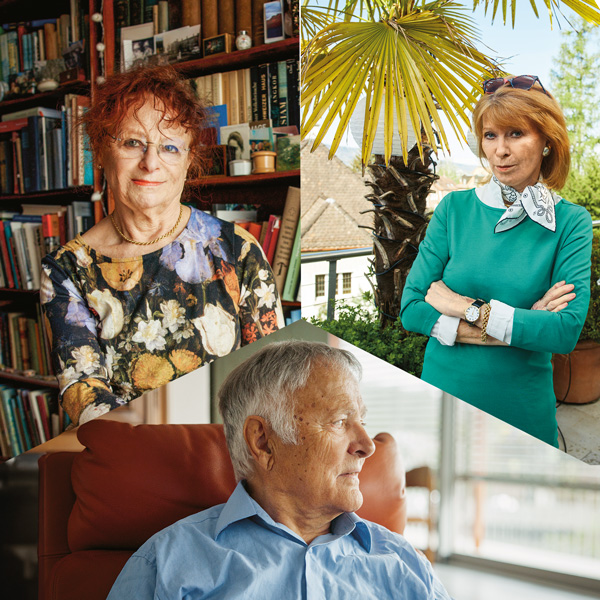

RESEARCH FLAGSHIPS

Charting new worlds or running aground?

After setting sail nearly ten years ago, Europe’s billion-euro flagship programmes have encountered many a stormy sea. But while one programme dedicated to graphene remains very much afloat, another – focused on the human brain – is foundering.

Illustration: Chi Lui Wong

“Our mission is to build a detailed, realistic computer model of the human brain”. Those were the words of Henry Markram, a neuroscientist at EPFL, in a TED conference speech he delivered in 2009. Markram was describing what came to be known as the Human Brain Project (HBP), a hugely ambitious attempt to reproduce the entire workings of the human brain in a supercomputer. The idea was that this would make possible a deeper scientific understanding of this mysterious organ, and that it would help facilitate new treatments for mental disorders. It also raised the possibility of doing away with animal experiments.

This grand vision was to entail very practical consequences, in the form of one billion euros worth of research funding. Markram and his colleagues were awarded the money when the project was chosen by the European Commission in 2013 as a ten-year flagship programme. It was one of two projects to receive this honour, the other being an initiative to harness the immense technological potential of graphene – single layers of carbon atoms that are flexible and that combine great strength with excellent conductivity of both electricity and heat. By bringing together scientists from dozens of institutions across the continent, each of these flagships was designed to achieve long-term goals that would be unattainable through any single national programme.

Now, nearly a decade on, these two flagships are approaching the finishing line – at least, that was the plan. In reality, these initiatives have been on quite different voyages. According to their respective research directors, the graphene initiative is on course to spend the full one billion euros by around 2027 – extending the duration of the programme by four years – while the HBP will have to make do with a reduced total of just over EUR 600 million.

For more information, move your mouse over the illustrations or tap on them.

The differing fortunes of the two programmes are being followed closely by the leaders of two more recently selected flagship initiatives – one in quantum technology and another in batteries. Their current statuses are also reflected in the moods of researchers in the two communities. Graphene scientists appear largely enthusiastic about their programme’s achievements, while many neuroscientists outside the top brass at the HBP have lambasted the project for not having even approached the stated aims. In the words of Kevan Martin, a former co-director of the Institute of Neuroinformatics at the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich, the failure of HBP to simulate a human brain “is plain for all to see”.

Bickering about who’s in charge

The ‘flagship’ concept was launched by the European Commission in late 2009 as part of its Future and Emerging Technologies programme, which is designed to develop novel types of information and communication technology. Numerous projects were proposed, and the Commission announced the winners in 2013. It committed itself to stumping up half of the one billion euros for each of them; the other half was to come from national governments and industry. However, it did not take long for the mood to turn sour.

Just seven months after the HBP was launched, its three-person executive committee decided to ditch cognitive and systems neuroscience from the project. That prompted some 150 neuroscientists to dispatch a letter of protest to the Commission, and led to a mediation process under Wolfgang Marquardt, the chair of the board of the Forschungzentrum Jülich research centre in Germany. The result was the dismantling of the committee and its replacement by the 11 heads of the HBP’s sub-projects.

The project’s current scientific director, Katrin Amunts, also from Jülich, argues that progress since then has been very marked. She maintains that neuroscientists have made a number of discoveries that would not have been possible in the absence of the HBP, e.g., work combining data from different sources allowing the pinpointing of brain regions to be removed during epilepsy surgery. She adds that, through the EBRAINS infrastructure, the programme is providing researchers with remote access to neuroscientific data sets, a brain atlas and simulation tools.

Other neuroscientists, however, are far from convinced. Yves Frégnac of the CNRS in France maintains that EBRAINS will likely be a far cry from the promised database that was supposed to have been the heart of the HBP. This is because it will apparently lack the necessary curated data at multiple scales within the brain. He adds that this typifies what he calls the “economy of promises” that Markram made in trying to sell the virtues of the HBP. To win a flagship competition, he says, “you may have to promise the moon even if you are not going to the moon”.

Making profits in Europe is hard

It’s a rather happier story emerging from the Graphene Flagship. According to its director, Jari Kinaret of Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, for every ten million euros invested, the programme has generated around 150 academic publications and more than 13 patent applications. That’s over ten times as many patents as the Commission’s original target. He admits that it has taken longer than expected to commercialise many of the devices produced in academic laboratories up to now, particularly when it comes to the heavily touted electronics applications. But 15 new companies have so far emerged from the programme, which he considers to be “quite respectable”, even though he does not know whether any have so far turned a profit.

Kinaret’s enthusiasm is shared by others involved with the graphene flagship. Andre Geim of Manchester University in the UK, who shared a Nobel prize for his work on graphene, says that the programme’s research output and the creation of new companies “have exceeded any reasonable expectations”. Andrea Ferrari, the director of the Cambridge Graphene Centre in the UK, also describes the initiative as “overall a resounding success”, although he adds that the volume of paperwork has at times been frustrating.

Despite its success, however, it appears that the European Commission is not keen to replicate the graphene experience. For the next two programmes of this kind (the Quantum Flagship and BATTERY 2030+), it chose not to embark on an open competition of independent proposals. Instead, it chose the subject areas itself and issued calls for projects within them.

According to one of its organisers, Tommaso Calarco of Forschungzentrum Jülich, the Quantum Flagship aims to close the gaps with China and the US. As he points out, both these countries have taken big steps in advancing quantum technology. China has built a 2,000-km-long stretch of quantum-encryptable fibre and launched a quantum communications satellite, while America’s rich high-tech firms, e.g., Google, continue to improve processors for quantum computing. Calarco argues that European scientists do pioneering fundamental research, but not enough to commercialise their results. “European industry is not lacking vision or courage”, he says, “it is just lacking cash”.

To try and make up this shortfall, the European Commission and national governments have of late been throwing ever greater amounts of money at quantum research and development. According to Calarco, the Quantum Flagship’s original one billion euro budget has now risen to a whopping EUR 7.5 billion over its ten-year lifetime, including monies from national programmes. The Commission has multiplied its share of EUR 500 million fourfold, while national governments have collectively raised their stake tenfold – in part by drawing on funds earmarked for post-Covid recovery.

More bottom-up big science?

While the Quantum Flagship is awash with funds and the Graphene Flagship is due to carry on for at least another four years, it seems that other flagship hopefuls will remain empty-handed for the time being at least. Another six contenders, competing for two or three more funding initiatives, had been expecting a final decision in 2020, but were told by the Commission that the new research framework, Horizon Europe, which is running from 2021 to 2027, in the end had no room for any flagships.

For Alexandre Pouget at the University of Geneva, that may be no bad thing. Pouget has been a vocal critic of the HBP, arguing that neuroscience might benefit from relatively small groups of researchers forming spontaneously from the bottom up, rather than the top-down approach typical of flagships. To that end he is working on a EUR 30 million international network of 21 neuroscience labs to coordinate work on a single topic – in this case a complex decision-making task in mice, for which they soon expect to release a brain map.

Pouget argues that neuroscientists need to learn from the collaborative ethos of physicists, including their joint development of powerful tools. While large physics facilities are expensive, he says that their price tag is often justified, pointing out that the LIGO gravitational-wave detector cost around one billion euros, but that physicists would never have observed this previously unseen type of radiation without it. In this spirit, he says he would welcome an independent and transparent audit of the HBP to establish whether or not its research really proves worthwhile. “When you spend that kind of money the results have to be equally spectacular”, he says.