Feature: Cinema, fact and fiction

Playing with the space-time continuum

Science fiction movies love time travel – but there’s little hope of it soon becoming science fact. We take a look at why it continues to fascinate us.

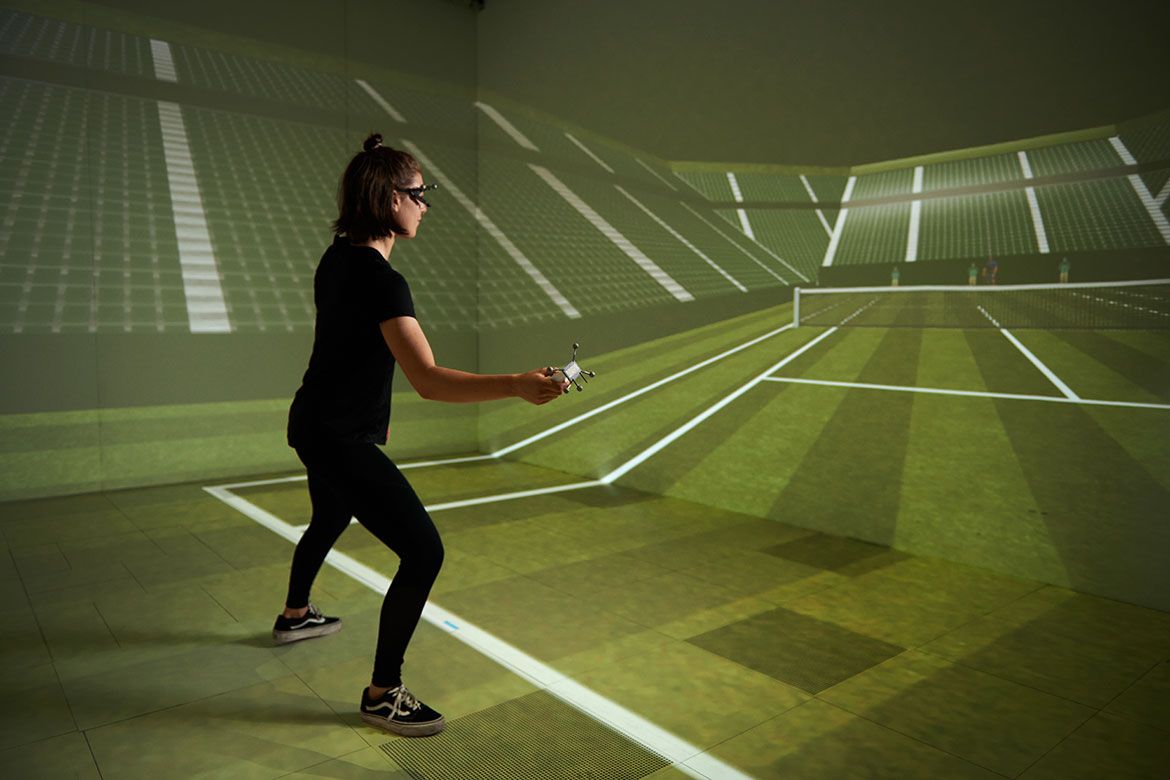

Whether it’s a time machine or just a server room: Everything looks more spectacular in the movies. | Image: Michel Gilgen

Science fiction offers humankind worlds in which everything is theoretically possible – worlds where we can peer into the future, and also adapt our past to make it suit our desires. “We are fascinated by time travel because it allows us to set ourselves free of the limits of space and time”, says Marc Atallah, a senior lecturer in French literature at the University of Lausanne and director of Maison d’Ailleurs, a science-fiction museum in Yverdon-les-Bains.

In fact, all we need to travel in time is to look at the starry sky, where we can gaze millions of years into the past, as far back as light itself needs to travel from distant galaxies to us on Earth. But the effects described by Einstein’s Theory of Relativity mean ‘time travel’ doesn’t have to remain a passive experience on our part. When we move at high speed, or are exposed to strong gravitational forces, time passes more slowly, relative to everything else. In ‘normal’ space travel, however, astronauts only experience such deviations in the range of several millionths of a second over the course of a year.

In the blockbuster movie ‘Interstellar’, by contrast, hours turn into years as a spaceship approaches a black hole on its mission to save humanity. Time stretches out even further in the film ‘The Planet of the Apes’, where astronauts land on an unknown planet that eventually turns out to be their home planet Earth – but far in the future, after it has been devastated by nuclear war.

Actions have consequences

This elasticity of time is one of four categories of time travel described by the physics YouTuber Henry Reich. On his ‘Minute Physics’ channel, he also discusses the motif of the time loop as celebrated in the comedy ‘Groundhog Day’, where a cynical weatherman has to live out the same day over and over again until he reforms his character to such an extent that a work colleague falls in love with him.

Reich also pays special attention to his own favourite example of time travel: the scene in ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban’ where Harry and Hermione travel back three hours in time, but have to observe their earlier selves proceed through events exactly as before. They cannot change the past, which means that no time paradox arises. As Reich explains: “Logical consistency is a primary thing that … I think lays the foundation for good time travel stories – not because logical consistency is important in and of itself, but because, most of the time, in order to care about the characters in a story, we have to believe that actions have consequences”.

The most popular form of time travel, however, is ‘anything goes’. As a rule, time machines are the means of achieving it – like the car with the ‘flux capacitor’ in the film ‘Back to the Future’, which accidentally sends the teenager Marty McFly back from 1985 to 1955. He promptly messes up his parents’ first date, which confronts him with two problems: he has to find his way back to his own time, but first has to ensure his own existence by playing matchmaker to his parents. In the process, he even manages to make them both cooler than they were before.

In theory at least, this kind of time travel could be possible. If you play with the equations of relativity, you can create cross-connections in space-time (that’s the four-dimensional continuum comprising the three dimensions of space plus the dimension of time). These so-called ‘time loops’ could enable you to move forward into the past.

Another possibility that has been a subject of much discussion is wormholes – a kind of tunnel that could connect two different places and different times in the Universe. In the cult BBC series ‘Doctor Who’, one end of a wormhole is located in Cardiff in Wales. Wormholes are theoretically possible in physics, but no one has ever observed one. The warp drive used in the ‘Star Trek’ universe provides for faster-than-light speeds and thus also in principle involves a reversal of time. In order for such a distortion of space-time to be possible, we would somewhere have to discover exotic matter that possesses negative mass.

Epiphanies from the impossible

“There are no reasons for us to believe that time travel will ever be possible”, says Stefan Wolf, the head of the Cryptography and Quantum Information Group at the Università della Svizzera italiana in Lugano and co-author of an article on the topic of time travel. “But nor is there any reason to rule out the possibility of it”. However, no research is being undertaken anywhere into the time travel of particles, he says. “The theoretical investigation of the possibility of time travel opens up a field in which we might study mathematical phenomena, and where we might perhaps find reasons for rejecting the possibility of time travel”.

Marc Atallah believes that it’s precisely because we intuitively know our physical boundaries that we are so interested in tales about this phenomenon: “Time travel enables us to tell interesting stories”, he says. It means we can rethink the past – just like in the sci-fi film ‘Das Jesus Video’, in which the Catholic Church is afraid of the consequences of a video of Jesus made by time travellers. And when we postulate a hypothetical, far-off future, it offers us the necessary critical distance for us to take a hard look at our present times. That happens in the movie ‘The Time Machine’, in which its hero travels from Victorian London to a future when humankind has split into two different species – one that lives below ground and has turned to cannibalism, and one that lives a comfortable life on the Earth’s surface, but has abandoned all intellect. And there are also interesting examples of time-travelling paradoxes, as in ‘12 Monkeys’, at the close of which the main character is shown as a child, witnessing his own murder as an adult. The moral here is: even time travel can’t help you evade your fate.