BIOLOGY/DOMESTICATION

The complex history of human-canine relations in the Americas

Humans who populated the Americas never domesticated local wild canines. Palaeontologists have put forward certain hypotheses to explain this.

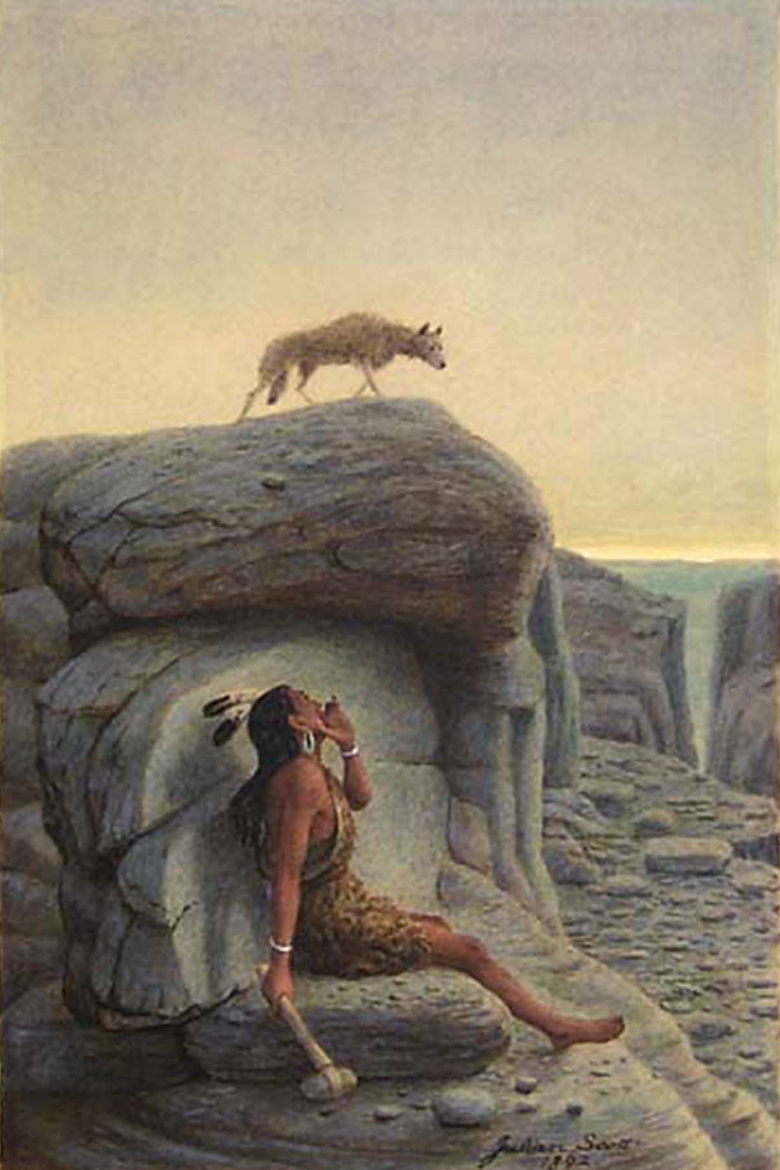

How the 19th-century American artist Julian Scott imagined early interaction between humans and the wolf. | Image: Julian Scott

Humans colonised the American continent 15,000 years ago, together with their dogs. Today’s domestic dogs in the region are all descendants of the Eurasian grey wolf. No species of wild canine was domesticated there. Marcelo Sanchez, a palaeontologist at the University of Zurich, has confirmed this by means of genetic analyses of archaeological bones. Together with Valentina Segura of CONICET, Argentina’s national scientific and technical research council, he has examined the reasons why American populations were unable to domesticate one or more of the nineteen species of wild canines present on the continent.

Two species of domesticated canines

The study analyses in detail the biological attributes that make domestication possible for each of the wild canine species: e.g., docility, dietary flexibility and the ability to reproduce in captivity. According to the scientists, the coyote and the bush dog possess these qualities. So why haven’t they been domesticated? The aggressiveness of young coyotes and the propensity of the bush dog to get sick might be clues.

Another explanation lies in the particular world views of certain populations in the Amazon basin, an area in which archaeology has not - for the moment - demonstrated the presence of domesticated dogs before the end of the 19th century. “Anthropological research shows how ideas about relations between living beings in these societies make domestication a non-starter”, says Sanchez. However, this argument cannot be extended to the entire American continent, which is characterised by a great diversity of cultures and world views. For Sanchez, it is likely that “since the populations of the Americas already owned dogs, they did not feel the need to domesticate other species”.

The Eurasian grey wolf has therefore won the prize for domestication of canines. “We can talk about luck to a certain extent”, says Sanchez. “But the biological attributes of the grey wolf, as well as the distribution of the species in regions experiencing strong demographic growth during the Palaeolithic, are certainly to blame”. And the domestication of the only grey wolf among the canines should not make us forget the numerous and complex relationships woven by humans with other species of wild canines, a phenomenon that is particularly remarkable in the Americas and which has left numerous archaeological traces.

Intense connections with wolves, coyotes and foxes

Bones of wolves, coyotes and foxes have been found in graves. These animals have also been the subject of symbolic representations. And the adoption of litters of these species is a practice that continues to this day. The diversity of degrees of integration of wild canines in these societies shows that there are many possible relationships between humans and animals, well beyond a rigid duality between domestication and wildness”, says Aurélie Manin, a zooarchaeologist at Oxford University. “The most common definition of domestication, which involves controlling the reproduction of a species for utilitarian purposes, is inherited from 19th-century Western culture. Many societies in history and in today’s world do not share this otherwise highly anthropocentric definition”.

Can we affirm that the pre-Columbian societies had domesticated these wild canines as we understand the concept in the West? The answer is far from simple, especially because it is often not easy to distinguish among the bones of canines. But research is progressing: Manin has recently developed a method for analysing canine dentition that allows us to distinguish canine species with greater certainty.