ALCOHOL THERAPY

Motivational therapy to beat the binge

There are many different ideas about how to treat addiction. A research group in Lausanne wanted more precise information, and so has been testing brief motivational interventions at an emergency department for four years now. The initial results are encouraging.

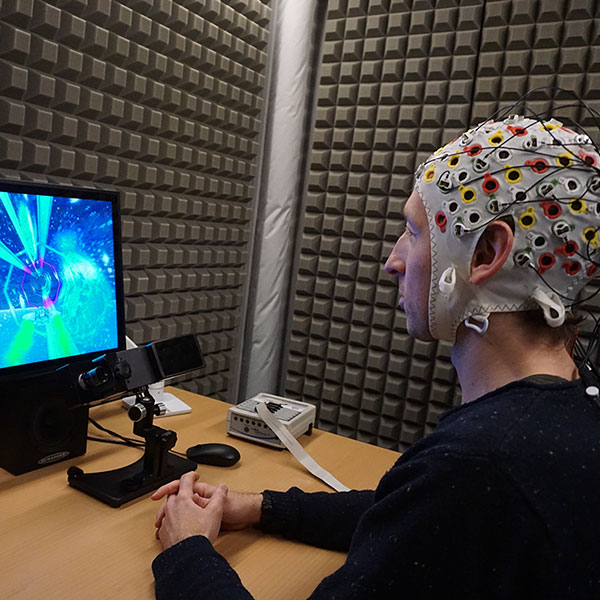

Young binge drinkers often land in the ER. But there’s a therapy for them that can improve their situation without any moralising. | Photo: Marius Eckert

Time and again, binge drinking lands young adults in the emergency room – either because they’ve had an accident, or because they’ve got alcohol poisoning. According to Sucht Schweiz – the Swiss national competence centre for addition – an excess of alcohol is responsible for more than ten percent of deaths among this age group. But since hardly any of these young people embark on therapy for addiction, researchers have begun to focus their attention on the emergency rooms of hospitals. At present, one popular option is so-called brief motivational interventions. This is a dialogue between the young person and an expert that takes place without any moralising. Together with the patient, an assessment is made about whether they can change their way of life – and if so, what concrete steps they might be able to take.

At present, research findings are contradictory about whether or not these brief motivational interventions are really effective, and whether or not they can indeed reduce binge drinking. It is not easy to investigate the impact of such a complex form of therapy. All the same, Jacques Gaume and his team from Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) are getting to grips with the topic. Together with their hospital’s ER, they have designed a study to assess its efficacy.

Comparisons with and without empathy

The first question that arose was: what possibilities for comparison exist for this new form of intervention? “Normally, alcoholism isn’t treated at emergency departments”, says Gaume. “In Lausanne, we have a basic model that offers minimal consultation plus recommendations for specialised therapy”. But how things actually proceed depends on the workload of the people involved. In order to be able to make meaningful comparisons, the treatment offered had to be standardised for purposes of the study. This would allow the researchers to establish a clear differentiation between the two types of intervention. “In order to do this, we had to remove everything from our basic model that entailed empathy”.

In a brief motivational intervention, however, empathy is crucial. First, a relationship is established between the therapist and the patient. Together, they have to register what the problem is, without any confrontation occurring. Then they have a dialogue about how the situation could be improved. And in a third part, they plan the next steps that the patient would like to take. These steps are described as concretely as possible. The patient is then given a written summary of what they have discussed. If the patient so desires, the therapist will subsequently contact them by phone to ask about their situation and their development. The therapist calls them after a week, after a month, and after three months.

This sophisticated dialogue plan was tested with ten patients in a preliminary study. It was then optimised and the precise study protocol was published. The actual study itself recruited 344 patients and divided them randomly into two groups. The one received the basic short consultation without empathy, while the other group was given the brief motivational intervention.

They have yet to evaluate all the data, but the principal result is already clear: “It works. We’ve been able to stabilise the number of binge-drinking episodes on a lower level”, says Gaume. ‘Binge drinking’ is defined as having more than six drinks of alcohol at one time. ‘Stabilising’ here means that there are fewer such episodes twelve months later than without the motivational therapy. Those people who were given the basic short consultation had an average of 3.4 episodes of binge drinking during the first month after the intervention, rising to 5.1 episodes in the twelfth month afterwards. With the motivational therapy, the increase was considerably smaller: from 3.7 episodes in the first month to just 4.1 episodes in the twelfth month. So the new treatment does seem to have a more long-lasting impact.

The results of the study have not yet been published. Erik von Elm is the head of the Swiss subsidiary of the Cochrane Collaboration, which campaigns for an evidence-based healthcare system, and he only has praise for the systematic approach employed by the study. He adds that it should have long been standard procedure for study results to be published, independently of how they turn out. The fact that this study has been running since 2016 is also proof of just how thoroughly it is being conducted. Von Elm says: “Clinical research takes time if it’s to be done well, but the paucity of funding opportunities means this isn’t always possible – and that’s when compromises are made”.