Grasslands

The foggy, foggy dew

Dew and fog can be essential for the survival of our pastures and meadows because they still provide water, even in dry periods. We take a look at the big impact of tiny water droplets.

Misty alps in Canton Fribourg: an idyll also enjoyed by plants, because it means they take in water. | Image: Anne Gabriel-Jürgens / 13PHOTO

Autumn mists: In our imagination, we automatically associate this seemingly mystical weather phenomenon with this season. But in fact, mists are especially important in the summer. Because when the fields are dry, every drop of water is precious. It is only recently, however, that the impact of fog and dew on our meadows has begun to be studied properly in Switzerland. “Research into this has so far concentrated mainly on the dry regions of the Earth”, says Andreas Riedl.

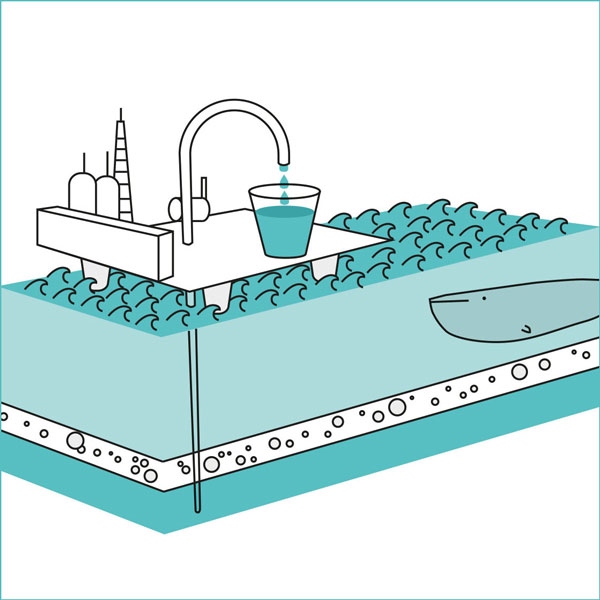

It was during Riedl’s doctoral studies at ETH Zurich that he discovered that an average of 140 millilitres of water per square metre can accumulate each night, even when it doesn’t rain. “That doesn’t sound like much”, he admits. After all, even a light rain shower can bring many times that amount of water down from the clouds. “But since fog and dew can occur frequently, even small amounts can have a major impact on plants”.

What’s more, the tiny droplets in fog and dew wet the entire surface of leaves, which means that they can absorb the water especially well. At one measuring station in the canton of Zug, Riedl was able to observe 127 such events in one year, with dew occurring much more frequently than fog. So it is primarily dew that brings water.

Alpine grass suffers the most

This regular micro-dosage of water will probably become even more relevant in Switzerland in the future. As our climate heats up, there is an increased probability of longer dry periods that can be fatal to meadows and pastures and that will also have major implications for our agriculture. Three-quarters of agricultural land in this country comprise grassland. According to Agroscope, large-scale droughts – such as already occurred in the years 2003, 2006, 2015, 2018 and 2022 – result in production losses of up to 40 percent. And meadows don’t just provide animal fodder. They are also biodiversity hotspots. For example, 100 square metres of dry grassland can contain up to 100 different plant species.

Dew could ensure the survival of grasslands in hot seasons. “It has the advantage that it also forms in the summer and during dry periods”, says Riedl. This is because warmer air can store a lot of water that then condenses on the plants during cool, clear nights, providing moisture. Even fog can occur in dry summers.

Swiss grasslands are suffering from the impact of global warming, especially at high altitudes in the Alps, where a third of Switzerland’s meadows are to be found. Researchers at the University of Basel have shown that alpine meadows take much longer to recover from drought stress. Their growing season is in any case short, and the seeding of the grasses becomes more difficult.

One man went to weigh a meadow

Outdoor experiments have helped Riedl to achieve a better understanding of the special behaviour of these tiny water droplets. “We discovered, for example, that the microclimate is much more important than other factors, such as the altitude”. This is because the wind is one of the natural enemies of dew and fog – along with insufficient humidity – and meadows in mountainous regions are often located on highly exposed slopes.

But in order to be able to measure these tiny amounts of water as accurately as possible, Riedl first had to develop the necessary instruments himself. To this end, three large clods of meadow were placed in a kind of oversized flowerpot on an extremely precise set of scales and examined at eight different locations from 393 to 1,978 metres above sea level. Evaporation made the pots lighter, while dew and fog made them heavier. This allowed Riedl to measure the amount of water absorbed. Additional sensors detected whether fog was present. This enabled the research team to determine the source of the microprecipitation.