Portrait

The computer scientist defending our privacy

Carmela Troncoso is a computer scientist who fears that the location data from our cell phones is open to misuse, and she tests technologies for their data-protection efficiency. She describes herself as an introvert, is an activist for LGBT+ rights, and helped to develop the SwissCovid track-and-trace app. We look at how she keeps it all together.

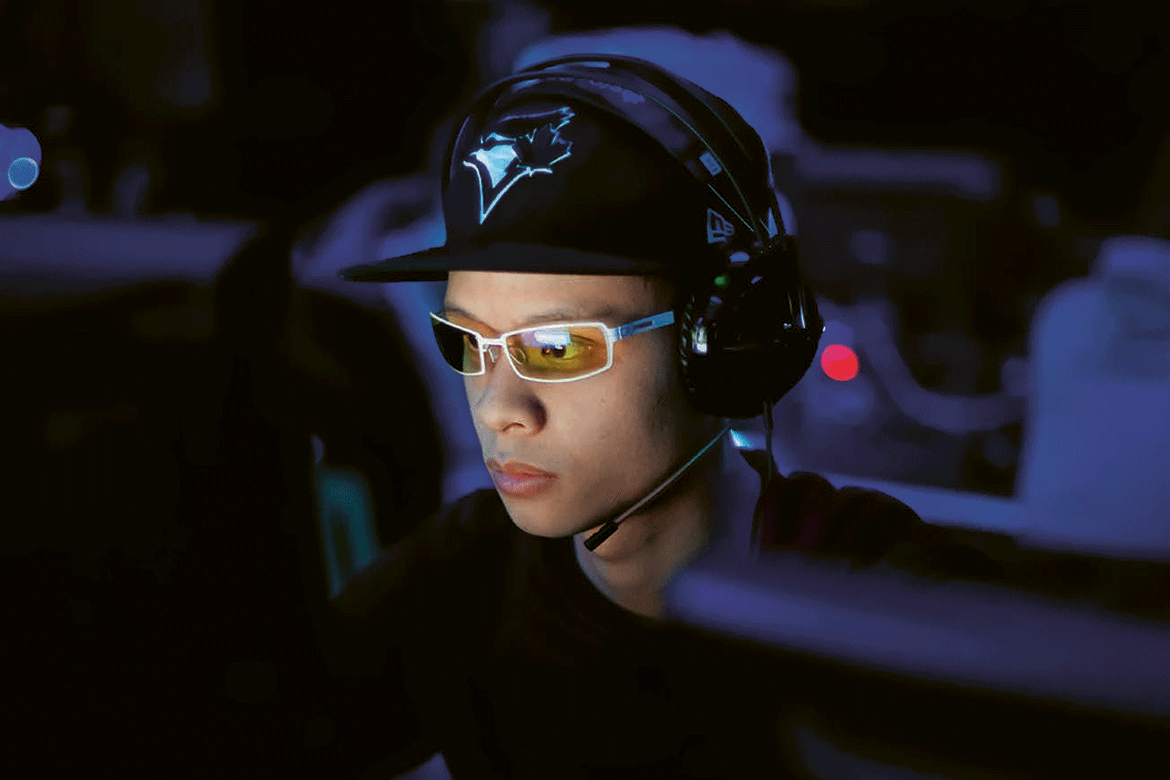

Vaccines are always tested thoroughly – but digital technologies aren’t, says data protection expert Carmela Troncoso. But they, too, can cause massive damage. | Image: Jorge Msanz

Carmela Troncoso does not like to talk about herself unless it is necessary. “I’m a reserved, rather introverted person”, she says. It seems only logical then that she is a researcher heading the laboratory investigating data security and privacy at EPFL.

Troncoso has yet to hit 40 and becomes more talkative when we touch upon her research. “We are developing technologies that allow us to take advantage of the digital world in a socially responsible way and without compromising values that we hold dear”, she says in a video interview from her hometown of Vigo, where she was spending her last weeks of pregnancy. “In the real world, our privacy is protected by the walls and the volume of our voice. We can choose to talk in a café or in a forest, and we don’t necessarily say the same thing to our friends as we do to our parents. But in the connected world, the rules change”.

Delayed digital technologies

Troncoso reminds us that our ‘likes’, our search engine queries and our social network profiles are caught up by the dragnets of Internet giants who collect them and create databases that can be exploited at our expense. She cites the Cambridge Analytica scandal which saw the data of millions of Facebook accounts siphoned off and analysed, then used to influence the way the account holders voted during the 2016 American presidential election.

“We need to slow down and start building digital technologies differently”, says Troncoso. “That’s what we usually do with other technologies: during the Covid-19 pandemic, access to the vaccine was not allowed until it had been properly tested”. The rush to bring digital technologies to market, she says, is because the impact of the loss of privacy is not very tangible. “If a vaccine is unsafe, people die and you can see that, and if a car is unsafe, it causes accidents. With digital technologies, however, the damage is slower and harder to see. But this creates huge problems”.

Troncoso is concerned, for example, that with the current questioning of abortion in the US, geographical data or data from menstrual tracking apps could be used to the detriment of affected women. “It’s not about protecting privacy for privacy’s sake, but because it protects us”.

Troncoso is developing secure working platforms for non-governmental organisations, e.g., ICRC and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. “We are helping the ICRC, for example, to benefit from the advantages of biometrics, but without creating large databases that could be stolen or misappropriated”, she says, recalling that the Taliban seized such virtual documents when they returned to power last year. She is also testing technologies that claim to be privacy-friendly. “There is a lot of ‘privacy washing’”, she says. That is, the use of processes designed to make people think, erroneously, that a company is acting responsibly in terms of privacy protection.

Given Troncoso’s driving passion, it is hard to believe that she embarked on an academic career simply because, after completing her studies in telecommunications, she “didn’t want to have a job, get up early and dress well every morning”. So she undertook a PhD at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, where she became interested in privacy. The rest is now history.

Open LGBT+ activist

Since accepting a position as an assistant professor at EPFL in 2017, however, Troncoso has openly displayed one part of her private life: her homosexuality. “It is important that people in positions of power create role models so that people see that homosexuality exists, that it is normal and that it is not a hindrance in life”. With this in mind, Troncoso has stopped using the term ‘partner’: “I say ‘my wife’ on purpose because I want it to become normal”. She is also working to make the EPFL campus more inclusive, e.g., by organising monthly ‘queer aperitifs’ and by urging the management to replace the overly restrictive ‘paternity’ and ‘maternity’ leave with the term ‘parental leave’.

She reveals that she was formerly a football player but has since turned to alpine hiking. As regards her activism, it also developed in Switzerland, in response to the situation faced here by its LGBT+ community. “I’ve never had to face hostile reactions in the street, it’s more about having rights, which Switzerland makes difficult”, she says. It was precisely so that her wife could also appear as a mother on the birth certificate that the couple decided to move to Spain for the birth of their child.

The young couple intend to return to full-time work after their parental leave, albeit with adjustments to their schedules. They have parallel academic careers: Rebekah Overdorf, Troncoso’s wife, is a specialist in digital forensics and recently took up a position as assistant professor at the University of Lausanne’s Faculty of Law. Overdorf is an American and describes her partner as “very funny and pragmatic” and as a “passionate and altruistic scientist, incredibly intelligent and creative”.

International recognition

Indeed, Troncoso has gained international recognition by developing a decentralised contact tracing system for the SwissCovid application. The system is known as ‘DP-3T’ (Decentralised Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing), it allows contacts to be traced without creating large personal databases, and has been adopted by similar applications around the world.

This achievement led her in November 2020 to be named one of Fortune magazine’s 40 Leaders Under 40 in the technology category. “I found it extremely important that this magazine, which is mainly interested in economic successes, singled out an advance that does not generate money but protects privacy”, she says. She is also pleased to note that, following her outreach to peers in the Swiss National Covid Task Force, the Swiss Parliament held a session on the subject of data power. “For me, this was very important, even more important than the development of the app”, says Troncoso.

One thing is certain: even if Troncoso doesn’t like to talk about herself, that doesn’t mean we won’t still hear more about this activist researcher.