Feature: Patient data

In sickness and in health

Swiss health policy focuses not on the collective, but on the individual. We lack an understanding of public health – which is also why we also lack important data for research. We take a look at why this is the case in Switzerland.

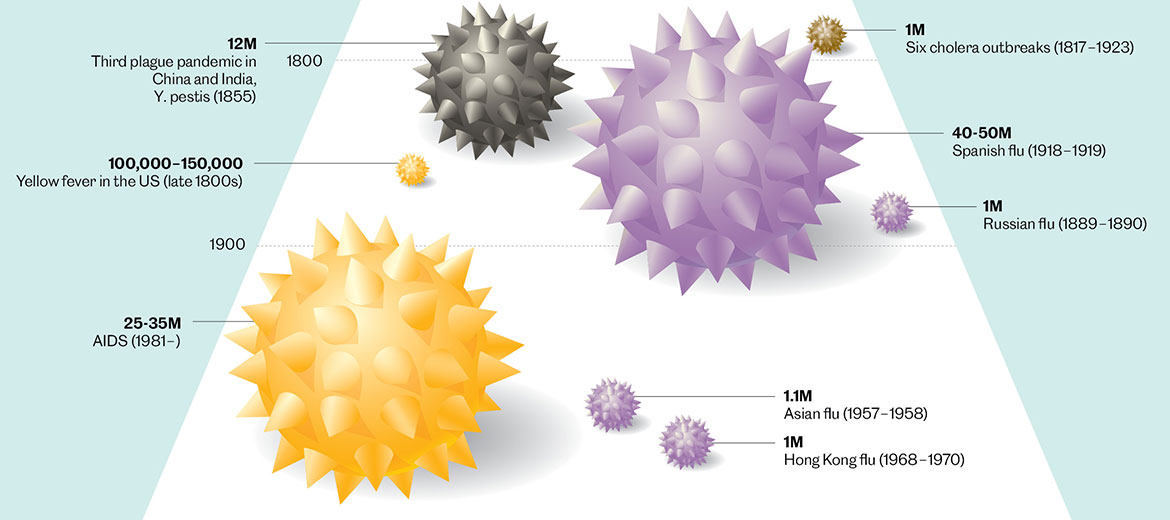

SARS-CoV-2 has made it clear yet again that infectious diseases are killers. Other pathogens have also brought death to many, such as cholera in the 19th century, Spanish flu at the close of the First World War and AIDS in the 1980s. | Graphic: data by Nicholas Le Pan; design by Harrison Schell; adapted by Oculus Illustration

In November 2021, a chart in the Financial Times of London went viral. It showed the percentage of unvaccinated people in various Western European countries. The predominantly German-speaking countries of Austria, Switzerland and Germany were clearly in the ‘lead’, with well over 20 percent unvaccinated. The difference was striking between them and Portugal or Iceland, for example, where under two percent were unvaccinated. That graph obviously hit a nerve: under the hashtag ‘#DACHSchaden’, Germans, Austrians and the Swiss (D, A, CH, respectively) shared their horror at the low vaccination rate in their respective countries.

Various theories circulated about the possible reasons. An editor at Spiegel magazine in Germany interpreted these statistics as “late consequences of German Romanticism: anthroposophy, homeopathy, anti-vaxxers”. The journalists of the Financial Times suggested right-wing, populist Covid-scepticism as a reason.

But this low vaccination rate is presumably just one link in a long chain of problems, the roots of which can be found in a lack of acceptance of the idea of ‘public health’. In contrast to individual medicine, public health deals with the health of the whole population and aims to maintain and improve it through organised, community efforts.

Prevention as fundamentalism

This basic problem was clearly revealed in the anti-Covid strategy of the Swiss Federal Council: “From the moment when all the willing are vaccinated, the [anti-Covid] measures can no longer be justified”, said the health minister Alain Berset time and again in the spring of 2021, almost like a mantra. This statement was in tune with the message that every person is responsible for their own health, and that getting vaccinated against Covid-19 is a personal matter.

The federal government’s vaccination campaign was similarly designed in a liberal manner. Other countries automatically sent people a vaccination date while allowing them the possibility of actively opting out, or simply imposed compulsory vaccinations. The Swiss authorities, in contrast, limited themselves to providing information and appealing to people’s sense of solidarity.

By November 2021 at the latest, it became clear that this strategy was not working: the vaccination rate remained at a low level and the number of infections was increasing rapidly. Once again, we were faced with a horror scenario in which ICUs could soon have become completely full.

Whether it’s low vaccination rates, a predilection for sending data by old-fashioned fax, or a cantonal patchwork of preventive measures: the Covid pandemic ruthlessly revealed Switzerland’s basic lack of any real understanding of public health, let alone the structures that would be necessary to implement a comprehensive approach to it.

Apart from the revised Epidemics Act, which has only been in force since 2013, there is hardly any legal framework. For example, several drafts for a national law on preventive measures and health promotion were abandoned in parliament, the most recent case being in 2012. Politicians from the right warned against so-called ‘preventive fundamentalism’ that would supposedly make people sick, not healthy. In Switzerland, it is probably such attitudes that over the course of many years have slowed both the development of public health as a scientific discipline and the establishment of any concomitant practices.

Public health needs good data, something in short supply here, as the Swiss Society for Public Health already pointed out in 2013. For example, we lack long-term studies with 100,000 or more participants that would make it possible to recognise the causes and harbingers of chronic diseases, e.g., diabetes, cancer or dementia, and to identify approaches for their effective prevention. Datasets on diagnoses, therapies and costs are available, but they can hardly be used for public health because they cannot be accessed, linked or compared. For more than 20 years, for example, the Cancer League campaigned for cancer cases to be recorded nationally on a uniform basis. But no corresponding federal law was enacted until 2020.

Great Britain leads the way

“The decentralised nature of health care here makes it difficult to coordinate both data collection and public health activities on a national basis”, says Nicola Low, a professor of epidemiology and public health at the University of Bern. “We have 26 cantonal health systems. As a result, data is often collected in different ways”. What’s more, public health in Switzerland is not considered part of the health system. This is different in the United Kingdom, for example, where public health is firmly integrated into the National Health Service (NHS). “Over there, public health traditions have a much stronger, more consistent basis”, explains Low. “The anti-poverty and sanitation movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries resulted in a lot of national legislation and triggered investments in public health”.

Founded in 1948, the NHS continues the tradition of social medicine today. It is largely financed with public funds, and pursues the goal of achieving socially equitable health care. Public health plays a central role in this, and is promoted accordingly. According to Low, the training of professionals in the NHS is “very well structured”. Important positions in the health service are filled by the appropriate experts, and uniform systems for collecting, analysing and disseminating data were established early on. Britain’s public health research and practices are considered pioneering on the international scene.

Switzerland, however, scores poorly in an international comparison, according to Antoine Flahault, a professor at the Institute of Global Health at the University of Geneva: “Other countries invest significantly more in the infrastructure that provides the public health system with high-quality epidemiological data”. Denmark, for example, has an excellent information system that collates data on hospitalisations, surgery in cities, the results of additional examinations, deaths and medical prescriptions. In the USA, very good, repeated cross-sectional studies with large samples are carried out. And France has developed a programme for accessing its health-insurance data, making it possible, for example, to combine data on vaccinations for Covid-19 with hospital stays or Covid diagnoses.

“Swiss insurers, by contrast, have little imposed on them when it comes to sharing their data”, says Flahault. Moreover, little is being done to involve the population in research, such as data donation cards or opt-out models. Only in the case of cancer registration has the opt-out solution been in place since 2020.

Switzerland did not always keep public health on the back burner like this. Even in the first third of the 20th century, the relevant structures were being vigorously expanded. Investments were made in the cantonal medical services, a conference of health directors was set up, health leagues were founded, the Swiss Society for Health Care was initiated (today Public Health Switzerland) and chairs of hygiene were created at universities.

As a model, Switzerland looked to the social hygiene approach of Germany, which at the time was a world leader in statistical and social medicine. It was in Germany, for example, that researchers discovered that the vast majority of the population carried the mycobacterium tuberculosis, though it was those in the lower social strata who died most frequently of the disease.

The long shadows of Nazism

In the Third Reich, social hygiene was then instrumentalised by ‘racial hygiene’, which led to a stigma on social hygiene that continues to have an impact to this day. For example, the English term ‘public health’ is used today in German because indigenous equivalent terms, e.g., ‘Volksgesundheit’, have acquired intolerably totalitarian connotations (compound nouns prefixed with ‘Volk-’ having been popular both with the Nazis and subsequently with the communists who ran the former East Germany).

The Nazi trauma undoubtedly put the brakes on the development of public health in Germany, though it was hardly the decisive factor in Switzerland. “After 1945, we were successful in upholding the myth that research in neutral Switzerland had always remained objective and independent”, explains Pascal Germann, a historian at the Institute for the History of Medicine at the University of Bern. “That meant any connections to Nazi ‘racial hygiene’ could be forgotten easily. This act of forgetting was also a deliberate, political act. As a result, Switzerland was under less pressure than other countries to distance itself from racial hygiene after 1945”.

Yet there was a connection, if only an indirect one, according to Flurin Condrau, a medical historian at the University of Zurich: “One significant trend that was accelerated because of the Nazis – though it was hardly a conscious decision on their part – was the rise of the USA as the international centre of medical research instead of Germany. Social hygiene had never been popular in the USA, where there was an early focus on the role of the individual and on market processes. After the war, this new way of thinking also spread from the USA to Switzerland”.

Politics as medicine on a large scale

Those ideas were very well received, because they fitted perfectly into the catalogue of liberal values that would determine Swiss politics during the decades after 1945. What’s more, individual medicine experienced an enormous upswing thanks to advances in diagnostics and therapies. “The euphoria that resulted made people believe that infectious diseases could be conquered – indeed, diseases in general”, explains Brigitte Ruckstuhl, a historian and public health expert. “As a result, health care in hospitals advanced to being the dominant task of the state”.

In the 1970s, however, the international ‘New Public Health’ movement brought an innovative approach to promoting good health, and its ideas caught on in Switzerland too. After a brief heyday in the 1980s – as reflected in drugs policies and the HIV/AIDS prevention programmes – the introduction of market logic to the health system meant that public health quickly lost ground again. “Despite all their complexity, market mechanisms are always focused on the possibility of charging for medical interventions”, says Condrau. “Public health does not fit into this logic. You can’t bill someone for an illness they’ve managed to avoid”.

To put it somewhat bluntly, medicine has made a good living in recent decades from pretending that it has nothing to do with politics. At the same time, politics has pretended to have nothing to do with medicine. Rudolf Virchow, the 19th-century German liberal politician and pioneer of public health, was of a completely different opinion. In 1848, he wrote that “Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing more than medicine on a large scale”.