Report

Rising from the heat and dust

On the Sirkeli Mound in southern Turkey, past millennia are being revealed – one ceramic piece after another. We join a Bernese archaeological expedition into antiquity.

These young researchers work every day in the searing summer heat of southern Turkey, piecing together the puzzles posed by the excavation at Sirkeli Höyük. They are making their way through 20 different layers of ancient history. | Photo: Özge Sebzeci

Just as the sun is rising, a group of 28 Swiss and Turkish archaeologists arrive on a village bus. In the crisp morning air they start climbing hills containing settlements that date back many centuries. Their goal is an 80-acre patch of land on the Sirkeli Mound in the province of Adana in south-eastern Turkey. To one side of it runs the Ceyhan River, on the other lies a historic castle of the Armenian Kingdom in the Misis Mountains.

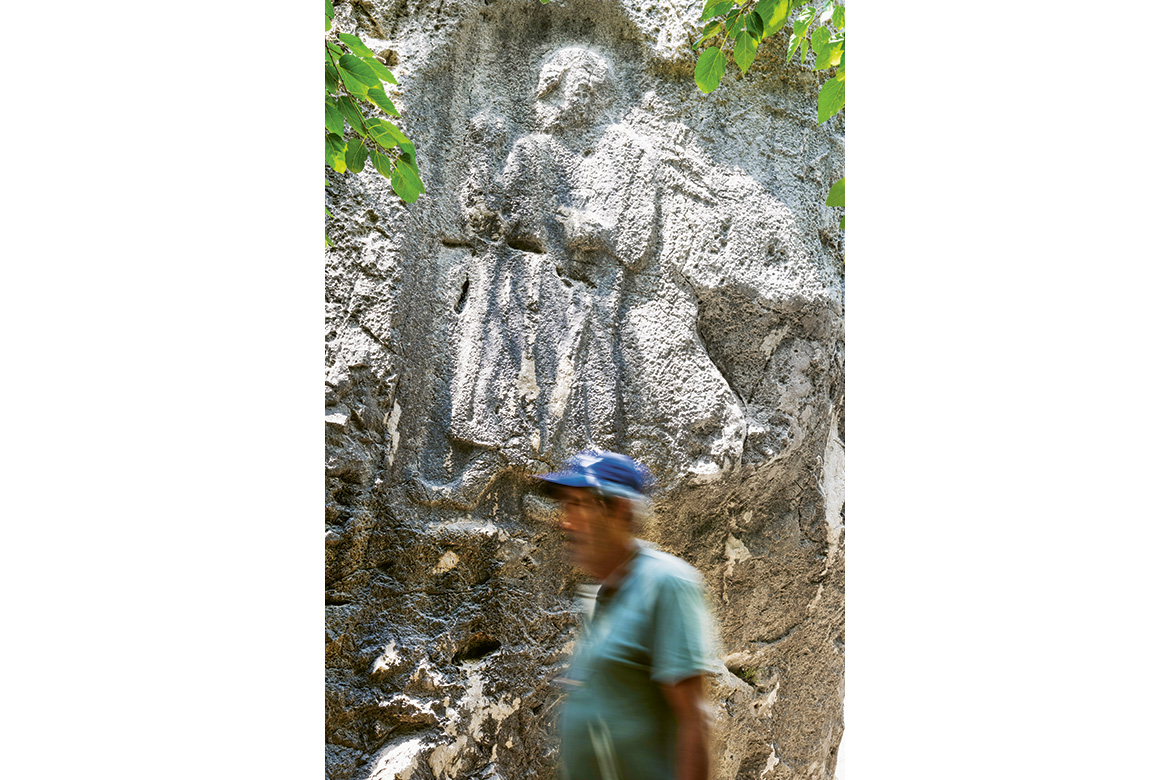

Everywhere they tread contains deep layers of ancient history. This region was once known as Cilicia and is today situated in southern Anatolia in Turkey. It was first inhabited in the Neolithic Period, then was home to Hittite, Hellenistic, Roman, Armenian and Islamic civilisations. Sirkeli is a multi-period site – meaning that one city was built here on top of another. The earliest Hittite rock relief in Anatolia was discovered to the north-east of the Sirkeli Mound.

It commemorates a major victory for the Hittite leader Muwattali II (1290-1272 BCE) in his war against Ramesses II, one of the best-known pharaohs of the Egyptian New Kingdom. Muwattali II is depicted with one of his hands lifted, as if praying, while his other hand holds a long, curved stick. These two men fought one of the most famous battles of the Bronze Age. It took place at the Syrian city of Qadesh, near the present-day city of Homs.

The archaeological dig at Sirkeli has two co-leaders, Mirko Novák and Deniz Yaşin-Meier, both of whom are from Bern University, which has been sending teams here since 2011. “We are interested in all periods, but of course you have to deal with the latest periods at the beginning”, says Novák. “So the focus in the first years of our work was the Iron Age, including Neo-Hittite and Aramaean cultures, Phoenicians, and the Neo-Assyrian Empire, who all left their traces here in Cilicia”. Now, in many places, they have reached the Middle Bronze Age layers of civilisation, according to the chronology of the ancient near East. This means that their focus is slowly shifting to around 1900 BCE. “The main powers then included Babylon, Assur and Aleppo, to name just three”, he says.

A railway laboratory

The first dig here was organised by an English team back in 1936. Today, funding comes solely from Swiss sources. Novák says that Bern University is keen to add to our understanding of the cultural history of Cilicia. In particular, his team is studying “the development of towns in all these periods, and changes in ceramics as an indicator of cultural identities”. At some point in the future, he hopes to put on an exhibition in Bern with all their findings. Sirkeli is the largest mound in the region, and the only one where both ancient settlements and rock reliefs are found side by side. According to one of the co-leaders Deniz Yaşin Meier, other prominent Cilician mounds have been encircled by modern housing developments, limiting the amount of research that can be done there.

There are currently four active dig sites at Sirkeli. They regularly turn up 4,000-year-old ceramics and other household items. Buckets of stones and ceramic pieces are taken every day to be dusted and washed in a research centre located in a revamped former station of the Baghdad Railway line. The most significant pieces are labelled and placed into specific categories. This is dusty, laborious work, but the team is excited about its findings. Julien Rösselet is a recent graduate from Bern who’s working here alongside his girlfriend Joëlle Heim, a PhD student who is researching into the architecture of Sirkeli and Cilicia. As the morning progresses, temperatures rise and Rösselet tells us it will become almost “unbearably humid” here. He wears an Indiana Jones-style hat because he feels “better protected” when wearing it.

Siestas and ice lollies

Excavation work only takes place in the summer months because the researchers have academic projects that take place in the winter. At breakfast – three hours after the team arrives – the archaeologists are already discussing their first findings of the day. Then they head off again into the scorching sun, all wearing baseball caps or turbans to protect their heads. Rösselet motivates himself to continue by thinking of the “cool time” in his hammock after lunch, when he and the rest of the team will take a siesta. Some of the men and women, he says, make ice lollies to help them survive the heat.

Rösselet is particularly excited by a find he made last year: a terracotta figurine depicting a standing woman. It dates back to the Iron Age and is closely related to Assyrian and Babylonian models. Since then, his find has been showcased by the museum in the city. Protected by his large straw hat, he spends each day at one of the digs, piecing together what he finds as he makes his way through twenty consecutive layers of history. At one o’clock in the afternoon, the sound of a train bell and a high-pitched horn summon the team for their lunch break. Sitting underneath aged mulberry trees, they eat alongside four historic wooden train carriages from the Baghdad Railway that are almost a century old.

There are other challenges besides the piercing heat. Since these Swiss academics are working on Turkish land, they have to undergo a detailed application process for work permits just like any other foreign researcher. Astonishingly, it takes half a year just to sort out the bureaucracy for each annual dig. Then there is the tight budget under which the team is operating. The dig is paid for solely by Swiss research, with no funding from Turkish sources that could have expanded their capacity here by making it a joint venture. So there are limits on what tools they can buy, the number of days they can spend in the field, and the number of workers they can hire.

Despite the limits of their funding, everything possible is done when it comes to scientific analysis. Thanks to Bern University, the team has access to cutting-edge, reasonably priced Carbon-14 dating technology to analyse the age of items such as seeds. With the right equipment and seeds, it is possible to date a piece back 10,000 years. Frustratingly, however, a recent change in Turkish law, ordered directly by the President, means that ancient seeds cannot be removed from the country for research purposes. Instead, the Swiss team has to find local laboratories within the city borders. This limits the devices and technology on offer, and eats into their budget.

After their lunch break, the whole team withdraws for a siesta lasting a couple of hours until four p.m. Later, everyone will work with the ceramics experts to sort their findings before the sun sets. Archaeologists also draw whatever pieces have been discovered that day before documenting them and organising them into different categories. Evenings are spent in a simple house in the village of Sirkeli, just a few yards away from the Mound, where they all sleep.

The team has meanwhile been totally accepted by the community. One of the villagers, Ömer Bayer, says that during his childhood he was not allowed to get close to the Muwattali relief and surrounding rocks. His family had ordered him to keep away, calling the relief – which is carved on dark rocks – a “black witch”. Bayer is grateful that the archaeologists have told everyone in his village the truth about the rock relief and the Hittite leader that it portrays.

Destroyed by quarrying

Sadly, the Mound and its surroundings have not always enjoyed protection. There are quarrying sites just three kilometres away, and some of the homes in Bayer’s village have been destroyed by the shockwaves from dynamite explosions conducted there. “There is no longer any activity in the nearest quarries”, says Yaşin-Meier, “but we know that many remains of historic civilisations have been bulldozed. We can see from our own old satellite images that there was once a large plateau that was spacious enough for homes, temples and other buildings. These have been destroyed, which is a real pity”.

Despite being thousands of kilometres away for much of the year, the Swiss/Turkish team continues its essential work throughout all the seasons. In the winter, they organise a ‘Café Fixe’, a weekly meeting in their university canteen in Bern to coordinate the Sirkeli project in between their digs.