Debate

Should the identity of peer reviewers be open?

Peer reviews of scholarly articles are still mostly anonymous. Two experts here discuss whether transparency would create greater trust and solve the problems that exist.

Image: zVg

Image: Sarah Wiltschek

Peer review has increasingly come to serve as a signal of the validity, integrity and trustworthiness of research results. I argue that the open identity of peer reviewers can increase trust in the scientific process.

In the early days of open access, a main argument by opponents was: If the authors have to pay to publish an article, then this will encourage journals to review them leniently and publish more inferior articles to increase their income. For new open access journals, it was essential to demonstrate a rigorous peer-review process to counter this argument. They began to do so by naming their peer reviewers. It was a revolutionary tactic – now no one could accuse the journal of not peer reviewing, or of drawing on inexperienced reviewers. Reviewers’ names were proof that a serious review process had taken place, because a researcher’s reputation was on the line. For open access, opening up reviewer identity was a crucial step towards establishing credibility and building trust. This was a lesson that all journals should learn.

Looking to the future, the growing culture of preprints provides clues as to how open identity in peer review may develop. The past 10 years have seen a sharp rise in the number of researchers posting early versions of their work online in this way. They are publicly available and may be shared, discussed, cited and reviewed on a growing number of platforms – from informal tweets to fully fledged review platforms, e.g., PRE Review or ScienceOpen. In open systems, reviewer identity matters, because in academia, expertise and deep knowledge of a field are painstakingly accumulated over years of hard work. It matters whether a comment is by a leading scientist with decades of experience or a young researcher with only tangential knowledge of the field.

Trust in scientists, in the scientific process, and in the truthfulness of the published record in an increasingly global and decentralised world is essential if we are to be successful in tackling the challenges that lie before us. Researchers should step up and sign their reviews.

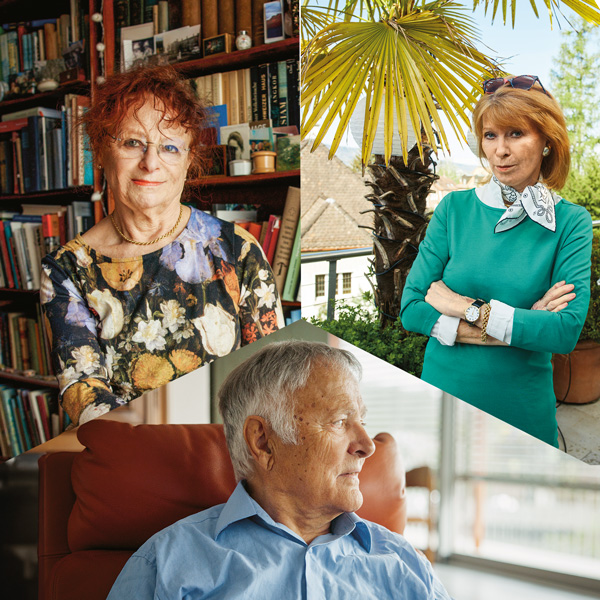

Stephanie Dawson is the CEO of Science Open, a start-up company that provides networks for open-access publishers and researchers and that develops new ideas in scholarly publishing.

Identifying peer reviewers is a poor answer to the wrong question. ‘De-anonymisation’ may promote trust, but does it actually improve the quality of peer reviews? It is rare for reviewers to write malicious or careless reviews, or to submit reviews that are an embarrassment to those who’ve written them. However, reviewers are indeed beholden to numerous, widespread biases. Some of them are scientifically justifiable (e.g., when reviewers are more stringent in their own specialist field), while others are not (e.g., matters of linguistic taste). But these are biases that no reviewer can simply ‘turn off’, regardless of whether or not their identity is disclosed.

You’re actually asking the wrong question, because it links the problems to the responsibilities of individuals. Peer review has long since ceased to be an aristocratic instrument of censorship, which was how it originated (‘peerage’ refers to the English nobility). Peer review has become the procedurally organised infrastructure for assessment that serves to steer modern systems of science and scholarship. The only thing that has remained ‘aristocratic’ is its claim to collegiality: whoever I review favourably today will also review me favourably tomorrow.

However, the criticism that peer reviewers are insufficiently diverse is justified. Remedying this will not happen through transparency, because it depends on money and motivation. Someone will only feel intrinsically motivated to write a peer review if they feel they have a lasting future in science with good working conditions, or if they have the prospect of extrinsic reward in the form of payment or career advancement. It would be easier to engage in the targeted recruitment of marginalised groups.

For the world of scholarship, this would mean not just paying attention to quotas organised according to gender, age or nationality, but also respecting marginalised theories, methodologies, research questions and disciplines that do not meet simplistic criteria of excellence. If there were a sensible use for lotteries in science, then it would be in peer review, where it could promote a randomly chosen, more diverse selection of peer reviewers!

Martin Reinhart is a professor at the Robert K. Merton Center for Science Studies at the Humboldt University in Berlin. He is researching into peer-review procedures and peer review in science.

Image: zVg

Peer review has increasingly come to serve as a signal of the validity, integrity and trustworthiness of research results. I argue that the open identity of peer reviewers can increase trust in the scientific process.

In the early days of open access, a main argument by opponents was: If the authors have to pay to publish an article, then this will encourage journals to review them leniently and publish more inferior articles to increase their income. For new open access journals, it was essential to demonstrate a rigorous peer-review process to counter this argument. They began to do so by naming their peer reviewers. It was a revolutionary tactic – now no one could accuse the journal of not peer reviewing, or of drawing on inexperienced reviewers. Reviewers’ names were proof that a serious review process had taken place, because a researcher’s reputation was on the line. For open access, opening up reviewer identity was a crucial step towards establishing credibility and building trust. This was a lesson that all journals should learn.

Looking to the future, the growing culture of preprints provides clues as to how open identity in peer review may develop. The past 10 years have seen a sharp rise in the number of researchers posting early versions of their work online in this way. They are publicly available and may be shared, discussed, cited and reviewed on a growing number of platforms – from informal tweets to fully fledged review platforms, e.g., PRE Review or ScienceOpen. In open systems, reviewer identity matters, because in academia, expertise and deep knowledge of a field are painstakingly accumulated over years of hard work. It matters whether a comment is by a leading scientist with decades of experience or a young researcher with only tangential knowledge of the field.

Trust in scientists, in the scientific process, and in the truthfulness of the published record in an increasingly global and decentralised world is essential if we are to be successful in tackling the challenges that lie before us. Researchers should step up and sign their reviews.

Stephanie Dawson is the CEO of Science Open, a start-up company that provides networks for open-access publishers and researchers and that develops new ideas in scholarly publishing.

Image: Sarah Wiltschek

Identifying peer reviewers is a poor answer to the wrong question. ‘De-anonymisation’ may promote trust, but does it actually improve the quality of peer reviews? It is rare for reviewers to write malicious or careless reviews, or to submit reviews that are an embarrassment to those who’ve written them. However, reviewers are indeed beholden to numerous, widespread biases. Some of them are scientifically justifiable – e.g., when reviewers are more stringent in their own specialist field – while others are not – e.g., matters of linguistic taste. But these are biases that no reviewer can simply ‘turn off’, regardless of whether or not their identity is disclosed.

You’re actually asking the wrong question, because it links the problems to the responsibilities of individuals. Peer review has long since ceased to be an aristocratic instrument of censorship, which was how it originated (‘peerage’ refers to the English nobility). Peer review has become the procedurally organised infrastructure for assessment that serves to steer modern systems of science and scholarship. The only thing that has remained ‘aristocratic’ is its claim to collegiality: whoever I review favourably today will also review me favourably tomorrow.

However, the criticism that peer reviewers are insufficiently diverse is justified. Remedying this will not happen through transparency, because it depends on money and motivation. Someone will only feel intrinsically motivated to write a peer review if they feel they have a lasting future in science with good working conditions, or if they have the prospect of extrinsic reward in the form of payment or career advancement. It would be easier to engage in the targeted recruitment of marginalised groups.

For the world of scholarship, this would mean not just paying attention to quotas organised according to gender, age or nationality, but also respecting marginalised theories, methodologies, research questions and disciplines that do not meet simplistic criteria of excellence. If there were a sensible use for lotteries in science, then it would be in peer review, where it could promote a randomly chosen, more diverse selection of peer reviewers!

Martin Reinhart is a professor at the Robert K. Merton Center for Science Studies at the Humboldt University in Berlin. He is researching into peer-review procedures and peer review in science.