Dating apps

Love me Tinder

Couples who meet over dating apps actually want to move in together quickly and have children, while highly educated women find it easier to meet less educated men on the Internet. Recent studies into love in an age of online dating are upending common assumptions.

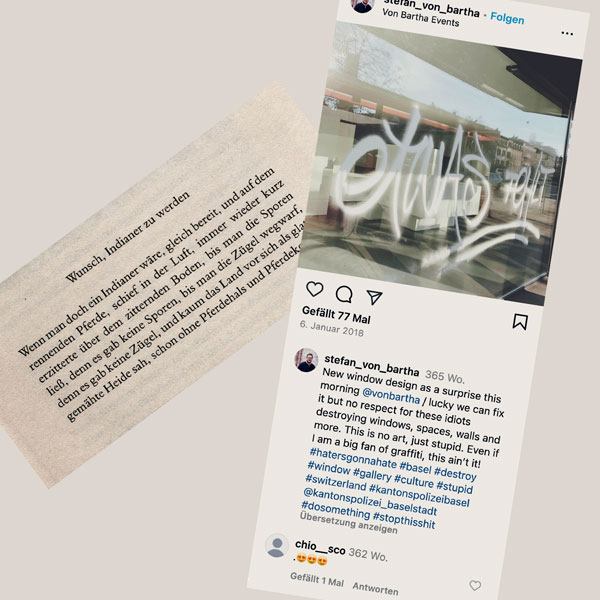

Not always, but ever more often: couples are increasingly engaging in long-term relationships after meeting on Tinder & co. | Image: Nora Dal Cero, from the series ‘(N)irgendwo angekommen’

Internet dating sites were still a niche phenomenon some 10 to 15 years ago. But today, online dating has definitely gone mainstream. Across the world, more than 40 million people use Tinder every month. Those who are critical of today’s trends like to claim that dating apps such as Tinder, Hinge and Bumble are so popular because they are perfectly suited to an age when our ‘relationship culture’ in general is being eroded. They believe that this immense freedom of choice to which we are exposed has deprived people of the will and even the ability to engage in real, lasting relationships. These cultural pessimists often lament that digital dating sites are a ‘vanity fair’ on which self-promotion is paramount, and the primary goal is a selfish one of getting the best deal – whether for just one night or a few months.

Kai Dröge is a sociologist who has reached a more differentiated conclusion in his study of online dating. Together with his colleague Olivier Voirol at the University of Lausanne, he has examined the structures of dating portals and conducted extensive interviews with men and women, some of whom have been searching online for a partner for many years. Dröge and Voirol have found that there are two mutually antagonistic rationales that can be summed up in the concept of the ‘romantic entrepreneur’. This is someone who conducts their search for a partner in a rationalised, strategic manner, in line with notions of mass consumption; but they are also seeking intimacy, emotion and the magic of fate.

Intimacy becomes routine

Surprisingly, the Internet does not seem to prove any obstacle to developing romantic feelings. On the contrary: it can actually fire them up. Dröge was “surprised by how quickly people open up to each other on the Internet, telling highly personal, intimate things about themselves, and how quickly this can result in feelings of deep familiarity and closeness”.

He has several explanations for this. “Paradoxically, it can make online relationships all the more intense and personal, precisely because there is a sense that they are fleeting. You are largely anonymous and can break off contact immediately”. What’s more, our bodies are “strangely absent at the outset, with conversation taking centre stage instead”. People get to know each other “from the inside out”. The online medium also offers a lot of space for our imagination.

Disappointment is therefore often all the greater when people have their first encounter in physical space. “We did not conduct a single interview in which people didn’t tell us about such disappointing experiences”, says Dröge. An obvious solution to this would be for people to meet sooner and thereby bring forward the moment of decision. Apps like Tinder promote this. Long chats are frowned upon there, and the goal is a swift physical encounter. And if one such meeting doesn’t work out, then the next date is often already waiting. Many users chat simultaneously with several potential matches – sometimes even dozens of them. “But such a multiplication of contacts and an acceleration in encounters has its own problematic side-effects”, says Dröge. “People’s messages become repetitive, they tell each other the same stories over and over again, they know how to gain the trust of their potential match, how to build up intimacy and to generate emotions in themselves and others. But this takes our experience of intimacy as a very special experience, shared with only a few people in life, and transforms it into a pattern that is frozen in routine”.

Yearning for a future

And yet many people do find each other online. According to a study conducted by the University of Geneva, every fourth couple that came together in Switzerland in 2017 and 2018 met online. Every tenth couple met on a dating app. Gina Potarca heads this research project on how the Internet is influencing contemporary relationships.

Contrary to the alarmist scenarios that we often hear about, she found that ‘online’ couples do not shy away from long-term commitment. “Our interviews showed that these couples are just as likely to want to marry in the near future as are offline couples. In fact, they are even keener to start living together, and show a greater desire to have children”.

This desire to move in together is probably so intense – says Potarca – because couples who meet on the Internet often live further apart and want to ‘check out’ their relationship. As for their greater desire to have children, Potarca believes that single people who are keen to become parents in fact prefer dating apps as a way to find a partner.

Potarca also found that online dating seems to promote social mixing to some extent – which in itself is astonishing. Internet dating allows for more frequent relationships between highly educated women and less educated men. She suspects that this has to do with the selection methods employed, which on the Internet are focused mainly on the visual aspect. She also believes that women can find a larger pool of potential candidates online. Offline spaces for interaction are more segregated, which means that these two specific groups are less likely to meet. It is also the case that there are no outsiders to interfere when they establish contact online – neither a ‘best friend’ nor a daughter, nor colleagues at work.

Preselection by algorithm

So are dating apps really the great motor for liberation that is being touted by the technological ideologues? According to them, online relationships conform to our romantic ideals because we can establish them as we want, without any social control from outside. But they remain silent about the fact that algorithms are helping to determine with whom we can begin a relationship in the first place. Jessica Pidoux is a sociologist who investigated just such hidden mechanisms in her doctoral thesis at EPFL.

On Tinder, for example, the selection of potential matches is controlled by algorithms that are coded according to our gender and socioeconomic status, and also utilise data including our online behaviour. The Tinder app learns by analysing our online actions and preferences; these are then subjected to a process of generalisation and hierarchisation. In many cases, according to Pidoux, it reinforces racist, patriarchal models. She offers an example: if many older, well-educated men like the profiles of younger women with a low level of education, then the algorithm will suggest older, wealthy men to younger women.

Pidoux is also certain that social mixing is not necessarily promoted, just because our initial decision on Tinder and co. is based on a photo. At least, this isn’t the case with everyone. “Who is suggested to whom depends primarily on the composition and behaviour of the majority of the app’s users. If that majority comprises white, heterosexual, well-educated people, then these will be far more visible on the app. For them, it will be easier to find partners across all categories, while those from other categories will be less visible, rarely ‘liked’, and will tend to stay with their own community”.

Potarca admits that dating apps “don’t completely fix” either our prejudices or more conservative ways of choosing a partner. But she says that they do open up more possibilities compared to traditional ways of finding someone. “Both my study and research in the USA have shown that apps promote social mixing across educational levels. In the USA, you can also observe a strong impact on intercultural mixing”. This effect has not been observed in Switzerland. Potarca believes that this is because people with a migration background are strongly underrepresented on Swiss dating apps. When they want to hook up with someone online, they tend to prefer dating websites and social networks.