and, taking the velvety cloth with one hand, unveil a mirror.

In it, I see a face, its forehead framed by tight black curls. The mouth has well-defined lips, tailored for kissing and savouring sugary puddings. As I breath in, the nostrils flare. The eyes are limpid, their centres coal-black nuggets, and their frame a dark wood. Although my skin is matt and ashen, there’s something striking about the intensity of my gaze.

My mind conjures images of my dormant body being incubated by machines, whereas I am now somewhere else, living my life in a place impossible to pinpoint, a space that has no material foundations, but yet which is so real, I call it my home.

“Moira … ”.

My mouth has just uttered its first word, and I’m reassured to hear my name. The tone of my voice is the same. My ability to hear, from inside my head, has been perfectly reproduced.

I peel my eyes away from my face, turning to pick up an apple sat beside the mirror – placed there by whom I wonder. Who wants to live in this world? Who takes care of the daily chores? Is it a person who finds enough meaning in the simple activities of which the body is capable? Or is it thoughtful machines of the kind to set down an apple upon an algorithmic whim?

I observe it more carefully. It’s firm and round but rough to the touch. There are small black dots sprinkled across its pale-green sides, and where it’s been sitting, there’s a brown spot. Never before had I seen such detail on an apple. I imagine placing a thin slice of it under the hard light of a microscope: the cells would look like a wall of blistered bricks mortared with ultraviolet lime. This empirical discovery is so very simple, yet where I come from it would be impossible.

The lectern holding the mirror is old. I can see this in the lines running through the wood. I kneel down and inspect what turns out to be a single upright element, carved to represent spiralling plants growing out of clawed feet and up into the inflorescence upon which the mirror rests. One side of the stand has scratches, showing where it was manhandled and scraped against a wall. One of the feet is pitted with small marks, as if a child had stabbed it repeatedly with a screwdriver. Together the many marks tell a story that was imperceptible at first sight.

That’s when, all of a sudden, everything begins to makes sense: the wrinkles, the scars, the frailties, the punches, the inertia, the ranges of movement, even the very use of the limbs, muscles and nerves, all of which imprint over time, experiences, habits and accidents… they all leave an unalterable trace.

In my world, I can change my avatar on demand. Here, it’s the opposite: learning is etched out in real time, tattooed, engraved on the body.

There, if I want to climb a mountain, I can add on a few limbs, turn myself into an ibex, and everything becomes simple, the experience becomes a pleasure, and from there a performance. Here, climbing a mountain may cost me my life, even with the right preparation, skills and equipment.

Dreams used to belong to childhood; the adult life consisted of constraints. Now everything is flipped on its head: the child’s life is a series of constraints aimed at learning how to use an original body, whereas the adult’s life is now a long, potent and lucid dream.

I was born wanting to free myself, to embrace the never-ending illusion that was my world, with its limitless, harm-free discoveries that multiply constantly along hyperbolic curves inside narcissistic bubbles inflated by the self, by others, by these overlapping perspectives that feed off of and then abandon each other.

And so, it is here – facing the ultimate constraint head-on – that I come to terms with the extent and incredible finesse of body-based exploration, the perpetual risk, the slowness of the senses and the days, having to worry about husbanding my energy, my activity and my rest, bending them to match the inherent rhythms of a planet spinning on its axis and dividing time into light and dark.

I’m overcome by a surge of unruly delight, by the crazy idea that I can step into a life like this, hold onto the fragility of each passing moment. A fire has been kindled within me by my having contemplated a finite universe, one where wear and tear reigns and one where time leaves a patina whose form is narrative.

I want to see the sky.

I move beyond the lectern and pull aside the curtain. Behind it there’s a window and I’m instantly blinded by the sun. While I wait for my eyes to adjust to its brightness, I scan the corners of the window pane, where there are myriad fingerprints on the glass, illuminated by the pastel light of what I suppose is dawn.

Here, I’ll never be alone. Dreams can wait. They won’t go away. Not yet.

With a smile of excitement, I bite into the apple, ready to discover a new world.

Vincent Gessler is a science-fiction author and lives in Geneva. His first novel, Cygnis, was awarded two French literary prizes in 2010.